Hillsborough Disaster (partially lost CCTV recordings and documents of football stadium disaster; 1989)

On 15th April 1989, during an FA Cup Semi-Final match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, an excessive number of Liverpool fans were allowed by police to enter two already overcrowded Leppings Lane pens at Hillsborough Stadium. The decision resulted in a human crush that would ultimately claim the lives of 97 spectators and injure 766. Aside from the disaster becoming the worst in British sports history and among the deadliest football-related events, it is also infamous for how the British press, South Yorkshire Police and politicians treated victims and their relatives in the aftermath. This resulted in a decades-long battle by the Hillsborough Families Support Group for justice, with a 2016 inquest declaring that the victims were unlawfully killed following a series of errors and an extensive cover-up campaign by South Yorkshire Police officials. During these inquests, revelations have emerged that CCTV tapes from Sheffield Wednesday's cameras were stolen on the day of the disaster. Additionally, key documents like minutes for the police planning meetings and the original police control room logbook have also reportedly vanished.

Background

Human crush incidents at football stadiums have occurred since the 1890s.[1] For instance, Fallowfield Stadium in Manchester was subject to two non-fatal overflow incidents during the 1893 FA Cup Final and the 1899 FA Cup Semi-Final clash between Liverpool and Sheffield United.[2] On 9th March 1946, 33 spectators were killed by a human crush at Burnden Park Stadium during an FA Cup match between Bolton Wanderers and Stoke City.[3] On 2nd January 1971, 66 perished at an exit stairway at the Ibrox Stadium during a Rangers-Celtic game.[4] On 29th May 1985, riots at the 1985 European Cup Final between Juventus and Liverpool at Heysel Stadium triggered the deaths of 39 after they were crushed by a concrete wall that also collapsed on them.[5] The Heysel disaster affected the reputation of Liverpool supporters, as their actions were blamed for the 39 deaths, culminating in English clubs being banned from European competitions for five years.[6][7][5] It contributed to the assumption from authorities that policing future matches would be based on tackling hooliganism rather than necessarily ensuring safety.[8][9]

Hillsborough Stadium houses the Football League club Sheffield Wednesday.[10] Opened in 1899, it became among the United Kingdom's most prominent stadiums, having hosted 1966 FIFA World Cup games and several FA Cup Semi-Final matches in the 1980s.[10][8] In 1934, it had 72,841 in attendance for Wednesday's FA Cup game against Manchester City.[10] By 1989, its official capacity was 54,000.[8] But while Hillsborough's prestige remained, its safety record proved concerning.[11][8] Its terraces were reinforced with steel fencing; while this reduced the possibility of pitch invasions, it also boxed spectators in, increasing the risk of human crushes should the stadium overflow.[12] Warning signs were apparent during four prior FA Cup matches;[11] on 11th April 1981 when Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers drew 2-2;[13][14][15] Coventry City's matches against Wednesday and Leeds United on 14th March and 12th April 1987 respectively;[16][17] and in an ominous sign, during Liverpool's 2-1 win over Nottingham Forest on 9th April 1988.[11] Common denominators of these incidents included the stadium reaching over-capacity, ineffective policing, and the Leppings Lane stands being most affected.[8]

Disturbingly, a Hillsborough disaster could have occurred eight years prior.[8][14][13][15] In the aforementioned Spurs-Wolves game, the police's decision to open Gate C so as to avoid extensive pressure at Leppings Lane's turnstiles caused the stand to be overloaded by 335 spectators.[8][13][14] This triggered a severe human crush that injured 38 Tottenham fans, some suffering broken limbs.[15][14] A fourth-minute Spurs goal may have also prompted a rush into the stands, contributing to the chaos.[14][13] But whereas South Yorkshire Police was certainly responsible for the injuries, their decisions to promptly open two perimeter gates and assist fans in climbing over the fences to reach the ground were cited as factors that prevented any fatalities.[8][15][14] The incident meant Hillsborough was forbidden to host another Semi-Final until 1987.[18]

Following the match, Sheffield Wednesday modified Leppings Lane; a South Yorkshire Police report concluded the main factor in the 1981 crush was fans being able to move freely sideways across an open terrace.[19][8] Therefore, the Lane incorporated new lateral fences that split the terrace into three pens.[8][13][19] However, the club and South Yorkshire Police collided regarding reducing the Lane's official capacity.[8] Police officials were concerned the terrace could not safely support the 10,100 the club promoted.[20][21][19][8] During the 2014-2016 inquest, structural engineer John Cutlack estimated the terrace could only safely contain 7,247.[21] However, Wednesday was unmoved and believed safety could be guaranteed providing the police's crowd control was more sufficient, having also deemed Tottenham fans responsible for entering the ground at the last minute.[19][8] Its chairman, Bert McGee, outright refused to believe anyone could perish within the stands.[22]

Leppings Lane underwent further changes in 1985;[23] it now had five pens following a police demand that more lateral fences be erected.[8] As a result, fans could now access a West Stand tunnel to reach central pens 3 and 4, which supposedly could hold 1,200 and 1,000 people respectively.[8] But the reality was different; neither pen reached the Green Guide's recommendations imposed following the Ibrox disaster, which found the outdated crush barriers were at unsafe heights, some failing the guidelines by 300%.[24][25][8] Other crush barriers had also been removed.[21] Thus, the pens were only safe enough to contain 822 and 872 respectively.[8] Additionally, the central pens usually reached full capacity faster than the others.[12][8] The police had hoped Wednesday would channel fans from the correct turnstiles to each pen directly, as this would allow accurate calculations of attendance figures within each.[8] Proposed turnstile re-designs which would allow for additional space outside Leppings Lane were also supported by the police, as were plans to increase turnstile numbers to 34.[26][23] However, the club found these recommendations cost-prohibitive.[8]

