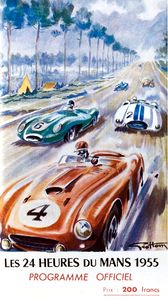

1955 24 Hours of Le Mans (partially found footage of World Sports Car Championship race; 1955)

This article has been tagged as NSFL due to its discussion of a fatal motor racing accident/disturbing visuals.

The Mercedes driven by Pierre Levegh goes airborne after having clipped Lance Macklin's Austin-Healey.

Status: Partially Found

The 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans was the fourth round of the 1955 World Sports Car Championship Season. Occurring from 11th-12th June 1955 at the Circuit de la Sarthe, the race would ultimately be won by Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb in a Jaguar D-Type. The race would also be partially televised live on the Eurovision Network. However, the event is most remembered for featuring the deadliest accident in motor racing history, which claimed the lives of Mercedes-Benz driver Pierre Levegh and 83 spectators.

Background

The 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 23rd running of the event, forming part of the 1955 World Sportscar Championship Season.[1][2] The event is not only the most prestigious race in endurance racing that is still run annually as of the present day, it is also classified as part of the Triple Crown of Motorsport, alongside the Monaco Grand Prix and the Indianapolis 500.[3]

From a television standpoint, the 1955 edition was the second to be televised live.[4][5] Under the direction of Jean d'Arcy, ten RTF cameras and three outside broadcasting vans were placed throughout the 13km circuit, while six relays were built between Le Mans and Paris to transmit the signal and respective commentaries from French and international journalists.[4][5] Here, the signal would be received in countries within the fledging Eurovision Network that sought to provide pan-European broadcasts.[4] Among those receiving the signal included France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.[4] In total, twelve broadcasts occurred throughout the event's duration, with a total of five hours being transmitted live.[4] It was also RTF's first significantly large live broadcast of a sporting event.[4]

Prelude to the Race

Heading into the event, three teams were seeking to gain victory within the S-5000 / S-3000 class, typically known as the "Grand Prix Formule Libre" cars.[6][7][8] Defending race winners Ferrari entered the 735 LM, and hedged its bets somewhat by splitting its three driver sets based on experience.[6] Meanwhile, Jaguar entered D-Types with enhanced engine power and consequently top speed, opting to place 1953 winners Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton, as well as Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb, within two of its three works cars.[6] Finally, Mercedes-Benz re-entered the event after last making the 1952 edition, with 300 SLRs containing air brakes; considering the German manufacturer's dominance of other motorsport categories like Formula One, Mercedes were considered the favourites to win the race.[9][6][8] Their main challenger consisted of eventual 1955 Formula One World Champion Juan Manuel Fangio and runners-up Stirling Moss, while Pierre Levegh would race with John Fitch in one of the remaining two cars.[6][8] In total, 70 vehicles were entered to compete within the various classes, including Lance Macklin privately entering alongside Les Leston in an Austin-Healey 100 S.[10][6][7] 60 competed in the race itself.[6][7][8]

During practice, the Ferraris, Jaguars, and Mercedes were all proving competitive enough to easily break the track's lap record.[6] Ferrari's Eugenio Castellotti set the fastest time of 4:14, a second ahead of Fangio. Early signs of safety concerns arose when three separate accidents occurred that resulted in serious injuries to Gordini teammates Jean Behra and Élie Bayol.[11][6] Behra was waiting within the pits, which were unguarded and situated directly next to the race line.[6] As Moss was exiting the pits, DB-Panhard's Claude Storez approached at speed and rear-ended the Mercedes, Moss only carrying on with slight damage as he already partially accelerated away.[6] However, the DB bounced into the path of Behra, trapping him and injuring his leg.[6] Meanwhile, Bayol suffered a fractured skull and broken vertebrae when he was forced to take evasive action upon encountering two spectators crossing the track ahead, rolling his car in the process.[11] Despite the serious accidents raising questions surrounding driver and spectator safety, the race would commence as planned.[6][11]

