Formula One (partially found footage of Grand Prix races featuring fatal and/or serious accidents; 1958-1978)

This article has been tagged as NSFL due to its discussion of fatal and serious motor racing accidents/disturbing visuals.

Since its inception in 1950, Formula One has hosted numerous Grand Prix that have featured fatal and/or serious accidents. This article documents such races, which are confirmed to have received live or tape-delayed television coverage but have since become lost media. It should be noted that although the events' television broadcasts are lost, it does not necessarily mean the accident footage is missing as well.

1958 French Grand Prix

The 1958 French Grand Prix was the sixth race of the 1958 Formula One Season. Occurring on 6th July at the Circuit de Reims, the race was ultimately won by Ferrari's Mike Hawthorn, his last Formula One World Championship victory. The event also marked an end of an era, as it was five-time champion Juan Manuel Fangio's final Formula One race, with future champion Phil Hill making his debut. However, the race is also infamous for the fatal accident of Ferrari driver Luigi Musso.

It was the eighth running of the event in the Formula One calendar,[1] with the race lasting 50 laps.[2] The 37th French Grand Prix overall,[1] the race has been held at a variety of circuits, with the last one held at Reims occurring in 1966.[3] After the race was dropped from the schedule in 2009, it returned in 2018, being held at the Circuit Paul Ricard.[3][1]

Heading into the race, Ferrari had high confidence of success following a suspension change to its 246s.[4][5] The team was ecstatic when Hawthorn achieved pole position with a time of 2:21.7, which also set a Reims lap record.[6][4][5][2] Directly behind him was teammate Musso, with BRM's Harry Schell lining up third.[4][2][6][5] In contrast, Vanwall was struggling with overheating cars, with star drivers Tony Brooks and Stirling Moss only qualifying fifth and sixth respectively.[5][4][2] Meanwhile, Fangio competed in a new works Maserati, but faced disappointment,[4][5] qualifying eighth out of 21 competitors, though he had seemingly grown tired of driving an underpowered Maserati against up and coming drivers and cars.[6][5][2] Future champion Phil Hill made his World Championship debut in a Maserati, qualifying 13th on the grid.[5][4][2] Unlike with previous races, the field also appeared to contain a balance of green (British) and red (Italian) cars.[4]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1958 French Grand Prix commenced on 6th July.[2] Schell beat Hawthorn and Musso at the start, but Hawthorn managed to regain it prior to the back straight.[4][5][6][2] Schell then lost multiple places a lap later, with Ferrari's Peter Collins making it a 1-3.[4][5] However, he then lost a metal air-scoop situated above the Ferrari's magneto, which ended up behind the brake pedal.[4] He was forced to remove it on the escape road, dropping him to the back of the field.[4][5] Hawthorn controlled proceedings, and began to lap cars after 10 laps.[4][6] Suddenly, Musso suffered his fatal accident, promoting Brooks to second.[4][5][6][2] He did not remain there, as two laps later, he entered the pits with a failing gearbox, retiring on lap 16.[4][5][2] The race for second, therefore, began to emerge between Moss, Fangio, and BRM's Jean Behra.[4][6]

On lap 25, Fangio dropped out of contention to resolve gearbox issues, dropping to sixth behind Ferrari's Wolfgang von Trips and the recovering Collins.[4] He was unable to make ground due to the sheer pace of those ahead, but did move up to fifth when Behra retired on lap 40 following a fuel pump failure.[4][5][6][2] Moss was well-ahead in second, but simply could not challenge Hawthorn, who set a lap record on lap 45.[4][5][2] Hawthorn, therefore, claimed his first victory in four years, and eight points in the Drivers' Championship, with him, awarded another for the fastest lap.[4][6][5][2] Moss finished second, with von Trips taking third.[2][6][4] Collins ran out of fuel on the final lap, allowing Fangio to move into fourth despite spinning on the same lap.[4][5][6][2] This proved to be the five-time champion's final Formula One race, with Hawthorn refusing to lap the Argentine so he could complete the full race distance.[6][4][5][2] Collins pushed his car over for fifth, with Hill finishing a clean race in seventh.[4][6][2]

The result left Hawthorn level on points with Moss in the Drivers' Championship, with this also marking the Brit's final victory in the sport.[7][6][4] But despite Hawthorn's win and Fangio's last race being marked, no ceremony would occur as news spread of Musso's death.[6][4] Post-race, Fangio stated "I stopped the car in the pits and a decision was made. I would stop racing. But there was no ceremony for me and no joy for Hawthorn. I then went to the hospital to see poor Musso. But poor Musso was gone."[6]

Death of Luigi Musso

On lap 10, Musso was running in second behind Hawthorn.[8][4][5] According to Musso's girlfriend Fiamma Breschi, Musso was involved in an intra-team rivalry with Brits Hawthorn and Collins.[8] The latter pair worked together in races, as they agreed to split their winnings equally, essentially creating a two-vs-one duel with the Italian.[8] Breschi revealed Musso was running into debt heading into the race, and considering that the French Grand Prix then boasted the largest prize pot of all Formula One Grand Prix, he was seemingly placing vital importance on winning the event.[8]

Musso was only around fifty metres behind Hawthorn heading into lap 9, and in the following lap, they began to lap backmarkers.[8][4][6][5] As they approached the Courbe du Calvaire, Musso hit an inside kerb at around 150 mph.[8][5][4] According to Fangio, Musso did not give himself enough room for the corner, causing the Ferrari's front wheel to hit the kerb.[6][4][8][5] It caused the Ferrari to flip into a ditch and roll three times into a wheat field, with Musso being thrown free of the vehicle.[5][8][6][4] Musso's skull was fractured on impact; while he was airlifted to hospital by helicopter, a safety feature recently unveiled, Musso passed away from his injuries, aged 33.[8][6][5][4] The winner of the 1956 Argentine Grand Prix, Musso also achieved ten-second places in his career and was considered a "courageous and brave driver" according to Motor Sport.[8][4]

1958 Moroccan Grand Prix

The 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix was the 11th and final race of the 1958 Formula One Season. Occurring on 19th October at the Ain-Diab Circuit, the race would ultimately be won by Vanwall's Stirling Moss in controlling fashion. However, Moss' title rival Mike Hawthorn finished second in a Ferrari in his final race before retiring from Formula One, which was enough for the latter to become Britain's first World Champion over Moss by one point. The race is also infamous for the fatal accident of Vanwall's Stuart Lewis-Evans, which contributed to Vanwall's withdrawal from Formula One.

