£1,000 Reward (lost banned British drama film; 1913)

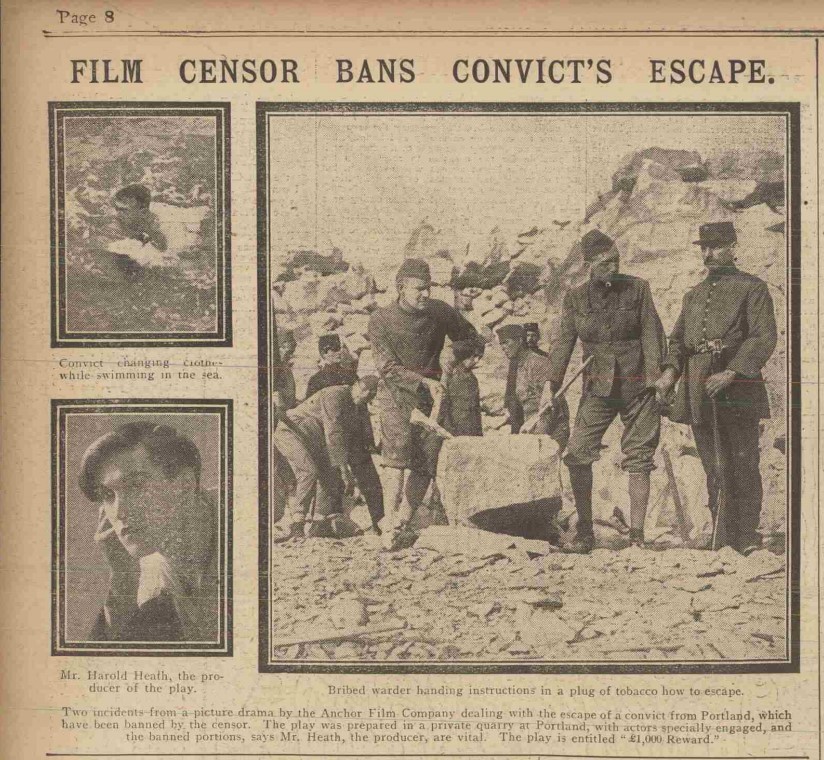

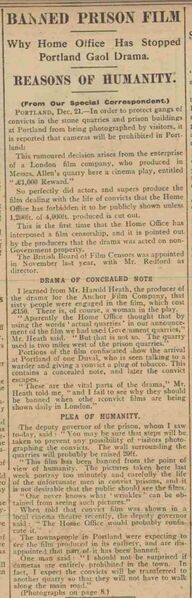

22nd December 1913 issue of The Daily Mirror summarising the film's ban and providing a few photos of it.

Status: Lost

£1,000 Reward is a 1913 British drama film produced by the Anchor Film Company. Directed by Harold Heath, it stars Heath as Jack Strong in a story involving an escapee of Portland Prison who later joins a coining gang operated by Countess Zula (Muriel Palmer). The film holds the dubious honour of becoming the first to be banned in the United Kingdom by the Home Office, triggered following the establishment of the British Board of Film Classification.

Background

Portland Prison (now known as HM Portland Prison and Young Offender Institution Portland) first opened in 1848.[1][2][3] Situated on the Isle of Portland,[4] it garnered a reputation for being an extremely tough institution.[1][2] Initially, hundreds of repeat offenders were housed there, where they were put to work on the island's construction projects including its harbour defences.[1][2] The gruelling conditions took its toll on the prisoners.[2][1] Particularly, some such as Frederick Goodey perished while working in the stone quarries.[5] Naturally, some prisoners were desperate to escape.[1][2] The attempts resulted in at least three murders of prison wardens and subsequent executions of convicts throughout the 1860s and 1870s.[1] However, some did escape the island's confounds, for a time anyway.[2] Though others had done so beforehand, William Bartlett recalled that he managed to escape through the usage of makeshift tools, but his newfound freedom was ultimately short-lived.[2] The majority of escapees only lasted a few months before they were recaptured.[2] Portland Prison has since been transformed into a category C institution, which houses both adult males and young offenders.[3][1]