The Race

The race itself commenced on 11th June at around 4pm.[6] Castellotti made the strongest start, leading from the initial few bends, with Hawthorn making it through to second.[12][6] While Fangio's start was delayed as his one of his trouser legs got caught on the gear lever, he nevertheless proved competitive enough to reach fourth by lap 3, and by the first 30 minutes he was chasing Hawthorn for second.[13][6][12] Despite his strong start, Castellotti was unable to fend off Hawthorn and Fangio; thus the race's early stages consisted of a three-way duel for first.[6] By around 4:50 pm, Fangio had passed Hawthorn, only for the Brit to overtake the Argentine five minutes later.[6] The pair according to Motor Sport had seemingly forgotten about the endurance side of Le Mans, setting numerous lap records in an attempt to outpace each other.[6][12][13] Fangio notably broke the lap record five times, while Hawthorn did so in three instance, an average speed of 123 mph being set in the process.[12] Eventually, Castellotti's engine began to deteriorate, allowing Hawthorn and Fangio by after 15 laps.[12][6] At 6pm, the pair continually overtook one another, and were often separated by just two seconds per lap, while Castellotti was now a minute behind in third.[6]

At 6:26, Hawthorn and Fangio started lap 35, with the former opting to make a pit stop.[14][6][12] As he did so, Hawthorn inadvertently triggered Levegh's fatal accident.[14][12][6][13][7] As police and officials dealt with the crash's aftermath, another occurred at the Maison Blanch corner.[6] MG's Dick Jacobs lost control not long after exiting the corner, causing his MG to roll over, land inverted, and become ablaze.[6][7] Jacobs suffered serious injuries as a result.[6] During the night, Moss and Bueb took over at Mercedes and Jaguar respectively, while Castellotti's Ferrari retired as a cylinder block had split.[6][12][7] By 1:40 am, Moss was well-ahead of Bueb.[12][6] However, he and the other remaining Mercedes would withdraw out of respect for those who perished in the crash.[12][6][13][7] Other teams like Gordini would also withdraw before the race's conclusion.[11]

With Moss and Fangio out, Hawthorn and Bueb dominated the remaining stages of the event.[6][12][8] Despite facing constant rain for the remaining four hours, the Jaguar would win after completing 307 laps, also setting a record speed in the process.[6][12][7] An Aston Martin DB3S driven by Peter Collins and Paul Frère finished second and was the best performing S 3.0-class vehicle.[7] A second Jaguar D-Type driven by Jacques Swaters and Johnny Claes took third.[7] Further down, a Porsche 550 RS Spyder driven by Helmut Polensky and Richard von Frankenberg was highest-placed 1.5; a Bristol 450C entered by Peter Wilson and Jim Mayers was the best-performing 2.0; the highest-placed 1.1 was a Porsche 550 RS Spyder driven by Auguste Veuillet and Zora Arkus-Duntov; while Louis Cornet and Robert Mougin drove a DB HBR-MC to 16th, the best-placed 750.[7]

The Deadliest Crash in Motor Racing History

On lap 35, Hawthorn was narrowly leading Fangio.[14][9][12][13] Prior to the pit straight, he had encountered and lapped Mercedes driver Pierre Levegh for the first time, as well as Austin-Healey's Lance Macklin in the fourth instance.[14][9] Not long after lapping Macklin, Hawthorn realised he needed to pit as instructed by his team a lap earlier.[12][14][9] He therefore veered towards the pits, and to ensure he reached his spot, braked harshly.[12][14][9] However, he did these actions right ahead of Macklin, who was forced to take evasive action to avoid a collision since his drum brakes were less powerful than the Jaguar's.[9][14][12][10] As Macklin darted to the right and slowed, Levegh was driving at 150 mph and had nowhere to go.[9][14][12][10] Thus, in his final act, he warned the approaching Fangio about the disaster, which saved the Argentine's life.[12] In contrast, the Frenchman rear-ended the Healey, causing his Mercedes to go airborne, before crashing into an embankment and erupting into flames.[9][14][12] Levegh was thrown free from the car, and was killed instantly upon landing, aged 49.[15][9][14][12] A motorsports veteran, Levegh was also known for his skating, and as a world-class ice hockey and tennis player.[15] He had come close to winning the 1952 24 Hours of Le Mans, and had also been concerned about the rising speeds of the cars heading into the 1955 edition.[12][9] Meanwhile, Lance Macklin spun and collided with the opposite wall, though he escaped shaken but unharmed.[12]