Ultimately, the other three incidents prior to 1989 showed the changes did little to improve safety.[11][18] Further, despite the pens being a radical change to the stadium's layout, no plans were put in place to update Hillsborough's safety certificate, which remained stagnant since 1979.[23][8] But another key factor in the impending disaster soon emerged. Fewer than three weeks before the disaster, Chief Superintendent Brian Mole was set to manage the Semi-Final, having previously done so for other big Hillsborough matches.[27][8] However, a hazing controversy at his branch led to his sudden reassignment.[27] In his place was Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield; not only did Duckenfield lack experience as a match commander, but he had never previously managed a Hillsborough game.[28][29][27][8] Worse still, he reportedly received inadequate training heading into the game.[29] On 22nd March 1989, he, Chief Inspector David Beal and others conducted a meeting to begin planning for the match.[27] Beal comprised the game's police operational plan alongside Inspector Steve Sewell, with the former claiming it was accepted by senior personnel.[30][27] He recalled that a minutes recording was made, but the document has been declared lost since at least 2014.[27]

Despite Duckenfield's inexperience, he had 1,444 police officers on match duty.[31] While this was a reduction of 19% from the 1988 Liverpool-Forest match, it still meant that nearly a fourth of South Yorkshire Police were working on the game.[20] Additionally, within the stadium's ground control room, he had access to then-revolutionary CCTV camera footage from each stand's turnstiles and pens, granting him an objective viewpoint of the status in and outside the stadium.[18][8] The previous year's clash, while affected by overflow, ended without any major incidents and so the 1989 operational plan was based around it.[30][8] But unlike 1988, the 1989 encounter faced a very different fate.[8]

The Disaster

Heading into the match on 15th April 1989, Liverpool and Nottingham Forest were among the Football League's top teams.[32][33] Naturally, a strong rivalry developed between the two clubs throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, and was considered Europe's most intense clash of the era.[32] Despite this, incidents of hooliganism between both sets of supporters were surprisingly infrequent.[33] Still, South Yorkshire Police's crowd control plan conformed to guidelines recommending opposing sides be split apart when entering the ground, made following the growing concern of English hooliganism since the 1960s.[34][35] Liverpool fans were allocated the Leppings Lane stands; the West and North stands combined held a capacity of 24,256 fans.[36][8] Meanwhile, Nottingham Forest supporters travelled to the South Stands and Spion Kop, which were cited as holding 29,800.[36][8] The allocations were deemed unusual since Liverpool fans were expected to appear in greater numbers.[37][38][8] Liverpool had complained about this in 1988, yet Mole insisted the decision was ideal for geographical, travelling and segregation reasons.[8][37][38] Requests by Liverpool and the FA to reverse this for 1989 were denied by Mole prior to his reassignment.[8] Liverpool's Chief Executive Peter Robinson claimed he requested the match be moved to Old Trafford, but this was also shot down.[38]

Additionally, twelve North Stand turnstiles present on Penistone Road were closed to ensure segregation, resulting in just a single Leppings Lane entrance being made available.[39][18][8] Liverpool fans would enter Hillsborough through only 23 turnstiles, compared to Forest's 60.[8][37] Only three gates and seven turnstiles were available on the terrace.[40][8] The first Leppings Lane gates were officially unlocked at 11:30 a.m., and the central pens, as expected, began to fill up faster than the others.[37][8] However, most Liverpool fans did not reach the ground until about 30 minutes before the planned 3 p.m. kick-off.[41][42][18][8] Two factors played a role in this; firstly, only one "football special" train had been in operation, compared to ten in 1987 and three in 1988.[8][42] Other Liverpool fans turned to coaches, but they were held up by M62 road works, including the construction of a new road.[42][40][8] Fans also had to navigate traffic at the Lane, which was allowed through despite being denied access the year prior.[8] Thus, a sudden influx of Liverpool spectators arrived, who were keen to enter the ground before kick-off.[18][41][42][8]

It was here that South Yorkshire Police, led by an inexperienced outside ground commander Superintendent Roger Marshall, failed to ensure adequate crowd control.[43][18][41][8] Unlike in 1988, there were no police cordons in place during the final approach to the ground.[8][18][43] Thus, fans reached Leppings Lane in various directions with no proper queues being enforced.[18][8] The closure of the Penistone Road turnstiles also meant an additional 6,000 spectators were present.[39][41] The few turnstiles in operation were processing triple the numbers of the Nottingham counterparts, but this was still not enough to prevent a dangerous bottleneck from emerging.[18][43] By 2:35 p.m. the crisis worsened to the extent that mounted police could do little to resolve it.[43][18][8] Marshall and his fellow officers became overwhelmed by the sheer numbers, having anticipated they would only need to perform occasional ticket and alcohol checks.[43] Even during previous FA Cup encounters, some bottlenecks arose that caused crush incidents at the stadium's gates and fences, but nothing of significant seriousness.[18][8] But in this clash, a human crush had begun to form within the growing audience and it became clear it needed to be alleviated to avoid a loss of life.[43][18][8]

With just over 15 minutes before kick-off, around 2,000 Liverpool fans had yet to be processed through.[43][18][42] During this time period, BBC commentator John Motson noticed something unusual within the Leppings Lane terrace.[42] Whereas central pens 3 and 4 were packed with spectators, the others barely had any fans whatsoever.[42] Inside the ground control room, Duckenfield, by his own later admission, had zero clue on resolving the situation.[43] His knowledge of Hillsborough's layout, turnstiles and safety record was extremely limited, and he became more out of his depth as the carnage unfolded outside.[43][28] But one option he had was to delay kick-off for twenty minutes; this had occurred in the aforementioned Tottenham-Wolves and Coventry-Leeds games, which were delayed by 15 and 20 minutes respectively.[8][42] Duckenfield decided to discuss this with his deputy, Superintendent Bernard Murray.[8] Murray assured Duckenfield that kick-off could commence at the usual time.[8] There were also apparent police guidelines that advised not to delay games for reasons within the fans' "control", nor do so once both teams entered the pitch.[44][8] Thus, kick-off was not delayed and Sergeant Michael Goddard, who was responsible for radio communications, denied further delay requests.[8][18][42]

This decision was cited as a major error since delaying kick-off for 20 minutes would have given ample time for fans to filter through the turnstiles.[18] Marshall himself never requested the match be delayed.[43][42][8] However, by around 2:48 p.m., the situation outside became desperate, as the lack of space made it difficult for spectators and police alike to breathe.[8][43] Marshall contacted Duckenfield, informing him point-blank that if Gate C was not opened, fatalities would emerge.[43][18][8] After pondering it for a few minutes, Duckenfield made the fateful decision to allow access through the gate.[43][18][8] As around 2,000 fans poured through the gate, one final error triggered the disaster.[43][18][41][8] In other big games, as soon as the central pens were filled to capacity, police presence would block incoming spectators from travelling through the central pen tunnel, but instead redirect them to one of the adjacent areas.[8][43][18][12] This did not occur as Duckenfield was overly focused on preventing and resolving possible hooliganism rather than assessing consequences like human crushes.[43][18][8][12]