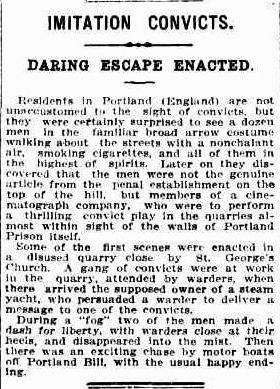

Though Bartlett and others had successfully escaped Portland Prison,[2] the institution was still trumpeted as being impenetrable by the 1910s.[4] Hence, the London-based Anchor Film Company realised that a play could be produced based on the premise of having a prisoner defy the odds.[6][4] To that end, Harold Heath and around 60 others travelled to the disused Messrs, Allen's quarry, not far from St. George's Church and a few miles from the Government-controlled counterparts.[7][6] Heath was not only the film's producer but he was also set to direct and take a starring role in it.[8][6] Some sources proclaim him as the first individual to direct and star in his own feature-length cinematic play.[9][10][11] According to the 27th December 1913 issue of Sydney's The Sun, it was a remarkable sight for residents to witness jovial "convicts", who were obviously actors for this project.[7] Aside from scenes being filmed at the quarry, it is also known that a chase sequence on motorboats was recorded off the coast of the Portland Bill.[7] Based on the film's theatrical poster, one boat eventually erupts into flames,[12] eventually leading to a sequence of events that results in a happy ending.[7] The film's production reportedly cost £150,[6] about £21,860 when adjusted for 2024 inflation.[13] The completed film ran for about 4,000 feet.[8][6][4] For some reason, the 22nd December 1913 issue of The Daily Mirror felt the need to mention women were involved in the play.[6]

Plot

Though a detailed plot summary has not been found, parts of the film's narrative have been preserved thanks to newspaper articles, the theatrical poster and a brief summary by the British Film Catalogue.[6][7][8] Heath stars as Jack Strong; though his role is not listed anywhere, one can assume Strong is either the main convict or the detective tasked to re-capture him.[8] The convicts work long, gruelling hours at the quarries near Portland Prison,[1][2] causing some to become desperate to escape.[7] A golden opportunity arrives when a steam yacht visits the island.[7] Its owner bribes one of the prison wardens, the latter of whom gives a convict tobacco.[14][7][6] Inside the tobacco is a message containing instructions on how to escape Portland.[7][14][6] When fog emerges, two convicts make a break for it, pursued by several wardens.[7][6] One convict enters the sea; confident he has defied his captives, he switches clothes and swims to the mainland.[14] Once on land, he soon meets Countess Zula (Muriel Palmer) who invites him back to her den.[8][12]

There, the escapee joins the Countess' coining gang.[8] These gangs worked to produce counterfeit coins, usually by clipping off the gold and silver that engrained them, replacing them with less valuable metals before creating fake international currency through the acquired clippings.[15] During the 1760s, the Cragg Vale Coiners led by David Hartley became the most famous coining gang, earning millions at the expense of nearly bringing the British economy to its knees.[16][15] However, the convict's newfound freedom is threatened by a detective and an accompanying flower girl called Bessie (Lily Saxby).[8] After the convict's cover is blown,[8] a pursuit by motorboat emerges, which ends when one bursts into flames.[7][12] The film culminates with a fight between the convict and the detective on the housetop, which ends in the latter's favour.[12][8][7] The detective presumably claims a £1,000 reward for the convict's capture and likely ends up with Bessie as per the "Hero gets the Girl" trope.[17][8][12]

Ban and Subsequent Censorship

£1,000 Reward was completed by December 1913 and had been unveiled in at least one theatre.[8][6] But just as it appeared the film would be showcased across the UK and Portland, it came under the scrutiny of the BBFC.[4][12][6] The BBFC originally began operations as the British Board of Film Censors (now British Board of Film Classification) in January of that same year, with George A. Redford instilled as its first President.[4][6][12] During its initial operations, around 120 films were reviewed per week by a board of examiners.[4] They could give a production a U rating for universal, an A for works containing adult content, or refer the film to Redford for a more thorough review of potentially problematic content.[4] Of 7,510 works reviewed that year, at least 22 of them were banned for various reasons including but not limited to being overly sexual, promoting animal cruelty or allowing "excessive drunkenness".[4][12] One film refused classification by the BBFC was an August 1913 newsreel by British Pathé after it filmed Dartmoor prisoners without express permission.[4]

Upon hearing of the film's completion and plot, the Portland Prison's Commissioner contacted the Home Office and demanded it be banned.[12][4] The Commissioner's main gripe concerned the film's potential to inspire actual convicts to conduct daring escapes from Portland.[18][10][4] He was especially aghast at the scene showing a bribed warden;[4][6] he believed this may inspire relatives of the prisoner to attempt to win the favour of corrupt officials, including through tobacco and other bribes.[12] A similar concern was the possibility Portland tourists might photograph the quarry convicts and Portland Prison's infrastructure upon the film's release.[6] Thus, to "protect" the prisoners and guarantee Portland's security, a push was made to remove the film from circulation.[6][4] In an interview with The Daily Mirror, Portland Prison's deputy governor insisted £1,000 Reward was too accurate in its depiction of prisoner life and feared it would subsequently produce "wrinkles" that could threaten the prison's security.[6] He reckoned Portland Prison's walls would need to be raised by at least 20 feet to avoid photographic scrutiny.[6]