The Mercedes itself disintegrated and exploded.[14][9][12] Hot debris, including the engine, the rear hood, and the air brake, suddenly turned into high-speed projectiles that tore through the spectator stands before anyone had a chance to react.[9][14][12] Many spectators were killed by the debris, with dozens decapitated by the rear hood alone.[9][14][12] Others would perish in the explosion and resulting fire, made worse by the car's burning magnesium that sent embers into the crowd.[9][14] Firefighters on-scene worsened the fire, as pouring water on magnesium only helped ignite it further, causing the flames to burn for hours.[9] In total, 83 were dead, and a further 120 injured, in what is deemed the worst accident in motor racing history.[14][9][12][15] Despite the accident's heavy death toll, the organisers decided to continue with the racing, primarily out of concern that ending the race prematurely would block the roads and prevent emergency vehicles from reaching casualties.[12][14][9] Mercedes would withdraw from the event hours later, mostly out of respect for the dead, but also due to concern winning the race would now be a PR disaster for the German manufacturer.[14][12][9] Other teams like Gordini withdrew, but despite requests for the Jaguar team to do the same, its team leader Lofty England declined.[14][11]

Following the race's conclusion, some like the French magazine L’Auto Journal and Macklin blamed Hawthorn for the accident for cutting ahead of Macklin and braking too hard.[14] While the Brit was reportedly upset and guilt-ridden immediately following the incident, a photo of him smiling post-race was used by the magazine as a smear, its headline stating "To your health, Mr Hawthorn."[14] However, Hawthorn supporters believed Macklin and Levegh were not competent enough for the high-speed race, increasing the likelihood of a fatal accident.[14] Ultimately, the official inquiry deemed no driver was at fault, and instead criticised the track for being unprepared for the increasingly quick cars.[14][10] The Circuit de la Sarthe was constructed in 1923 for cars that had a top speed of 60 mph.[14] With only limited changes since its inception, the inquiry believed the track, particularly its unguarded pit lane, was unsafe for vehicles that now had triple the top speed of the cars of the 1920s.[14]

Thus, the track experienced multiple safety improvements, including the destruction of the original pit straight stand.[14] Elsewhere, several countries banned motor racing temporarily, although Switzerland has yet to legalise circuit racing as of the present day.[9][14] Meanwhile, Mercedes, who were already withdrawing from motor racing from 1955 onwards to concentrate on its road cars, would not make a return to motorsport until 1987.[16][9][14]

Availability

Various footage of the race was captured, primarily from amateur and newsreel sources.[17] Additionally, it is known that an RTF camera captured one of the few videos of the accident itself.[5] However, the Eurovision broadcast itself has yet to resurface, having originated from an era where telerecordings were rare until videotape was perfected in the late-1950s.[18] Nevertheless, some RTF footage was included in a French newsreel.[17]

Gallery

Videos

Images

See Also

- Peter Dumbreck's 1999 24 Hours Of Le Mans crash (lost on-board footage of LMGTP accident; 1999)

- Sébastien Enjolras (lost footage of fatal 24 Hours of Le Mans pre-qualifying accident; 1997)

References

- ↑ Ultimate Car Page listing the various 24 Hours of Le Mans held since 1923. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ Motor Sport detailing the 1955 World Sportscar Championship Season schedule. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ The Amalgam Collection detailing the race's prestige and noting its presence as part of the Triple Crown of Motorsport. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Dictionnaire de la télévision française detailing how the event was partially televised live on the Eurovision Network (book in French). Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Journaliseme Sportif noting RTF cameras were present at the event, with one capturing footage of the accident (book in French). Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 Motor Sport providing a detailed race report. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Experience Le Mans detailing the results of the event. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 24h-Le Mans summarising key facts of the race. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 The New York Times detailing the Mercedes 300 SLR and the disaster. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Austin-Healey detailing Macklin entering the event, and him being involved in the fatal accident. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Amedee Gordini detailing Bayol's accident and summarising Levegh's fatal accident. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 12.24 12.25 12.26 12.27 Sports Illustrated detailing the race and the disaster. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 24-Le Mans summarising Fangio's and Moss' performance in the race. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 14.18 14.19 14.20 14.21 14.22 14.23 14.24 14.25 14.26 GQ Magazine documenting the disaster. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Motorsport Memorial page for Pierre Levegh, also noting the spectators who perished in the accident. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ Silver Arrows detailing Mercedes' withdrawal from motor racing, and its eventual return. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 INA providing a French newsreel of the event, with images filmed by RTF. Retrieved 15th Sep '22

- ↑ Web Archive article discussing how most early television is missing due to a lack of directly recording television. Retrieved 15th Sep '22