It was the first, and to date, only instance of the event being held as part of the Formula One World Championship.[9] Previously, 12 Moroccan Grand Prix were held, with the 1958 edition also marking the last time it occurred.[10][9] The Ain-Diab Circuit had previously hosted the 1957 edition that was won by Maserati's Jean Behra, but the track would be closed following the 1958 race.[11] The race marked the first time a World Championship event had been held in Africa.[12] Heading into the race, Hawthorn led the Drivers' Championship with 40 points, eight ahead of Moss.[12] To become champion, Moss needed to not only win and post the fastest lap but also have Hawthorn finish third or lower.[12][10] Meanwhile, Vanwall had already won the Constructors' Championship in the previous event, leading Ferrari 46 to 40.[10]

When Hawthorn arrived at the event, his mood darkened somewhat when he discovered his Ferrari had the number 2 painted on it, which had been used by teammates Luigi Musso and Peter Collins when they suffered their fatal accidents at the French and German Grand Prix respectively.[12] Perhaps to avoid fate, Hawthorn would swap numbers with Olivier Gendebien.[12] In qualifying, the speeds of the Vanwalls and Ferraris were clear, with Vanwall's Tony Brooks already breaking the fastest lap set the previous year, with Hawthorn a tenth of a second behind.[13] Moss initially had trouble setting a fast time, including when BRM's Harry Schell partially blocked him during one of his hot laps.[13] The next day, Moss again suffered issues when his Vanwall's engine failed, taking Brooks' car as the latter had yet to arrive on the circuit.[13] When he did, he took Stuart Lewis-Evans' car, while Lewis-Evans was forced to make do with the spare car.[13] Despite Moss setting faster times in his replacement car, it was Hawthorn who won the pole position, with a time of 2:23.1.[14][13][12][10][9] Moss was second, and happy with this due to the fact he could start his Vanwall at the centre of the front row.[13][12][14][10][9] Lewis-Evans meanwhile would start third out of 25 competitors.[12][13][14][9]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix commenced on 19th October.[14] Moss and Ferrari's Phil Hill made the best starts and were side-by-side when the reached the pits, Hawthorn languishing in third and Lewis-Evans also losing a few places despite a strong start.[13][12][9][14] Hill continued to pressure Moss, but out-braked himself and ended up an escape road, dropping down to fourth.[13][12] With Hill no longer challenging, Moss began to increase the gap between himself and Hawthorn.[12][13][9][14] Hill, however, would eventually re-pass Hawthorn for second by lap 8, but encountered the F2 Cooper-Climax cars that Moss had already lapped, thus being unable to close the gap between himself and the Vanwall.[13][9] Despite Hill setting a lap record of 2:23.3, Moss was now ten seconds in front by lap 13, while Brooks began to challenge Hawthorn for third, passing him on lap 17.[13] Moss suffered a setback on lap 18 however, when he collided with lapped Maserati driver Wolfgang Seidel, taking out the Maserati while damaging his Vanwall's nose.[13][14] Nevertheless, he continued his strong pace, setting the fastest lap and leading Hill by 20 seconds.[13][9]

On lap 26, Hawthorn passed Brooks, only for the latter to regain it two laps later.[13][12] However, Ferrari had been planning for this, tasking Hill to pressurise Moss while Hawthorn could steadily maintain third.[12][13][10] The aim was to try and force a breakdown, considering the cars' general unreliability back then.[12] This worked when on lap 30, Brooks pushed too hard and suffered an engine failure.[12][13][10][14] With Lewis-Evans considerably behind, Ferrari could now allow Hill to end his pursuit of Moss, and enable Hawthorn to pass him for second.[13][12][10][9][14] The overtake occurred on lap 39, whereas it now stood, Hawthorn would become the World Champion.[13][9] With Moss around 71 seconds in front, he now required Lewis-Evans, who was in fifth, to close the gap and challenge the Ferraris.[13][12] However, Lewis-Evans would suffer his fatal accident on lap 42.[12][13][10][9][14]

Thus, despite Moss continuing to increase the gap over Hawthorn, easily winning and earning nine points in the process, it was the Ferrari driver who became the first World Champion in the end, by one point.[13][12][10][9][14] Hill finished third, with the BRMs of Jo Bonnier and Schell claiming the final points positions of fourth and fifth respectively.[13][14] This would mark Hawthorn's final Formula One event; while he stated that he wanted to go out on top, it is speculated that the death of close friend Collins had also contributed to his retirement.[12][10][9] On 22nd January 1959, Hawthorn would pass away in a road accident, aged 29.[15][10][9]

Death of Stuart Lewis-Evans

On lap 30, the event had already witnessed a major accident involving Gendebien, and the Cooper-Climaxes of Tommy Bridger and François Picard on the Brickyard Corner.[16] This resulting accident saw Gendebien and Picard suffer serious injuries.[16] 12 laps later, Stuart Lewis-Evans was running in fifth and was required by Vanwall to close the gap so as to challenge the Ferraris and ensure Moss could become champion.[12][13][10][16] Suddenly his Vanwall's engine expired, and worse its rear wheels locked, causing the car to spin off the road, somersault, and crash into trees.[17][12][13][10] The Vanwall suffered a ruptured fuel pipe which ignited and caused severe burns to Lewis-Evans.[10][12][13][17] The driver was able to escape the inferno but was forced to shield his face and moved away from marshals and firefighters that could have otherwise assisted him.[10][17][12][13]

Vanwall owner Tony Vandervell immediately flew Lewis-Evans to the Queen Victoria Hospital, where he recovered from shock.[17][12] However, the 75% burns he suffered proved too great and he passed away six days later from blood poisoning aged 29.[17][12][10][13] Having started 16 World Championship events, Lewis-Evans finished third twice, at the 1958 Belgian and Portuguese Grand Prix.[16] His small stature yet admirable personality led to him being regarded as "The Little Man with the Big Heart".[16] His fatal accident would have far-reaching consequences for Formula One's future. Firstly, with himself already having suffered from declining health, Vandervell elected to withdraw his team from Formula One out of grief.[10][12][16] Additionally, future Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone, who was close friends with Lewis-Evans, also left the sport until 1965.[10]

1960 Dutch Grand Prix

The 1960 Dutch Grand Prix was the fourth race of the 1960 Formula One World Championship. Occurring on 6th June at the Zandvoort Circuit, the race would ultimately be won by Jack Brabham in a Cooper-Climax, where a duel between him and Lotus-Climax's Stirling Moss was decided by a granite square. The race also marked the debut of future two-time World Champion Jim Clark. However, the event is also infamous for the death of fan Piet Aalder, who was hit by BRM's Dan Gurney in an accident triggered when the BRM suffered a brakes failure.