The Home Office was sympathetic to the Commissioner's concerns and discussed the matter with the BBFC.[4][12] The two departments quickly achieved consensus that the film in its complete length was detrimental to the British public and security.[4][12] Therefore, the work was promptly banned by the Home Office, but not before the BBFC suggested a compromise.[4][6][12] Upon reviewing the work, the BBFC believed that about 1,200 feet of the 4,000-foot work needed to be removed.[6][4] Among scenes subject to censorship was the bribing of the warden; the convict swimming to freedom;[14] and ultimately, all references to Portland Prison.[4] Heath was displeased with the proposed censorship, as he felt that the removal of such scenes would completely break the film's narrative.[6][4] In an interview with The Daily Mirror, Heath was also displeased that his film was targeted when other convict-centric works had been released without any scrutiny.[6] He believed that the poster's claim the work contained "The only Convict Scenes ever taken in the actual Quarries at Portland" played a key role in the film's ban.[6] Portland residents were also displeased to learn of the ban and feared greater restrictions on future works set on the island.[6]

Ultimately, Heath relented and the seemingly "unshowable" edited version was given a U rating by the BBFC.[4][8] According to The Daily Mirror and other sources, £1,000 Reward became the first British film to be banned and censored by the Home Office.[6][10] Alas, the film was victimised in response to government fears that films were inspiring a growth in crime and other delinquent behaviour.[12] These concerns inspired the BBFC's creation, which centralised age ratings and media censorship in Britain and has since become an independent regulatory board.[19][12] The BBFC's website claims that since the mid-1920s, its decisions to ban or censor works have generally been accepted by relevant authorities.[19] Based on information provided by the British Film Institute (BFI), Heath also directed The Mystery of the £500,000 Pearl Necklace and Nobody's Child, which were also released in 1913.[20] Heath also featured in 1930s films Splinters in the Navy and Pal o' Mine.[20] The BFI did not find any other acting credits for Palmer, but discovered Saxby featured in ten further films from 1915 to 1916, which were mainly works produced by Weston Feature Film Company and the Broadwest Film Company.[20] Anchor was still involved in film production until at least the late 1920s.[20]

Availability

Despite the production's relatively dubious history,[4][10] £1,000 Reward has fallen into relative obscurity.[21] It prompted an appeal from the Portland Museum for more information, following a request from a local film student curious about the work's notoriety.[21] Some Facebook users happily obliged, with one even providing photos of the film from the 22nd December 1913 issue of The Daily Mirror.[21][6] However, the work does not appear to have survived with the BFI lacking a copy in its archives.[22] It is likely among the 80% of silent British films that have since been declared lost, as preservation efforts were generally lacking until decades after the work's original release.[23]

Gallery

Images

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 The Portland History Website documenting the history of Portland Prison. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Victorian Tales from Weymouth and Portland summarising Portland Prison's history and Bartlett's escape. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 GOV.UK summary of HM Portland Prison and Young Offender Institution. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 Behind the Scenes at the BBFC detailing the BBFC's inaugural year, including the controversy surrounding the banning of £1,000 Reward (p.g. 126-129). Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ Victorian Tales from Weymouth and Portland detailing the death of Frederick Goodey. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 22nd December 1913 issue of The Daily Mirror reporting on the film's ban and Heath's comments surrounding it (found on a Facebook post). Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 27th December 1913 issue of The Sun (Sydney) reporting on the film's production (found on a Facebook post). Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 British Film Catalogue listing of £1,000 Reward, noting its length, actor credits and a brief plot summary. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ The Guinness Book of Movie Facts & Feats stating that Heath was "The first director to direct himself in a full-length feature film". Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Portland: An Illustrated History summarising Heath's historic role and the film's ban. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ Empire Movie Miscellany stating that Heath was "The first director to direct himself". Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 The National Archives providing the film's theatrical poster and detailing its censorship. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ in2013dollars detailing the value of £150 in 1913 when adjusted for 2024 inflation. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 22nd December 1913 issue of The Daily Mirror providing photos of the film and summarising key scenes (found on a Facebook post). Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Malcolm Bull's Calderdale Companion detailing the history of coiners. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ Society for the Study of Labour History summarising the Cragg Vale Coiners. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ Scott Farrell summarising "The Hero gets the Girl". Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 1,423 QI Facts to Bowl You Over summarising the film's ban. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 BBFC detailing its history. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Based on British Film Institute information from the "Credits" and "Cast" links provided in its summary of £1,000 Reward (which cannot be linked directly). Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 2nd February 2021 Facebook post by Portland Museum requesting more information about the film. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ British Film Institute summary of £1,000 Reward and noting it does not possess a copy in its archives. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24

- ↑ The Conversation noting that around 80% of silent British films are considered lost. Retrieved 23rd Feb '24