Thus, the remaining fans travelled directly through the tunnel into pens 3 and 4.[41][18][42][12] Very few went to the adjacent pens thanks to poor signage.[42][8] Suddenly, between 1,296 to 1,430 were in pen 3 alone, over 3,000 were in both pens overall, and the surge of spectators caused those at the front to be forced into the fences.[41][42][8][12] Crushed between the fences and other people, some spectators began experiencing compression asphyxia, where they were unable to breathe because of the sheer pressure around them.[43] Meanwhile, Liverpool and Nottingham Forest began the game unaware of the Leppings Lane situation.[41][8] Four minutes in, Liverpool forward Peter Beardsley nearly gave his side the lead, but his shot was rebounded by the crossbar.[42] This triggered crowd surges in the affected pens; during this, one corroded crush barrier, which had been in operation since the 1920s yet was stated to be capable of containing a large crowd, collapsed and resulted in victims piling onto each other.[8][41][42]

For trapped fans, four main escape options were available that depended on their location.[41] At the front, some spectators climbed over the perimeter fence and onto the ground, while some eventually escaped when fence gates were unlocked.[45][41] Others resorted to climbing the sideways fences, which would safely place them in the mostly empty side pens.[41] Some were also hoisted up into the upper West Stand by fellow spectators.[41][43] But for those climbing over the fences, an unexpected barrier emerged; South Yorkshire Police officers.[46][45] Unlike in the Tottenham-Wolves game, where the police were credited for assisting fans escaping the crush, officers present at the 1989 match assumed spectators were attempting a pitch invasion, and began pushing escaping fans back.[46][45][8] Some individuals, moments away from safety, ended up back in the crush and subsequently perished.[46] Other officers outright ignored the pleas from trapped fans.[46] It was not until 3:05 p.m. that the match was stopped on the orders of Superintendent Roger Greenwood, the game's ground commander.[47][41] Like with Duckenfield, Greenwood lacked knowledge on effectively managing pen attendance.[47] Other police officers formed a cordon at the centre of the pitch to prevent clashes between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest fans, and did not participate in rescue efforts.[48][8]

Another critical mistake was made, this time by senior ambulance officer Paul Eason.[49][50][18] Eason, along with three colleagues, were situated at a Hillsborough corner, before responding to unusual Leppings Lane behaviour three minutes following kick-off.[49] Despite having a clear view ahead, Eason reportedly failed to properly check the affected pens nor heard the cries for assistance.[49][18] Crucial minutes passed before Eason declared a major incident, with police requesting ambulances by 3:08 p.m..[49][50][18] Eason later admitted he froze during his response to the growing disaster.[50] But while 42 ambulances promptly arrived outside the ground, just three made it onto the pitch and only two reached the disaster scene.[18][41] Most remained outside after crowd incidents were reported by the police.[18][41] While some medical personnel did provide crucial assistance, a lack of key equipment like stretchers and oxygen cylinders was apparent.[18] Some advertising boards were also utilised to ferry stricken victims to ambulances.[41] A few doctors were also distracted aiding victims with serious but not life-threatening injuries.[18] The majority of fatalities occurred inside the ground, with just fourteen who later perished having been taken to hospital.[41][18]

In total, 94 people were killed that day.[51] Four days later, 14-year-old Lee Nicol passed away in hospital.[51] Two other fans aged 22, Tony Bland and Andrew Devine, both ended up in persistent vegetative states.[52][53][51] Bland passed away on 3rd March 1993, following a historic court order which, with his family's support, allowed his life support to be turned off as it became clear his prognosis would never improve.[52][51] Devine did regain consciousness in March 1997 and was able to communicate via a touch device.[54][53] What made his recovery remarkable is that nobody with similar injuries had survived more than eight years, and he was expected to pass away after only six months.[53] While requiring round-the-clock care, Devine still attended some Liverpool games afterwards.[53] On 29th July 2021, Devine died aged 55 and was later declared by a coroner as the 97th Hillsborough victim.[53] Of the 97 victims, 90 were male and seven were female.[51] The oldest victim was 67, while the youngest was aged ten.[51] 766 others were injured.[8] To date, the Hillsborough disaster is the deadliest in British sporting history and the worst football stadium crush event.[1] It is also the third deadliest football-related disaster, behind only the Estadio Nacional and Accra Sports Stadium riots.[1]

Aftermath and Unlawfully Killed Verdict

While the Hillsborough disaster is already a notorious event in British history, its aftermath proved infamous because of the treatment the victims and their relatives received, in addition to the subsequent long battle for justice.[55][56][57][43] Even as the disaster was unfolding, South Yorkshire Police launched a campaign where they concealed their errors and pinpointed the blame entirely on Liverpool fans.[43][56][57] Duckenfield, 15 minutes following kick-off, was confronted by FA secretary Graham Kelly, who demanded an explanation for the crush.[58][43][56][57] Instead of admitting to his mistake, Duckenfield told Kelly that ticketless fans had barged through Gate C and therefore gained illegal entry into the ground.[58][43][57] Soon afterwards, this narrative was spread to the media, who none the wiser, reported on these police accounts.[43][55][56] As the game was being televised live by the BBC, commentator Motson relayed South Yorkshire Police's narrative to viewers, which consequently painted fans as the perpetrators of the disaster.[43][57][55] Among the few individuals who initially knew the real truth was Assistant Chief Constable Walter Jackson, after being informed by Marshall.[43] Jackson soon requested the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) investigate the disaster.[43]