It was the sixth running of the event within the Formula One calendar, as well as the eighth in Grand Prix history.[18] Lasting 75 laps,[19][18] the race ran on a frequent basis until being dropped from the Formula One schedule following financial difficulties in 1986.[18] Nevertheless, both the track and event would make a return to Formula One from 2021 onwards.[20]

Heading into the race, the works Lotus team needed to draft in a replacement, as John Surtees left for motorcycle racing in the Isle of Man.[21] Thus, the team brought in Jim Clark, in what marked his first World Championship event.[22][21] For qualifying, the Grand Prix's organisers attempted to make two changes to the format: Only the top 15 fastest would be allowed to compete, with the starting order decided by combining each drivers' three fastest times.[21] However, the entrants complained, forcing the organisers to revert to the original format with 20 drivers being allowed to compete.[21] The entrants also wanted guarantees that everyone would receive starting money, but the organisers held firm that only the top 15 would receive it.[21]

In qualifying, Stirling Moss was consistently the fastest in a Rob Walker-owned Lotus, with Brabham and works Lotus-Climax driver Innes Ireland being his only rivals.[21] Moss achieved pole position with a time of 1:33.2, ahead of Brabham and Ireland in second and third respectively.[23][21][19] Gurney started sixth, Drivers' Championship leader Bruce McLaren took ninth in a Cooper-Climax, while Clark would start 11th out of 21 competitors.[19][23] Moss was also given permission by Reg Parnell to drive the new Aston Martin; unlike with his Lotus, Moss was unhappy with this rather uncompetitive machine.[21] Both the Aston Martin and Scarab teams, alongside Cooper-Maserati's Masten Gregory, would withdraw prior to the race start following a dispute over receiving no prize money due to qualifying at the back of the grid.[21][23][19]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix commenced on 6th June.[19] Brabham made a strong start, passing Moss with Ireland facing challenges from teammate Alan Stacey.[21][22][23][19] Further back, Ferrari's Phil Hill also made a remarkable start, as he moved up to the top six after only qualifying in tenth.[21][23][19] By lap 3, Brabham was slightly ahead of Moss, while the two Lotuses continually overtook each other.[21][23] McLaren retired after eight laps following a transmission failure, and two laps later Brabham and Moss were now 17 seconds ahead of the duelling Ireland and Stacey.[21][22][23][19] Gurney was now in fifth, but would then experienced a brakes failure and suffer the accident on lap 11 that claimed Aalder's life.[22][21][23][19] On lap 17, Moss was still right behind Brabham.[21][22][23] However, his race would change when the Cooper drove over a large granite square that had already separated into two pieces.[21][22][23] As Brabham drove over it, his Cooper's rear wheel redirected the granite at the Lotus, bursting one of Moss' front tyres and smashing the wheel rim.[21][22][23] Moss was forced to pit, and would be two laps down from Brabham by the time his mechanics were finished with the pit stop, made worse when a jack was initially unable to get under the car's front suspension.[21][22][23]

Brabham was now 27 seconds ahead of Ireland and Stacey, with Moss down in 12th.[21][22][23] Future champions Clark and BRM's Graham Hill duelled for fourth.[21][22][23] Clark initially overtook Hill on lap 29, but made a mistake at the hairpin that enabled the BRM to re-pass the Lotus.[21][22][23] This occurred again a lap later, and Clark was then forced to drop back as his transmission was failing, eventually retiring on lap 43.[21][22][23][19] With drivers retiring and with him setting a new lap record, Moss had recovered to sixth.[21][22] On lap 58, Stacey retired following a transmission failure, solidifying Ireland's second place and promoting Hill to third.[21][22][19] Moss meanwhile overtook Ferrari's Wolfgang von Trips for fourth, though was now 46 seconds behind Hill.[21][22][23] Elsewhere, Brabham claimed victory and eight points in the Drivers' Championship, finally kickstarting his season after failing to score in the previous races.[22][21][23][19] Ireland finished second, while Hill took third despite Moss' comeback that saw him set a lap record of 1:33.8.[21][22][23][19] This marked Ireland and Hill's first podiums in the World Championship.[24] Von Trips and teammate Richie Ginther claimed the final points positions of fifth and sixth respectively, albeit a lap down from Brabham.[23][19][21]

Death of Piet Aalder

On lap 11, Gurney was running in fifth in his BRM.[22][23][21] As he reached the Tarzan hairpin, a pipe connected to the BRM's rear brakes failed.[21][22][23] Hence, when Gurney braked for the hairpin, the front wheels locked up and caused the BRM to spin out of control.[21][22][23][24] Gurney crashed into the sand dunes, with him being thrown free from the car that ended up lying inverted after it somersaulted through some small fences.[25][21][22][23] While Gurney escaped with only minor wounds, his BRM hit a group of young men situated in a prohibited area, including Piet Aalder.[22][25][23][21] While the other men recovered from their injuries, Aalder was not so lucky.[25][22] He ultimately passed away from his injuries aged 18.[22][23][25][24]

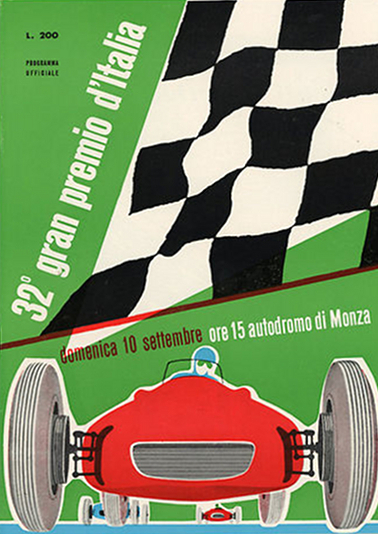

1961 Italian Grand Prix

The 1961 Italian Grand Prix was the seventh race of the 1961 Formula One Season. Occurring on 10th September at the Monza Circuit, the race would ultimately be won by Ferrari's Phil Hill, helping him claim his sole Drivers' Championship and become the first American to do so. However, the race is infamous for featuring the deadliest accident in Formula One history, which claimed the lives of Hill's teammate Wolfgang von Trips and 15 spectators.

It was the 11th running of the event as part of the Formula One calendar, with the race lasting 43 laps.[26] The 31st edition in Grand Prix history,[27] the Italian Grand Prix has been held at Monza for all bar one instance in 1980 since Formula One's inception in 1950,[28] and has garnered a reputation for being the "home" Grand Prix of Ferrari.[29]

The event would also marked the final instance of the Grand Prix utilising the full 6.2 mile version of the Monza Circuit and its banked section.[30][31][32][33] The British teams were unhappy racing at the 6.2 mile circuit, because they deemed the banked track too dangerous for racing, with the teams even boycotting the 1960 edition in protest.[30][31][33] This time, the British teams would compete as engines had been reduced to 1.5 litres, though they again voiced concerns regarding safety and expressed the desire to race on the road circuit.[30][31][33] The race organisers provided a partial compromise by reducing the distance from 50 to 43 laps.[33] Heading into the race, von Trips led Hill in the Drivers' Championship, with 33 points compared to 29.[34][33] The German therefore had the opportunity to secure the title at the event.[33] Lotus-Climax's Stirling Moss was in third with 21 points, and needed to win both the remaining races to stand any chance of winning the title.[32][33][34] Ferrari was also nearing its first Constructors' title prior to the event, with only Lotus having an outside chance of snatching the crown.[33][32][34] Additionally, the team would field a car for Ricardo Rodriguez, making his debut in the World Championship at only 19, despite Hill's concerns about his inexperience, stating "If he lives, I'll be surprised."[35][33][30][32][31]