In the days after the disaster, more police accusations against fans emerged.[57] Chief Superintendent Terry Wain and Chief Constable Peter Wright were among several high-ranking South Yorkshire Police officials who reportedly claimed that thousands of Liverpool fans had reached the ground at the last minute, many without tickets present.[59][60][57][56] Even worse, Wright allegedly instructed officers to report to the media that the spectators were heavily intoxicated.[59][57] Wain, who denied similar accusations, later admitted a report he provided to Taylor was "potentially misleading".[60][57] Even after only hours had passed, some CID officers had attempted to collect evidence of alcohol, including by interviewing relatives and taking pictures of litter.[43] The coroner, Dr Stefan Popper, also had all victims tested for alcohol in their blood irrespective of age.[61][43] Duckenfield's false narrative continued to spread, which alleged Liverpool hooligans forced their way into the gate and thus caused the disaster.[43][57][56] More disturbing allegations were spread by Inspector Gordon Sykes and Sheffield MP Irvine Patnick.[62][63][57] Among these claims included supposed hooligans who attacked police officers focused on saving lives, urinated on both officers and incapacitated spectators, and most egregiously, committed theft on deceased or otherwise dying individuals.[64][62][63][57]

Not helped were the initial media publications on the disaster.[65][66][64] While it was perhaps in the public interest to report on police accusations, several prominent newspapers spun the narrative that South Yorkshire Police's account was entirely factual.[65][64] The most infamous of these came from The Sun, who took Patnick's claims as gospel and subsequently lambasted Liverpool fans with its 19th April 1989 issue's heading entitled "The Truth".[64][57][55] To date, The Sun's reputation has never recovered in Merseyside, with an ongoing boycott making it a taboo subject within the region.[67][64][65] While The Sun received the most backlash, other newspapers like the The Sheffield Star, The Times and Manchester Evening News also published controversial news and opinion pieces.[65][66] UEFA President Jacques Georges also faced criticism, as he labelled Liverpool fans "beasts" following the disaster, most likely fuelled by the Heysel disaster.[7][65] Sheffield Wednesday were reportedly more fixated on the loss of ticket revenue than the disaster itself.[68]

In May 1989, the Hillsborough Family Support Group was established to not only support the families of deceased relatives but also to campaign for justice.[69] Nine years afterwards, the Hillsborough Justice Campaign was formed, with one of its main aims to also provide support for survivors affected by their experiences.[69] On 15th May 1989, the first inquiry into the Hillsborough disaster was conducted by Lord Justice Taylor.[70][55] Finalised in January 1990, the two Taylor Reports primarily criticised the lack of crowd control, particularly caused by zero methods like police cordons being utilised, the general lack of available turnstiles, and unsafe crush barriers.[71][70][12][55] Key criticisms focused on the failure to close the tunnel once it became clear the central pens were filled to capacity, as well as Duckenfield's decision not to delay kick-off.[71][70][12] Taylor additionally concluded that drunken fans, while not the main cause behind the disaster, did exacerbate it though noted intoxicated spectators were a minority.[71][70] In the final report, Taylor recommended that the terraces be replaced with all-seater layouts.[72][70][12][55] Most Football League stadiums, including Hillsborough, conformed to this, with the ground itself advertised to contain a more modest 34,854 as of 2023.[73][10][12]

Despite the verdict, no prosecutions were forthcoming to either South Yorkshire Police, Sheffield Wednesday personnel or other relevant stakeholders.[55] In June 1997, Lord Justice Stuart-Smith was appointed to re-evaluate the evidence.[74] Ultimately, he controversially ruled that his findings indicated no new inquiry was justifiable.[74] A private prosecution imposed by Hillsborough Families Support Group commenced in February 2000, against Duckenfield and Murray.[75][55] Alas, Murray was found not guilty, and though the jury failed to deliver a clear verdict on Duckenfield, Judge Justice Hooper ruled out a second trial, believing that the "public humiliation" the now former Chief Superintendent faced in the first would make further prosecution attempts oppressive.[75][55] At the time, it appeared the campaign for justice was over, as Hillsborough Families Support Group opted not to pursue another trial.[75]

But 20 years following the disaster, a debate within the House of Commons emerged over secret files, as growing calls for a new investigation emerged.[76][55] In December 2009, the Hillsborough Independent Panel, chaired by Bishop of Liverpool James Jones, was set up to re-assess the case.[77][8][55] Following pressure from campaign groups, the release of over 300,000 relevant documents occurred in October 2011 and were harnessed as part of 450,000 documents reviewed by the Panel, many of which were not previously available for the Taylor Report.[78][79][55][8] In the findings published in September 2012, the Panel conclusively determined that Liverpool fans had no accountability for the disaster, dismissing the notions that alcohol-induced hooliganism triggered the 97 deaths.[80][8] It also noted most relevant spectators were trying to save lives during the crisis.[8][18] Instead, by utilising evidence including the previous crush incidents, available CCTV footage, and expert statements to conclude that the police's crowd control failures combined with Hillsborough's safety issues like over-capacity and the FA's failure to adhere to warning signs caused the disaster.[8][80][55][11] Additionally, in direct contrast to Popper's original assessment that no victims who died that day survived beyond 3:15 p.m., the Panel found that emergency service failures meant 41 lives were lost when there was a significant chance of saving them had help arrived promptly.[8][80][61][55]

The Panel also uncovered another revelation: of the available police statements, 164 had been doctored so as to achieve the desired South Yorkshire Police narrative that solely blamed Liverpool fans.[81][8] These discoveries among others led to calls for a new inquiry, which began on 31st March 2014.[82][55] More new evidence and testimonies were provided, which uncovered the revelations surrounding the South Yorkshire Police's cover-up campaign.[58][43][59][60][62] The senior leadership's extensive attempts to blame drunken and ticketless Liverpool spectators were unearthed, while Sykes later accepted that the allegations he transferred, which originated from leadership figures, were indeed untrue.[59][60][62][57] Particularly, the release of bodily fluids was completely involuntary, caused by compression asphyxia.[67] But most prominently of all, Duckenfield would admit he outright lied about the Gate C situation and that he, like Eason, had also frozen at a critical time.[58][43][55] On 26th April 2016, the inquiry concluded that the Hillsborough victims were unlawfully killed and that a cover-up had indeed occurred.[83][55]