Ferrari had gained an advantage for qualifying, as the team had conducted extensive testing back in August at the track.[30] All its cars posted times under 2:50, with von Trips achieving pole position with a time of 2:46.3.[30][32][31][26] A tenth behind in second was Rodriguez; by qualifying for the event at 19 years and 208 days, he became the youngest driver to start a World Championship event until the 2009 Hungarian Grand Prix, when Toro Rosso-Ferrari's Jaime Alguersuari qualified for the event at 19 years and 125 days.[35][32][30][33][26] His second place meant he also became the youngest to qualify for the front row, which lasted until the 2016 Belgian Grand Prix when Red Bull-Renault's Max Verstappen achieved the accolade at 18.[36] Ferrari's Richie Ginther and Hill ensured Ferrari had a 1-2-3-4 start, with BRM's Graham Hill starting fifth.[30][33][32][31][26] Moss qualified 11th out of 34 competitors, with the Rob Walker team having swapped their Lotus-Climax with a new V8 engine with a works Lotus four-cylinder originally driven by Innes Ireland.[33][30][26]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1961 Italian Grand Prix commenced on 10th September.[26] Ginther and Lotus-Climax's Jim Clark made the strongest starts, with both battling for the lead ahead of Hill, Rodriguez, and von Trips, who made a poor start.[30][32][31][33][26] However, by the completion of lap 1, Hill had moved into the lead, with Clark dropping down to fifth after being passed by Rodriguez and von Trips.[33][30][32] He then duelled with von Trips, only for the pair to collide on the approach to Parabolica, causing the latter's fatal accident.[37][33][30][31][32][26] Giancarlo Baghetti in a privateer Ferrari, Cooper-Climax's Jack Brabham, and Porsche's Dan Gurney barely avoided the accident ahead.[30][37] Moss meanwhile moved into sixth but was struggling with handling and gearbox characteristics of the works Lotus.[30] As the race progressed, only Brabham kept up with the four Ferraris, with Hill and Ginther occasionally swapping the lead, Hill primarily being ahead.[30][33][26] However, Brabham retired on lap 9 after a water leak convinced him that retiring would preserve the Climax engine.[30][33][32][26]

The Ferraris were now 20 seconds ahead of Moss, who was duelling with Gurney.[30][32][31] However, Rodriguez retired after 13 laps following a fuel pump issue, with Baghetti also being eliminated on the same lap due to an engine failure.[30][31][33][32][26] This convinced Hill and Ginther that while a 1-2 was likely, reducing the pace would ensure their cars would make it to the end.[30] By lap 22, Moss was still ahead of Gurney, with both under 20 seconds behind the two Americans.[30][31] Just two laps later, Ginther became the latest Ferrari retirement, following an engine failure.[30][31][33][32][26] Now that Moss had dealt with the Porsche, he was now motivated to try and close the gap to Hill to keep his title chances alive.[30] However, Hill capitalised on having a new Ferrari engine by increasing the gap to 28 seconds.[30] Suddenly, Moss began to slow, firstly being overtaken by Gurney, before retiring on lap 37 as the left front-wheel bearing overheated and jammed.[31][30][33][32][26]

Thus, Hill claimed victory and with it eight points in the Drivers' Championship.[30][31][32][33][26] This moved him one point ahead of von Trips in the standings; with von Trips now deceased and with Moss unable to catch the American, it assured Hill would be the 1961 Formula One World Champion.[38][30][33][31][32] He became the first American to win the title, the other being Lotus-Ford's Mario Andretti in 1978.[39][31] However, the death of von Trips meant that celebration was muted overall.[33][30][31][32] Gurney was over 30 seconds behind in second, while Cooper-Climax's Bruce McLaren took third.[30][32][26] There was a close battle for fourth, with Cooper-Climax's Jack Lewis and BRM's Tony Brooks finishing together almost in a dead heat; it was later declared Lewis beat Brooks for fourth.[30][32][26] Cooper-Climax's Roy Salvadori would finish a lap down in sixth.[32][30][26]

The Deadliest Accident in Formula One History

On the opening lap, Lotus-Climax's Gerry Ashmore was approaching the Parabolica, but misjudged his speed, causing him to hit the outside grass bank and collide into the forest near the South Banking.[30][33] Ashmore survived, but suffered serious head injuries.[31][33] Despite the serious accident, racing continued.[31][33] The following lap, Clark was racing von Trips in a battle for fourth.[33][30] Halfway through the lap, Clark attempted an overtake, when von Trips moved across to the left-hand side of the track where the Scot was present.[33][30][31][37] The cars collided at around 140mph, with Clark having spun on the track before resting on the grass verge.[40][31][33][37] While he was shaken, the Scot survived unhurt.[33][31][32][37][40] He stated to reporters afterwards "Von Trips and I had been passing and re-passing each other. As we approached the bend, he was almost level with me on my right. He suddenly pulled right across in front of me, and although I had two wheels on the verge, a front wheel touched his rear wheel. What happened then, I don't know."[33][31][37] Brabham, who witnessed the collision, denied allegations that either driver was carving each other up leading up to the accident.[33]

Meanwhile, von Trips' Ferrari somersaulted, before proceeding to mount a banking where spectators were present.[33][37][31][40] Protected only by a chain fence, several spectators were hit by the Ferrari, which then flipped backed onto its wheels and onto the track, with Baghetti, Brabham, and Gurney narrowly avoiding the wrecked vehicle.[33][37][31][40] During the crash, von Trips was thrown free from his car, resulting in him breaking his neck.[41][33][37][31] He was taken to hospital but was pronounced dead aged 33.[33][37][31] A German Count, von Trips was considered a natural motor racing talent, who although was prone to crashing in his early years of racing, would later be given the nickname "Taffy", presumably by 1958 World Champion Mike Hawthorn, with it being a Welsh slang word meaning a brave and fearless man.[41][37][33] He had the opportunity to gain the title at the event, but also expressed concerns about mortality to journalist Robert Daley a day before the race, telling him "It could happen tomorrow. That's the thing about this business. You never know."[33]

Aside from von Trips, eleven spectators were killed instantly in the accident.[37][40][33] A further four would perish in hospital in the following days, therefore bringing the final spectator death toll to fifteen, with many others injured.[37][40][33] To date, it is the deadliest accident to have occurred within Formula One's history.[37][33][40][31][32] As it was among a set of fatal accidents involving spectators that occurred between 1953 to 1961, it led to more demands for the banning of motorsport, while others were concerned that spectator safety was impossible without moving them too far away from the action.[33] Nevertheless, spectator safety has been enhanced significantly at Parabolica, with a double-height debris fence shielding the crowd.[33] Meanwhile, Ferrari, having secured both titles at the race, withdrew from the United States Grand Prix out of respect for the deceased.[33][31]

1962 Monaco Grand Prix

The 1962 Monaco Grand Prix was the second race of the 1962 Formula One Season. Occurring on 3rd June at the Circuit de Monaco, the race was ultimately won by Cooper-Climax's Bruce McLaren, capitalising when BRM's Graham Hill suffered an engine failure and withstanding late pressure from Ferrari's Phil Hill. However, the event is also infamous for an opening lap crash which claimed the life of marshal Ange Baldoni.