Over the next few years, Duckenfield along with five other men were charged under various counts.[84][55] Duckenfield was charged with manslaughter by gross negligence, while Chief Inspector Sir Norman Bettison was accused of four of misconduct in public office, as he was deemed an interested party in the South Yorkshire Police lies that were uncovered.[85][86][84][55] Chief Superintendent Donald Denton and Detective Inspector Alan Foster, along with solicitor Peter Metcalf, were charged with perverting the course of justice over their alleged roles in the alteration of police statements.[87][84][55] Ultimately, after two trials, Duckenfield was acquitted of all charges on 28th November 2019.[85][55] The cases against Bettison was dropped due to a lack of evidence, while the other former South Yorkshire Police personnel's charges were dismissed as the Taylor inquiry was not a court of law and thus no perversion of public justice could have occurred.[86][87][55] As of October 2023, only one individual has been convicted in relation to the disaster.[88][55] After one count was dismissed, Sheffield Wednesday club secretary Graham Mackrell was found guilty of a health and safety breach by failing to provide enough turnstiles on the day.[88][55] On 13th May 2019, he was fined £6,500.[88] South Yorkshire Police, as well as West Midlands Police both also faced a lawsuit from over 600 disaster survivors and relatives over the cover-up, with the case settled for an undisclosed amount on 4th June 2021.[89]

Missing CCTV Footage and Documents

Hillsborough Stadium was notable for containing an extensive CCTV system when such technology was uncommon in football stadiums.[18][43] Roger Houldsworth was appointed as Wednesday's technical director and thus became responsible for the club's surveillance system.[90][91][92][93] In 1986, he incorporated some club-owned CCTV cameras into Hillsborough and introduced an improved police surveillance system.[90] Houldsworth claimed 20 cameras were under the operation of Sheffield Wednesday; such cameras captured footage of the turnstiles and the nearby car parks, with none recording moments inside the ground.[90] This footage could be accessed by the club's own CCTV room.[90][91] Meanwhile, five police cameras were at Hillsborough; these ones notably captured footage in and outside the stadium and were able to zoom in and pan across a wide margin.[94][90][91] Duckensfield could access the footage from the police control room, which formed part of his decision to open Gate C.[90][18][43][94] The club CCTV room's central monitor could also view police footage, but naturally, only police officials could manipulate these cameras.[90][91]

During the inquest, Houldsworth emotionally recalled the disaster.[93] A week before, he had officially left his role at Sheffield Wednesday but was requested by Mackrell to monitor and maintain the CCTV system for an important clash as a one-off.[90][92] Houldsworth added new VHS tapes to 16 of the 20 club cameras (the others provided unrecorded infill area footage near the South Stand) 24 hours before matchday.[90] He and PC Harold Guest - who was going to replace Houldsworth - were situated in Wednesday's CCTV room when the disaster unfolded.[90][93] Already, he was concerned with the sheer number of people entering the packed central pens.[93][92] Following kick-off, he noticed people pouring onto the pitch.[93][92] He initially believed hooliganism had commenced only to realise the true situation.[93][92] He claimed he assisted in the rescue efforts of twelve people as the disaster occurred.[92] Houldsworth was among those who knew of Duckenfield's decision; he stated no subsequent order to re-close the tunnel ever emerged during radio communication.[91][92]

For the inquests, relevant club and police CCTV footage was showcased to the jury, primarily of incidents prior to Gate C's opening and the subsequent disaster.[95][96] In a sign missed by South Yorkshire Police, one man eleven minutes before kick-off actually escaped the pens after becoming affected by the overfilled terrace, which occurred before the fatal crowd surge.[95] But when investigators wanted to assess the full CCTV tape library, they were shocked to discover two recordings were unaccounted for.[8][37][91][92] The two tapes were stolen only hours following the disaster.[91][92][90] According to Houldsworth, the CCTV system was in operation until at least 4:15 p.m..[91] Following the disaster, he took the tapes into the Wednesday control room to avoid them being automatically erased and placed them in a double-door cupboard.[92][91][90] The cupboard contained a three-level lock but was otherwise not especially difficult to forcibly open.[92][90] Realising this, Houldsworth locked the control room and instructed a security guard not to permit anyone, not even South Yorkshire Police officials, to access it so that they could later be transfered to the club's solicitors.[97][92][91] Said room could be entered via the player tunnel.[92][91][90]

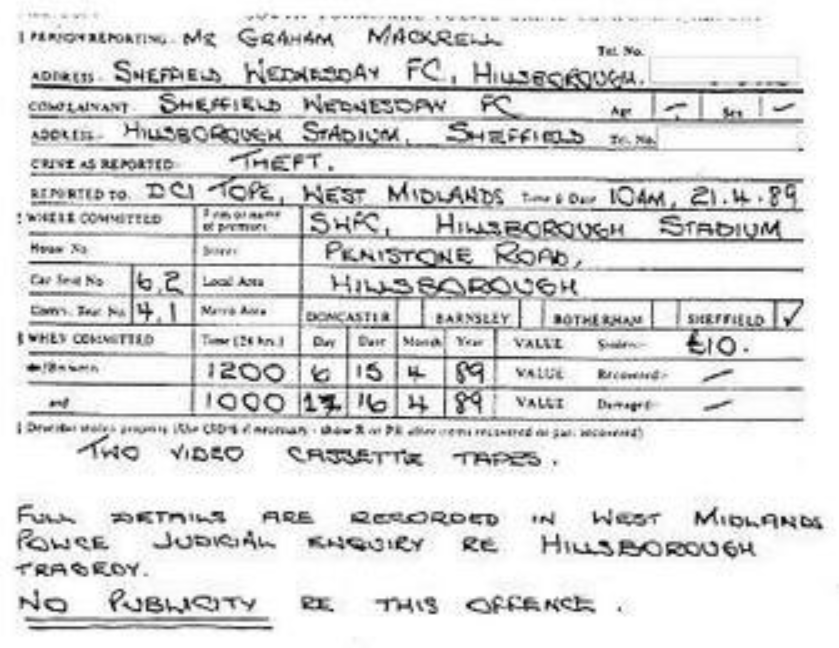

Houldsworth held one of only three keys that could unlock the door; one other was under Wednesday's head of security Douglas Lock's possession, but another was available within the caretaker's room.[92][97] Crucially, Houldsworth was then absent for two hours to meet with Mackrell and did not set a room alarm until he returned.[91][92] Following this, the electronics engineer went home.[91][92] When he returned the following morning, he noticed the cupboard doors had been opened.[91][92] He then discovered that two CCTV tapes had been removed; somehow, an individual had snuck past the tunnel patrol and obtained the contents, without leaving any evidence of a forcible entrance.[91][92] He subsequently reported the theft, which was documented on 21st April 1989.[98] The footage had no value outside of providing possible evidence for future inquiries.[98] Henceforth, Houldsworth believed there was no coincidence; whoever committed the theft was seeking to tamper with the investigation into the disaster.[97][91][98] The engineer also stated that the theft likely occurred during the two hours when the club's CCTV room was left unguarded.[91] He heavily implied South Yorkshire Police may have been responsible, as he remembered only "a few bobbies" being present near the CCTV room and the surrounding area following the disaster.[91]