It was the ninth running of the event as part of Formula One following its debut on the calendar in 1950.[42] It was also the 20th in Grand Prix history.[43][42] Lasting 100 laps,[44] the Monaco Grand Prix remains an integral event of the Formula One calendar, including being prestigious enough to be classified as part of the Triple Crown of Motorsport, alongside the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Indianapolis 500.[42][45]

Heading into the race, Monaco's race organisers again restricted entry to 16 cars.[46] Ten entries, consisting of the two top drivers from BRM, Cooper, Ferrari, Lotus, and Porsche, qualified automatically, with the remaining drivers battling for the six remaining places.[46] Porsche initially considering withdrawing from the event after finding its cars' performances at the 1962 Dutch Grand Prix disappointing but decided to compete after encouraging results in prior non-championship races.[46]

In qualifying, Graham Hill was generally setting fast times, despite teammate Richie Ginther seemingly struggling with the new BRM's throttle.[46] Motor Sport attributed this to Hill having larger feet than his American teammate, and could engage in better throttle control.[46] Meanwhile, Lotus were rather preoccupied with conducting a film, with numerous film and television crew members occupying its pits.[46] It is also known that French television broadcaster ORTF were eager to film Hill setting a lap time, with Hill complied with.[46] It appeared Lotus-Climax's Jim Clark was frustrated with the constant presence of filming, and so went out to set another time.[46] It proved to be good enough for pole position, Clark setting a time of 1:35.4.[47][48][46][44] Hill would start second, while McLaren qualified third.[46][44] Among the drivers that failed to make the 16-car grid included Jo Siffert, who was eliminated despite out-performing Ginther and other drivers in an outdated Lotus-Climax.[46][44]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix commenced on 3rd June with the track considerably damp.[46][48][44] Flagbearer Louis Chiron made an error by dropping the flag three seconds before the race was due to begin.[46] This caused confusion because jumping the start would result in a 60-second penalty.[46] Only Ferrari's Willy Mairesse started immediately, bumping into the slow-starting Clark and Hill on-route to taking the lead.[46][48] However, Mairesse over sped into the first corner, causing him to slide out of control.[46][48] Clark was forced to stop to avoid a collision, while McLaren and Hill passed through the gaps on each side of the Ferrari to take first and second respectively.[46][48][44] But the sharp braking up front caused havoc behind, with Ginter colliding with Maurice Trintignant's Lotus-Climax, the latter then spinning Lotus-Climax's Innes Ireland.[49][48][47][46] According to Ginther, he was convinced the BRM's throttle had jammed.[48][46]

All three drivers smashed into the wall and strawbales, with one of Ginther's rear wheels colliding with Dan Gurney's Porsche and breaking the rear of its gearbox.[46][47][48] Trevor Taylor's Lotus-Climax was also involved, damaging the car's nose.[46][47] Ginther, Gurney, and Trintignant were all out, while Ireland needed to pit to fix a petrol pipe.[46][47][48][44] During the accident, one of Ginther's wheels detached and hit marshal Ange Baldoni, causing him to suffer serious head injuries.[49][46][47] He was taken to hospital but died from his injuries on 12th June aged 52.[49][47][46] Baldoni was the Automobile Club’s commissaire-contrôleur, and the assistant manager of the Monaco Bus Company depot.[49] The drivers involved escaped uninjured.[47]

McLaren led from Graham and Phil Hill, but the BRM driver began to close the gap, eventually passing the Cooper on lap 7.[46][47][48][44] Hill expanded the gap to McLaren by three seconds after ten laps, as Phil Hill also began to challenge the Cooper driver.[46] However, he spun two laps later, enabling Lotus-Climax's Jack Brabham and Clark to move by.[46][48] Clark passed Brabham for third on lap 22, and now set his sights on McLaren, who was not bothering attempting to challenge Hill for the lead.[46][48] Clark then passed McLaren on lap 27 and set a string of fastest laps.[46][47] Hill countered by setting a lap record on lap 42, but Clark was now just a second behind the BRM.[46][48] Hill however gained breathing space after lapping Lola-Climax's John Surtees and Ferrari's Lorenzo Bandini, with Clark unable to immediately do the same due to Monaco's tight turns.[46] Gear-changing issues meant Clark dropped back to 15 seconds behind Hill by lap 52.[46] He eventually retired four laps later due to a clutch failure, promoting McLaren to second and third respectively, with Phil Hill not far behind.[46][47][48][44]

Graham Hill now led by around 45-48 seconds, but decided to slow down as his BRM's engine began to smoke.[46][48] This reduced the gap to about 36 seconds.[46] Meanwhile, Phil Hill passed Brabham for third on lap 76; a lap later, the Australian spun out, breaking his Lotus' front suspension.[46][48][44] Graham continued to lose time ahead of McLaren, the latter reducing the gap to 26 seconds by lap 90.[46] Meanwhile, Ferrari gave Phil the "flat-out" signal, leading to him maximising his car's performance.[46] On lap 93, Graham retired as the engine blew, enabling McLaren to take the lead ahead of Phil.[46][47][48][44] Phil was about 12 seconds behind Cooper by lap 95 and was continually reducing the gap.[46][47] By lap 99, he was only five seconds behind.[46][47] Ultimately, McLaren kept his nerve, taking victory by about 1.3 seconds, and claiming nine points in the Drivers' Championship.[46][47][48][44] Hill was second, while Bandini took third.[47][48][44] Surtees finished fourth, and Porsche's Jo Bonnier was seven laps down in fifth.[47][48][44]The race was one of attrition, with just those five drivers finishing the race. Because of this, Graham Hill took sixth, as everyone behind him had already retired.[48][44]

1967 Monaco Grand Prix

The 1967 Monaco Grand Prix was the second race of the 1967 Formula One World Championship. Occurring on 7th May, the race was ultimately won by Brabham-Repco's Denny Hulme, the future World Champion claiming his first win in the sport. However, the event is overshadowed by the fiery accident which claimed the life of Ferrari's Lorenzo Bandini.

The timing of the event was unusual, as it occurred five months following the opening South African Grand Prix.[50][51] It led some journalists, including from Motor Sport, to describe the Monaco Grand Prix as the first proper 1967 race.[51] Like with previous Monaco Grand Prix, only sixteen cars were allowed to qualify, with invitations given to the top veteran manufacturers, topping eleven entries in total.[52][51] Among those forced to fight for qualification included Jackie Stewart, who competed in an Owen Racing Organisation-owned BRM.[51] The sport was still transitioning from 1.5 to 3 litre engines, Lotus again being forced to rely on 2-litre engines for drivers Jim Clark and Graham Hill as the revolutionary Cosworth DFV was still not available.[51] Further bogging the team down was a shipping strike which prevented the team's transporter from reaching Monaco prior to the start of qualifying.[51]

Brabham Repco's Denny Hulme started strongly, though teammate and defending World Champion Jack Brabham suffered an engine failure early on Thursday's session, requiring an immediate substitution.[51] Another driver who impressed was Stewart, becoming the only driver that day to break the 1:30 mark.[51] However, with the Lotuses finally present, significantly faster times were posted on Friday.[51] Among the quickest was Honda's John Surtees, posting a time of 1:28.4.[51] Clark and Hill had swiftly made up for lost time with several laps below 1:30, while Stewart again performed strongly, this time in a H16 BRM as his other car suffered transmission issues.[51] Bandini proved over-aggressive in this session, crashing out at the Mirabeau hairpin.[51] Nevertheless, he redeemed himself on Saturday, achieving a time of 1:28.3, which put himself on provisional pole.[51] But just when it appeared the Ferrari driver would start first, Brabham finally capitalised on his replacement Repco power unit, achieving pole position on the last lap with a 1:27.6.[53][51][50] This dropped Bandini to second, with Surtees third, Hulme fourth, Clark fifth, and Stewart sixth.[53][51][50] Bob Anderson, Jean-Pierre Beltoise, and Richie Ginther all failed to make the final grid.[53][51][50]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix commenced on 7th May.[53] Bandini quickly took the lead from Brabham, whose day ended prematurely following a connecting rod failure, terminally damaging the Repco engine and causing oil to leak onto the track.[51][52][50][53] In the midst of dodging the stricken Brabham, Hulme and Stewart passed Bandini, Clark was stuck on the escape road, while Jo Siffert damaged his Cooper-Maserati's radiator.[51][50][52][53] Bandini was then passed by Eagle-Weslake's Dan Gurney, but quickly regained third when Gurney retired on lap five following a fuel pump failure.[51][53] As the drivers negotiated a still slippery track, Stewart passed Hulme for first on lap six, while Bandini defended third from Surtees.[51][50][52][53] The latter three all moved a spot when Stewart retired due to a broken differential on lap 15, as McLaren-BRM's Bruce McLaren began challenging both Bandini and Surtees.[51][50][53] After 27 laps, Hulme was considerably ahead, but Bandini gained some breathing space as Surtees' Honda engine slowly expired between laps 27 to 33.[51][50][52][53]

Clark made an extensive recovery, consistently setting new fastest laps and eventually challenging McLaren for third after 40 laps.[51][52][53] However, in a rare error for the Scot, Clark spun his Lotus entering the Tabac corner, terminally damaging his rear suspension after 43 laps.[51][52][50][53] Meanwhile, Bandini launched a bid for the lead, eventually cutting down Hulme's lead to eight seconds.[51][52][50] In contrast, McLaren lost ground as he experienced alternator issues, though was still able to race.[51][50] He eventually pitted for a new battery on lap 71, allowing Ferrari's Chris Amon to take third, with Hill not far behind.[51][50] After 70 laps, Hulme had truly regained control of the race, though it appeared Bandini was safe in second.[51][52] But 12 laps later, he suffered his fatal accident.[54][51][52][50][53]

With this, teammate Amon moved into second.[51][52][50] However, with nine laps remaining, Amon was forced to pit to replace a punctured right tyre, the damage suspected to have been sourced from Bandini's wreck.[51][52][50] Hill took second, but was a lap down from Hulme, who comfortably claimed his first World Championship victory.[51][52][50][53] Amon followed Hill in third, McLaren held on to take second, while Cooper-Maserati's Pedro Rodriguez and BRM's Mike Spence took the final points positions of fifth and sixth as they were the only other competitors still competing in the race.[50][51][53]

Death of Lorenzo Bandini

On lap 82, Bandini was maintaining second place, and was about to negotiate the Chicane du Port.[54][51][50][52] Laps prior, Motor Sport expressed concern that Bandini was over-exerting himself trying to catch Hulme, losing concentration and making minor errors approaching some corners.[51][54] Amon also believed his teammate was suffering severe fatigue.[55] These concerns proved valid, as Bandini entered the corner at too high a gear, fifth instead of the usual third or fourth.[54][51][55] He ended up clipping a wooden barrier at over 100 mph, which redirected him into straw bales guarding the harbour front, before finally smashing into a mooring bollard.[55][54][51][52] The wrecked car was then inverted, before igniting with Bandini unable to escape.[54][52][55][51][50]

Already, the situation was grim for Bandini.[56] However, a series of events contributed towards him needlessly suffering further horrific injuries.[54][56][52][55][51] The straw bales, which had already contributed towards the actual crash, soon fed the raging fire.[54][56][52][55] Several marshals arrived on-scene, but were unprepared as they lacked fireproof clothing and properly functioning fire extinguishers.[55][54][56][52] None had made sure to check on Bandini, assuming he had been thrown free of the car.[54] It took over five minutes to overturn the burning vehicle, as only ropes were available and the fire's intensity defeated several earlier rescue attempts.[54][55][52][56] By this point, the fire had seemingly died down.[55][54][56] A television helicopter reached the scene from above to capture the unfolding rescue efforts.[55][54][56] However, momentum from its blades ended up reinvigorating the fire, just as marshals were pulling Bandini out of the Ferrari.[55][54][56] In a panic trying to dodge the flames, the marshals accidentally dropped the Italian, who had been engulfed with flames once more.[55]

By the time Bandini was laid to rest near the roadside, he was covered in burns and foam.[54][52][55][51] Another critical mistake was made by the rescue effort, as they had assumed the driver had already perished and had overlooked him to prioritise extinguishing the fire.[54] Only sharp intervention from Giancarlo Baghetti, who found Bandini still breathing, ensured the latter was finally taken away from the track to the Princess Grace Polyclinic Hospital.[54][55][50] All these events occurred while the race itself still commenced, some drivers narrowly missing the accident scene.[52][55] This also prevented ambulances from reaching the accident scene, forcing Bandini to be taken to hospital by ship.[55][54] Despite reportedly improving somewhat while in hospital, it became clear to most that Bandini, who had suffered over 70% third degree burns and numerous internal damage, would still perish from his injuries.[55][54][51] Three days later, on 10th May, Bandini passed away, aged 31.[54][56][55][52][51][50] He had previously won the 1964 Austrian Grand Prix, and was described as a highly charismatic individual, as well as "one of the nicest people I've ever met" according to Amon.[55][54] As a mark of respect, Ferrari opted not to compete at the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix.[57]