It should be noted the missing footage likely had no crucial value for any Hillsborough investigation.[91][92][90] One tape, Houldsworth recalled, was for a Leppings Lane camera that was undergoing maintenance.[92][91][90] While it was recording footage, camera 2 was pointed towards a wall.[99][90] The other camera, designated camera 8, was fully functional but was capturing the unused turnstiles down Penistone Road.[92][90][99] Yet, recovering this otherwise irrelevant footage may still be of utmost importance in delivering justice for the 97 victims.[100][92] This is because their recovery may help to identify the culprit(s) behind the theft, who currently remain at large.[100][92][98] Houldsworth theorised the main motivation behind the theft was to obtain the tapes from cameras 3 and 4, which provided key evidence like Gate C being opened by police.[92][91] Another possibility, as noted by Sir John Goldring, the coroner for the subsequent inquest, is that camera 2 was also targeted under the mistaken assumption that it contained critical evidence, especially since it was situated at Leppings Lane.[99] The jury likely partly based their unlawfully killed verdict on the missing CCTV footage.[99]

The police CCTV recordings were also heavily scrutinised.[94][91] PC Trevor Bichard was assigned responsibility for this system.[94] While he had previous experience at Hillsborough, he stated during the inquest that Leppings Lane was often de-emphasised during his surveillance, having admitted he did not consider the responsibility of preventing it from overflowing with fans, especially as previous instances had occurred without incident.[94] But on the day of the disaster, Bichard and others within the police control room were fixated on the unfolding unrest outside.[101][94] Bichard recalled that his focus on capturing turnstile clips - including of people climbing over them - was merely to gather evidence of the sheer crowd numbers and any incidents rather than make decisions to resolve the crisis.[94] He remembered Duckenfield's decision to open the gate, criticising him for poor leadership and for having no contingency plan as the gate opened.[101] Bichard claimed no discussion commenced regarding re-closing the gate; however, a logbook he made revealed radio communication about closing Gate C had occurred.[102][103] Subsequent versions of this logbook notably omitted this note, providing further evidence of a possible cover-up.[103]

Regarding the CCTV cameras, Bichard claimed it was tough to view footage because of the monitors' low-quality output and placement, with one being forced to stand to fully see the imagery.[94] He also stated camera 5, which was recording the central pens, had suffered technical problems throughout the disaster.[94][91] It was also alleged the video from camera 5 was not retained because its recorder was unintentionally powered off by a police officer.[91][90][94] However, Houldsworth rejected these claims; while he acknowledged camera 5 did experience a lens flare mishap, this was sorted on the morning of 15th April.[90][91] He recalled the camera and the monitors displaying it were perfectly functional as the disaster unfolded.[91][90] Upon being asked whether the recorder could have been accidentally switched off, Houldsworth stated the power and record buttons were too small to be affected by any mishaps.[91] However, he noted South Yorkshire Police could have intentionally stopped the recording if they so wished.[91] Regardless of whether camera 5's recorder was accidentally or intentionally powered down, it has become apparent that the central pen clips the camera captured have become permanently lost.[91][94] Accusations also emerged in 2013 that police CCTV footage was altered in the original inquiry due to how certain scenes featured extensive jump cuts.[104]

On 14th June 2021, Twitter user The Wrong Kennedy delved deeper into the missing footage mystery. He examined the crime report filed on 21st April and noted a "no publicity" order had been made. Additionally, he discovered that a subsequent statement by Houldsworth had been doctored so that it no longer mentioned his efforts to protect the tapes. Like Houldsworth, The Wrong Kennedy believed the footage was stolen under the belief it contained critical evidence of the disaster.[98][91] Upon further analysing Hillsborough documents, including edited police statements and other suspicious evidence, The Wrong Kennedy claimed South Yorkshire Police carried out the theft as part of an extensive cover-up. His attention focused on a now-deceased detective responsible for gathering physical evidence, including CCTV footage. Interestingly, several close relatives of his quickly gave evidence of the disaster; some of this was in itself suspicious, including from one female relative who strongly supported the police account yet somehow contradicted herself concerning which team she supported. Considering this and the detective's connection to physical evidence, The Wrong Kennedy alleged the man was an interested party regarding the footage's theft and the overall South Yorkshire Police cover-up.[98]

Furthermore, The Wrong Kennedy noted other crucial evidence has never been unearthed. Alongside the missing minutes for the 22nd March planning meeting, the 29th March meeting minutes document has also somehow disappeared.[98] Additionally, a police logbook, which documented incidents at every Hillsborough game, had vanished following the disaster.[105][98] According to Goddard, he was informed by Murray that a new book had taken its place.[105] Yet, this book only documented the fateful match up until 2:21 p.m..[105] Some debriefing notes for the 1988 match regarding some officers around Leppings Lane disappeared, while the 1989 Police Operational Plan only exists in photocopy form.[98] All this, combined with edited statements, stolen CCTV footage, police lies that were later uncovered, the consistent blaming of drunken and ticketless fans, and other debunked allegations such as the infamous claim a police horse was burnt by cigarettes,[106] led to The Wrong Kennedy to conclude that the South Yorkshire Police had performed an extensive cover-up conspiracy, much of which remains unknown to the public.[98]