Bandini's fatal accident led to heavy criticism of the track and the overall rescue efforts.[55][54][56] Aside from being woefully underprepared, it was also alleged by French television service ORTF that the Monaco firefighters had simply "walked away from the fire".[56] Further, the straw bales were cited as a key factor for the Ferrari being inverted, Amon stating that "nothing got a car upside down quicker than straw bales".[55][54][56] Thus, some changes were made to the circuit, with the straw bales replaced with guardrails, the chicane was moved further away from the tunnel, and, to avoid excessive fatigue, the race distance for future Monaco Grand Prix was reduced from 100 to 80 laps.[57][55][54] Despite Motor Sport criticising the changes as "feeble", the small safety improvements did yield tangible results.[57][55][54] At the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix, Johnny Servoz-Gavin experienced a similar incident as Bandini's.[55][54][57] But instead of causing the Matra-Ford to overturn, this did not occur upon hitting the guardrail, Servoz-Gavin being able to limp to the pits with terminal damage to his car.[55][54][57]

Availability

According to Issue 1,808 of Radio Times, footage of the 1958 French Grand Prix was included in a report by Sportsview on 9th July, with Moss himself providing commentary.[58][59][60] It is unclear how long the segment lasted, as the 30-minute program also included reports on the AAA Championships and the White City Jubilee.[58][59] The broadcast has yet to publicly resurface, although other race footage exists thanks to a British documentary. No footage of Musso's fatal accident and its aftermath is known to be available. Similarly, Issue 1,823 of Radio Times stated that a special 15-minute Sportsview episode reported on the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix on 22nd October, with Moss being the reporter.[61][62][60] Only newsreel footage of the race is publicly available.

The 1960 Dutch Grand Prix received full live television coverage from Belgian broadcaster BRT. It was also partially aired live by the BBC, ORTF, and NTS.[60] According to Issue 1,908 of Radio Times, 15 minutes were televised by the BBC as part of its Grandstand programming.[63][60] The television broadcasts have yet to resurface, although newsreel footage from British Pathé can be viewed online.[64] It is unclear whether the television broadcasts captured footage of Gurney's accident, but the newsreel does show the remains of the BRM.[64]

Footage and photos of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix and the fatal accident are widely available to view in documentaries and newsreels.[40] However, television coverage of the race remains missing; this includes four live airings of the race as part of the Eurovision Network, lasting around an hour and ten minutes.[60] Additionally, Issue 1,974 of Radio Times stated that the BBC provided highlights on the same days as part of Sportsview, with the 35-minute broadcast also containing a preview of a 1961 European Cup match between Gornik and Tottenham Hotspur, and a report of a rugby league match between Lancashire and New Zealand.[65][60] No television broadcast has fully resurfaced, but a fragment of the Eurovision Network coverage was included in a documentary.

The 1962 Monaco Grand Prix reportedly received partial live coverage from several television broadcasters.[60] Among these include a combined 3 hours and 30 minutes of coverage from Belgium broadcaster RTB, 2 hours and 15 minutes from the Netherlands' NTS, a combined 1 hour and 45 minutes from ORTF.[60] According to Issue 2,012 of Radio Times, 35 minutes were provided by the BBC, detailing the start and the end of the event.[66][60] American outlet ABC provided 90 minutes of highlights on 10th June 1962.[60] None of these broadcasts have fully resurfaced, though partial footage from the BBC and ORTF did resurface in documentaries, suggesting the full tapes still exist within each broadcaster's archives. Other footage, including a high-quality 70mm film from the German documentary Mediterranean Holiday, and newsreel footage from British Pathé, has also resurfaced.[67]

Meanwhile, the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix was partially televised live across the world, some broadcasts lasting for a few hours.[60] Among these include an ORTF broadcast, where footage of the rescue efforts on Bandini has since publicly resurfaced.[60] According to Issue 2,269 of Radio Times, the BBC's broadcast was split into three timeslots.[68][60] The first was a 25-minute exclusive segment reporting on the race start, harnessing footage presented by TMC and ORTF.[68][60] It then shared a 35-minute segment with coverage of the Lancashire-Worcestershire cricket match.[68][60] Finally, a 20-minute segment was shared with the aforementioned cricket match, documenting the closing stages of the event.[68][60] None of the BBC footage is currently publicly available, and indeed, most live coverage of the race is missing. However, a brief ABC highlights package was televised on 21st May 1967.[69][60] It provided colour highlights of the event, as well as of the rescue efforts.[69] This triggered major controversy, for it showed close-up footage of a severely burned Bandini being dragged away.[69] This led some publications, like The New York Times, to question whether broadcasting such close-up coverage exceeded the boundaries of decency.[69] This broadcast can be found online, including via Facebook and YouTube.

Gallery

Videos

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ultimate Car Page listing every French Grand Prix. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Racing-Reference detailing qualifying and race results of the 1958 French Grand Prix. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 F1 Destinations detailing the history of the French Grand Prix. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1958 French Grand Prix report. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 Grand Prix summarising the 1958 French Grand Prix and Musso's crash. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 ESPN summarising the 1958 French Grand Prix and Fangio's post-race comments. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ GP Racing Stats noting this was Hawthorn's final Formula One victory. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 Motorsport Memorial page for Luigi Musso. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 Racing News 365 detailing the only Moroccan Grand Prix to count towards the Formula One World Championship. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 ESPN summarising the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ Motor Sport detailing the Ain Diab Circuit. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 12.24 12.25 12.26 BBC Sport summarising the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix and how it marked an "end of an era". Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 13.27 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix report. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 Racing-Reference detailing qualifying and race results of the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ Motorsport Memorial page for Mike Hawthorn. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Motorsport Memorial page for Stuart Lewis-Evans. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 The Crash Photos Database detailing Lewis-Evans' crash and providing photos of it. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Circuits of the Past detailing the history of Zandvoort and the Dutch Grand Prix. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 Racing-Reference detailing the qualifying and race results of the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ Autoweek reporting on the return of the Dutch Grand Prix to the Formula One calendar. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 21.15 21.16 21.17 21.18 21.19 21.20 21.21 21.22 21.23 21.24 21.25 21.26 21.27 21.28 21.29 21.30 21.31 21.32 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1960 Dutch Grand Prix report. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 22.14 22.15 22.16 22.17 22.18 22.19 22.20 22.21 22.22 22.23 ESPN summarising the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix and the accident that claimed Aalder's life. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 23.12 23.13 23.14 23.15 23.16 23.17 23.18 23.19 23.20 23.21 23.22 23.23 23.24 23.25 Grand Prix summarising the event. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 ESPN noting that the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix was Ireland and Hill's first podiums, and summarising Gurney's crash. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 The Crash Photos Database detailing the Gurney-Aalders accident and providing photos of it. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 26.11 26.12 26.13 26.14 26.15 26.16 Racing-Reference detailing the qualifying and race results of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ Ultimate Car Page listing all instances of the Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ F1 Experiences detailing facts regarding the Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ Scuderia Ferrari Club detailing how Monza is considered the home of Ferrari. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 30.12 30.13 30.14 30.15 30.16 30.17 30.18 30.19 30.20 30.21 30.22 30.23 30.24 30.25 30.26 30.27 30.28 30.29 30.30 30.31 30.32 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1961 Italian Grand Prix report. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 31.00 31.01 31.02 31.03 31.04 31.05 31.06 31.07 31.08 31.09 31.10 31.11 31.12 31.13 31.14 31.15 31.16 31.17 31.18 31.19 31.20 31.21 31.22 31.23 31.24 31.25 31.26 31.27 31.28 ESPN summarising the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 32.00 32.01 32.02 32.03 32.04 32.05 32.06 32.07 32.08 32.09 32.10 32.11 32.12 32.13 32.14 32.15 32.16 32.17 32.18 32.19 32.20 32.21 32.22 Grand Prix summarising the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 33.00 33.01 33.02 33.03 33.04 33.05 33.06 33.07 33.08 33.09 33.10 33.11 33.12 33.13 33.14 33.15 33.16 33.17 33.18 33.19 33.20 33.21 33.22 33.23 33.24 33.25 33.26 33.27 33.28 33.29 33.30 33.31 33.32 33.33 33.34 33.35 33.36 33.37 33.38 33.39 33.40 33.41 33.42 33.43 Race Fans documenting the 1961 Italian Grand Prix and the disaster. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Stats F1 detailing the Drivers' and Constructors' Championship standings heading into the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Motorsport Memorial detailing the life and career of Rodriguez, including him becoming the youngest driver to compete at a World Championship event until 2009. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ NBC Sports noting Rodriguez was the youngest to qualify on the front row of a World Championship race until 2016. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 37.00 37.01 37.02 37.03 37.04 37.05 37.06 37.07 37.08 37.09 37.10 37.11 37.12 37.13 Motorsport Memorial page for Wolfgang von Trips. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ Stats F1 detailing the Drivers' and Constructors' Championship standings following the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ F1-Fansite detailing the list of Formula One World Champions by year and nationality. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 40.7 The Crash Photos Database detailing the 1961 Italian Grand Prix accident and providing photos of it. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 ESPN detailing von Trips and his "Taffy" nickname. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 F1 Chronicle detailing the history of the Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ Ultimate Car Page providing a list of Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 44.00 44.01 44.02 44.03 44.04 44.05 44.06 44.07 44.08 44.09 44.10 44.11 44.12 44.13 44.14 Racing-Reference detailing the qualifying and race results of the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ Topend Sports detailing the Triple Crown of Motorsport. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 46.00 46.01 46.02 46.03 46.04 46.05 46.06 46.07 46.08 46.09 46.10 46.11 46.12 46.13 46.14 46.15 46.16 46.17 46.18 46.19 46.20 46.21 46.22 46.23 46.24 46.25 46.26 46.27 46.28 46.29 46.30 46.31 46.32 46.33 46.34 46.35 46.36 46.37 46.38 46.39 46.40 46.41 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1962 Monaco Grand Prix report. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 47.00 47.01 47.02 47.03 47.04 47.05 47.06 47.07 47.08 47.09 47.10 47.11 47.12 47.13 47.14 47.15 47.16 ESPN summarising the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 48.00 48.01 48.02 48.03 48.04 48.05 48.06 48.07 48.08 48.09 48.10 48.11 48.12 48.13 48.14 48.15 48.16 48.17 48.18 48.19 48.20 Grand Prix summarising the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Motorsport Memorial page for Ange Baldoni. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 50.00 50.01 50.02 50.03 50.04 50.05 50.06 50.07 50.08 50.09 50.10 50.11 50.12 50.13 50.14 50.15 50.16 50.17 50.18 50.19 50.20 50.21 Grand Prix summarising the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix and Bandini's fatal accident. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 51.00 51.01 51.02 51.03 51.04 51.05 51.06 51.07 51.08 51.09 51.10 51.11 51.12 51.13 51.14 51.15 51.16 51.17 51.18 51.19 51.20 51.21 51.22 51.23 51.24 51.25 51.26 51.27 51.28 51.29 51.30 51.31 51.32 51.33 51.34 51.35 51.36 51.37 51.38 51.39 51.40 51.41 Motor Sport providing a detailed 1967 Monaco Grand Prix race report. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 52.00 52.01 52.02 52.03 52.04 52.05 52.06 52.07 52.08 52.09 52.10 52.11 52.12 52.13 52.14 52.15 52.16 52.17 52.18 52.19 52.20 52.21 52.22 ESPN reporting on the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix and Bandini's fatal accident. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 53.00 53.01 53.02 53.03 53.04 53.05 53.06 53.07 53.08 53.09 53.10 53.11 53.12 53.13 53.14 Racing-Reference detailing the results of the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 54.00 54.01 54.02 54.03 54.04 54.05 54.06 54.07 54.08 54.09 54.10 54.11 54.12 54.13 54.14 54.15 54.16 54.17 54.18 54.19 54.20 54.21 54.22 54.23 54.24 54.25 54.26 Motorsport Memorial page for Bandini. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 55.00 55.01 55.02 55.03 55.04 55.05 55.06 55.07 55.08 55.09 55.10 55.11 55.12 55.13 55.14 55.15 55.16 55.17 55.18 55.19 55.20 55.21 55.22 55.23 55.24 Motor Sport detailing the career and death of Bandini. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 56.00 56.01 56.02 56.03 56.04 56.05 56.06 56.07 56.08 56.09 56.10 56.11 10th May 1967 issue of Madera Tribune reporting on the death of Bandini. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 Motor Sport noting Ferrari did not compete at the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix and detailing the changes made following Bandini's death a year prior. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the Sportsview broadcast of the 1958 French Grand Prix. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Issue 1,808 of Radio Times listing the Sportsview broadcast of the 1958 French Grand Prix. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ 60.00 60.01 60.02 60.03 60.04 60.05 60.06 60.07 60.08 60.09 60.10 60.11 60.12 60.13 60.14 60.15 60.16 List of Formula One television broadcasts, including for the aforementioned races. Retrieved 17th Aug '22

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the Sportsview broadcast of the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ Issue 1,823 of Radio Times listing the Sportsview special for the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix. Retrieved 10th Sep '22

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the BBC's live coverage of the race. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 British Pathé providing newsreel footage of the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix, also including aftermath shots of Gurney's crash. Retrieved 16th Sep '22

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the BBC coverage of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix as part of Sportsview. Retrieved 28th Sep '22

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the BBC's live coverage of the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ Autoweek detailing the Mediterranean Holiday film of the 1962 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 6th Nov '22

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 Issue 2,269 of Radio Times detailing the BBC's coverage of the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix. Retrieved 31st May '23

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 The New York Times reporting on ABC's broadcast of the 1967 Monaco Grand Prix and the controversy of the broadcast showing graphic close-up footage of Bandini. Retrieved 31st May '23