Availability

Rare CCTV, BBC and other police footage was assessed during the 2014-2016 inquests.[96][95] Some clips were released, which not only examined the police's handling of events but also pinpointed the final moments of those who perished in the disaster.[96][95] Understandably, Channel 5 among other broadcasters opted not to release the graphic and otherwise disturbing moments captured on film to either their television or YouTube channels. While the stolen CCTV footage contains no evidence of the crisis, it shall likely remain lost as its whereabouts and survival status are presumably closely guarded secrets by those involved in the theft.[91][100][98] Police CCTV camera 5, regardless of whether its recorder was intentionally or accidentally terminated, contains no surviving footage of the disaster.[91] Finally, the whereabouts of the missing planning minutes, logbook and other relevant documents remain completely unknown.[98][105][27] Considering that the inquiries have since ended, it is extremely unlikely any of these documents will ever publicly resurface.[98]

Gallery

Videos

See Also

- 2022 UEFA Champions League Final (lost CCTV footage of crowd incidents during international football match; 2022)

- Bradford City vs Lincoln City (partially found footage of Football League Third Division match; 1985)

- Serbia vs Albania (found footage of abandoned UEFA Euro 2016 qualifying match; 2014)

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Football-Stadiums listing the deadliest football stadium disasters and how they occurred. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Manc detailing Fallowfield Stadium and its two non-fatal overflow incidents. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Manchester Evening News summarising the Burnden Park diaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian detailing the 1971 Ibrox disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 History documenting the Heysel disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian detailing how Heysel damaged Liverpool's reputation. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 18th April 1989 issue of The Glasgow Herald reporting on Jacques Georges' comments following the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 8.28 8.29 8.30 8.31 8.32 8.33 8.34 8.35 8.36 8.37 8.38 8.39 8.40 8.41 8.42 8.43 8.44 8.45 8.46 8.47 8.48 8.49 8.50 8.51 8.52 8.53 8.54 8.55 8.56 8.57 8.58 8.59 8.60 8.61 8.62 8.63 8.64 8.65 8.66 8.67 8.68 8.69 8.70 8.71 8.72 The Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel published September 2012. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian detailing how the policing of the game was based on tackling hooliganism. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Stadium Guide summarising the history of Hillsborough Stadium. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 The Standard reporting on the FA ignoring warning signs heading into the 1989 game. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 Football Stadiums documenting the history of football stadium terraces, their safety concerns, and how they were banned following the Hillsborough disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 BBC News reporting on the 1981 Spurs-Wolves human crush. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 The Guardian reporting on the 1981 Spurs-Wolves human crush. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Hotspur HQ detailing how fatalities nearly occurred during Tottenham Hotspur's 1981 FA Cup match with Wolverhampton Wanderers. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Archived Coventry Observer summarising overflow incidents in two Coventry City games in 1987. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Coventry Telegraph reporting on the human crush that occurred during the 12th April 1987 game between Coventry City and Leeds United. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 18.14 18.15 18.16 18.17 18.18 18.19 18.20 18.21 18.22 18.23 18.24 18.25 18.26 18.27 18.28 18.29 18.30 18.31 18.32 BBC News summarising the five key mistakes that caused the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Correspondence between Sheffield Wednesday and South Yorkshire Police following the 1981 human crush. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 The Guardian reporting on concerns surrounding Lepping Lane's official capacity and the extent of police officers attending the game. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 The Guardian reporting on John Cutlack's information surrounding Hillsborough and its safety issues. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on calls for an inquiry following the 2012 Hillsborough Independent Panel report. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 BBC News reporting on Hillsborough's safety certificate not being changed following the introduction of pens and other changes in 1985. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Herald Scotland reporting on Leppings Lane crush barriers failing to meet Green Guide guidelines. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Glasgow Times summarising how the Ibrox disaster's lessons formed the basis of the Green Guide. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ BBC News reporting on proposals for redesigned turnstiles made in 1984. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 The Guardian reporting on Duckenfield being transferred in place of Mole and the missing initial planning minutes. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 BBC News reporting on Duckenfield's lack of match commander experience heading into the game. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 The Guardian reporting on the revelation Duckenfield received limited training as a match commander. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 ITV News reporting on the lack of contingency plan in the event of crowd congestion for the match. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ BBC News reporting on the names of 1,444 officers on match duty being passed over to the Independent Police Complaints Commission, and the revelation 164 police statements had been doctored. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Independent detailing the Liverpool-Nottingham Forrest rivalry during the 1970s and 1980s. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 The Anfield Wrap detailing the Liverpool-Nottingham Forest rivalry and how hooliganism between the clubs was generally infrequent. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Starter Soccer explaining the need to separate opposing fans during key matches. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Sports History Weekly detailing the rise and fall of English hooliganism that started in the 1960s. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 The Telegraph reporting on the different allocations for Liverpool and Nottingham Forest fans. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Liverpool Echo reporting on Liverpool being allocated just 23 turnstiles, which was done for geographical reasons. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Liverpool Echo reporting on Peter Robinson's comments surrounding a last-minute attempt to have the match be held at Old Trafford. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 BBC News reporting on the twelve North Stand turnstiles that were closed on the day. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 The Guardian noting Liverpool had access to only three gates and seven turnstiles to the terrace. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 41.00 41.01 41.02 41.03 41.04 41.05 41.06 41.07 41.08 41.09 41.10 41.11 41.12 41.13 41.14 41.15 41.16 41.17 BBC News documenting the key events of the Hillsborough disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 42.00 42.01 42.02 42.03 42.04 42.05 42.06 42.07 42.08 42.09 42.10 42.11 42.12 42.13 42.14 Shropeshire Star documenting the causes for fan delays. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 43.00 43.01 43.02 43.03 43.04 43.05 43.06 43.07 43.08 43.09 43.10 43.11 43.12 43.13 43.14 43.15 43.16 43.17 43.18 43.19 43.20 43.21 43.22 43.23 43.24 43.25 43.26 43.27 43.28 43.29 43.30 43.31 43.32 The Guardian detailing South Yorkshire Police's key mistakes in managing the game, and the lies conjured up following the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ ITV News reporting on police policy not to delay matches for factors within the crowd's "control". Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 BBC News reporting on South Yorkshire Police attempting to prevent some people from escaping. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 The Guardian reporting on fans being pushed back into the crush by police, with some officers ignoring the initial pleas for help. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 BBC News reporting on Roger Greenwood expressing regret for his role in the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Liverpool Echo reporting on the police cordon at the halfway line. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 BBC News reporting on Eason's mistakes in managing the emergency response to the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 BBC News reporting on Eason admitting he froze during the disaster response. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 BBC News summarising each victim of the Hillsborough disaster (published before Devine was declared as the 97th victim). Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland documenting the case of Tony Bland and the court order to have his life support be turned off. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Liverpool Echo reporting on the passing of Andrew Devine and his life following the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Independent reporting on Andrew Devine regaining consciousness. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 55.00 55.01 55.02 55.03 55.04 55.05 55.06 55.07 55.08 55.09 55.10 55.11 55.12 55.13 55.14 55.15 55.16 55.17 55.18 55.19 55.20 55.21 55.22 55.23 55.24 BBC News detailing the timeline following the disaster itself. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 Liverpool Echo documenting the cover-up over Hillsborough. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 57.00 57.01 57.02 57.03 57.04 57.05 57.06 57.07 57.08 57.09 57.10 57.11 57.12 57.13 BBC News summarising the five key myths spread about the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Independent reporting on Duckenfield admitting he lied about the Gate C situation. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 The Guardian reporting on Peter Wright allegedly instructing officers to spread the drunken fan narrative. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Sky News reporting on Wain admitting the report he provided in the Taylor inquiry was "potentially misleading". Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Daily Mirror summarising the criticism of Dr. Stefan Popper over his role in the original investigation. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 BBC News reporting on Gordon Sykes declaring the claims he shared were untrue. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 ITV News reporting on Irvine Patnick's role in spreading untrue claims. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 The Justice Gap detailing The Sun's infamous "The Truth" publication. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 Hillsborough Football Disaster on the media coverage surrounding the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Pies and Prejudice: In Search of the North summarising The Times' controversial opinion piece made by Edward Pearce. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 The Guardian documenting The Sun's allegations being debunked and how it has never regained its reputation in Merseyside. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Daily Mail reporting on Sheffield Wednesday demanding ticket compensation a month following the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Anfield Road summarising the main Hillsborough support groups. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 70.4 Hillsborough Football Disaster summarising the Taylor Report. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 The Interim Taylor Report. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Final Taylor Report. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Football365 noting Hillsborough Stadium's current maximum capacity as of early 2023. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Liverpool Echo summarising the controversial Lord Justice Stuart-Smith ruling. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 The Guardian reporting on Judge Justice Hooper ruling out a retrial in 2000 against Duckenfield. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ BBC News reporting on unseen files potentially being released. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Home Office announcing the formation of the Hillsborough Independent Panel. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on over 300,000 unseen documents being released to the Hillsborough Independent Panel. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Channel 4 reporting on the 450,000 documents that were assessed by the Panel. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 BBC News summarising the key findings of the Hillsborough Independent Panel. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Independent reporting on how 164 police documents were doctored. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on the start of the 2014-2016 enquiry. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Independent reporting on the unlawful killing verdict. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Business Insider reporting on the six individuals charged in connection with the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 ESPN reporting on Duckensfield being acquitted of manslaughter by gross negligence in November 2019. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 ESPN reporting on Sir Norman Bettison's charges being dropped. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 BBC News reporting on charges against three South Yorkshire Police personnel being dropped. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 BBC News reporting on Graham Mackrell being fined £6,500 after being found guilty of one health and safety breach. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Sky Sports News reporting on disaster victims and relatives receiving compensation from two police forces. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 90.00 90.01 90.02 90.03 90.04 90.05 90.06 90.07 90.08 90.09 90.10 90.11 90.12 90.13 90.14 90.15 90.16 90.17 90.18 90.19 90.20 Archived Liverpool Echo reporting on Houldsworth's comments surrounding his time at Sheffield Wednesday, his work on the CCTV systems and his role that began with fixing police camera 5. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 91.00 91.01 91.02 91.03 91.04 91.05 91.06 91.07 91.08 91.09 91.10 91.11 91.12 91.13 91.14 91.15 91.16 91.17 91.18 91.19 91.20 91.21 91.22 91.23 91.24 91.25 91.26 91.27 91.28 91.29 91.30 91.31 The Guardian reporting on Houldsworth's account of the stolen CCTV tapes and dismissing the allegations surrounding police camera 5. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 92.00 92.01 92.02 92.03 92.04 92.05 92.06 92.07 92.08 92.09 92.10 92.11 92.12 92.13 92.14 92.15 92.16 92.17 92.18 92.19 92.20 92.21 92.22 92.23 Liverpool Echo reporting on Houldsworth detailing how the CCTV tapes became lost and his theory regarding their disappearance. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 93.3 93.4 93.5 The Guardian reporting on Houldsworth's comments about his role on the day and assisting in rescue efforts. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 94.00 94.01 94.02 94.03 94.04 94.05 94.06 94.07 94.08 94.09 94.10 Liverpool Echo reporting on Bichard's account surrounding his responsibility in handling police CCTV, as well as his claim camera 5 was not functioning correctly. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 Sky News reporting on CCTV and other footage being shown to the Hillsborough inquests jury. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Daily Mirror reporting on "horrific" Hillsborough footage being shown to the jury. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Daily Mirror reporting on Houldsworth claim that the theft was "no coincidence". Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 98.00 98.01 98.02 98.03 98.04 98.05 98.06 98.07 98.08 98.09 98.10 98.11 98.12 The Wrong Kennedy's Twitter thread detailing the stolen CCTV footage and key missing documents. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 24th February 2016 issue of Liverpool Echo reporting on the jury being asked to determine whether the missing CCTV tapes contained crucial evidence of the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 Channel 4 summarising the stolen CCTV tapes mystery and noting no culprits nor motivations have been deduced. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 The Guardian reporting on Bichard's comments criticising Duckenfield's leadership during the disaster. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ Liverpool Echo reporting on Bichard being accused of lying by claiming no discussion to close Gate C emerged. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 BBC News reporting on newer versions of Bichard's logbook not containing the radio conversation notes. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on allegations surrounding tampered police CCTV footage. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 Liverpool Echo reporting on the missing original police logbook and Goddard's comments surrounding its disappearance. Retrieved 31st Oct '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on the burnt horse claim being debunked by prosecutors. Retrieved 31st Oct '23