Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene (lost film of alleged legitimate lynching incident; 1897)

|

|

Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene (also known as Lynching Scene at Paris, Texas) is an 1897 alleged actuality film. Produced and distributed by the International Film Company for independent exhibitors in June 1897, the recording apparently depicted a riotous crowd executing a prisoner in the state of Texas. The work's lost status, combined with the International Film Company's refusal to impart key information regarding the lynching, makes it very difficult to verify or debunk its authenticity.

Background

Forged in October 1896, the International Film Company was a joint venture by former Vitascope Company and Edison Manufacturing Company employees, Charles H. Webster and Edmund Kuhn respectively.[1][2] Though the pair would produce original works primarily within the actuality genre,[3] their initial films simply attempted to "reproduce" successful works released by the Edison Manufacturing Company.[4][1][2] At the time, Thomas Edison could do little to stop this, as his inaugural films were not copyrighted.[5] Ultimately, Edison got the last laugh as not only was he able to file copyright protection for his later productions,[1] but his subsequent legal action caused the International Film Company among others to swiftly depart the US film industry by 1898.[6][7][2]

Among the Edison films that the International Film Company "reproduced" included two 1895 mondo recordings made by Alfred Clark.[8] The first of these, titled Indian Scalping Scene, depicted a group of Indians killing a tenderfoot.[9][10][8] Two years later, in June 1897, the International Film Company released Scalping of a Tenderfoot,[11] later known as Scalping Scene by Thundercloud, the organisation having boasted that Thundercloud was a "genuine" Indian in its marketing.[3] But perhaps the more lucrative endeavour were productions surrounding lynching incidents.[12][13][9] This trend began with the release of Clark's A Frontier Scene, which depicted the execution of a horse thief by a group of enraged cowboys.[9][12][10][8] The Edison Manufacturing Company later renamed the film to Lynching Scene and Lynching of a Horse-Thief,[10][13][8][9] presumably to capitalise on the lynching "trend".[12] Whatever the case, sources like Before the Nickelodeon and The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture remark Edison had already begun to attract viewers intrigued of seeing mondo concepts like executions and gore.[10][9] It should be noted that Indian Scalping Scene and Lynching Scene have both been lost to time.[8]

Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene

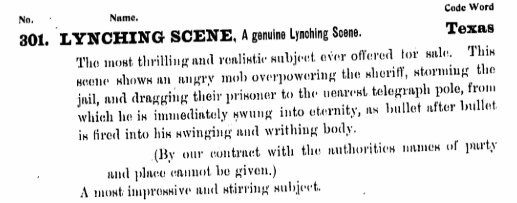

Armed with the knowledge surrounding the success of Edison's mondo films, the International Film Company set out to create their own lynching recording.[14][3][13] In the International Photographic Films, 1897-1898, which documented most of the organisation's films, a listing can be found for a production titled Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene.[15][16][3] With a length of 75 feet, the film allegedly depicted a riotous crowd charging towards a jail located somewhere in the state of Texas. After a sheriff's resistance attempts fail, the crowd is able to retrieve a male prisoner and forcibly position him at a nearby telegraph pole. The prisoner is then hit by a barrage of bullets, ending his life in a brutal fashion.[17][3][14] Having aimed to sell the recording to independent exhibitors for $15 ($564.46 adjusted for 2024 inflation[18]), the International Film Company claimed the incident's full location and its victim was classified per an agreement with the relevant authorities.[3][14][17][15] But interestingly, the company previously did reveal its location, as a June 1897 advertisement in The Phonoscope stated the film was originally titled Lynching Scene at Paris, Texas.[11][17] However, a subsequent promotion in the November-December 1897 edition revealed the work was retitled to Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene.[19]

Most sources, such as Corporeality in Early Cinema, Lynching and Spectacle, and Mario Slugan, believe the film was either a re-creation of an actual lynching or a mere forgery.[17][16][15] Slugan, in particular, questioned whether all the scenes could even be captured in a film touted as being only 75 feet in length.[15][3] Meanwhile, in his piece titled Cataloguing Contingency for the book Networks of Entertainment, Jonathan Auerbach identified multiple hyperbole claims made about the film and fellow International Film Company work Drowning Scene at Rockaway, particularly the insistence of the productions being "realistic" or "genuine".[14][3] The organisation also marketed the film as "The most thrilling and realistic subject ever offered for sale".[3] Additionally, one International Film Company work was confirmed to be a forgery, which tricked viewers into supposedly seeing USS Maine footage before she famously sank on 15th February 1898,[20] when it was actually just of her sister ship.[21]

But Slugan noted that because of the organisation's refusal to impart key incident information, combined with how filmmakers were often invited to planned lynchings and executions (e.g. The Hanging of William Carr and An Execution by Hanging[22]), it is virtually impossible to fully debunk the film's claims to legitimacy.[15] However, with the revelations the film was originally released as Lynching Scene at Paris, Texas in June 1897, it considerably narrows down the list of possible lynching incidents the film captured or replicated.[11][17] Lynchings were a pervasive societal problem throughout the 1800s; the Archives at Tuskegee Institute reported that approximately 4,743 lynching incidents were recorded between 1882 to 1968, with 1,297 white and 3,446 black victims.[23] Meanwhile, around 3,500 such incidents transpired according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[24]

It is noted that when the first lynching pictures emerged in the 1890s, lynchings were considerably less common in Northern states than in previous decades, but had begun to reflect growing racial tensions in Southern ones through the targeting of African American men.[9] Paris, Texas particularly bore witness to the infamous 1893 lynching of Henry Smith, a black labourer who was accused of the murder of four-year-old Myrtle Vance.[25] The subsequent torture and burning of Smith by a predominantly white crowd drew mainstream attention.[25] Hence, if Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene was indeed a forgery, its original title may have been used to capitalise on Paris' notoriety following Smith's execution.[11][25] On a separate lost media mystery, rumours abounded that Smith's screams were captured on a phonograph.[26][25] Though speculation persists several lynchings of African Americans were recorded in this fashion, Gustavus Stadler debunked the now-lost recordings as being re-enactments sold as part of the "descriptive speciality" genre.[26]

Similarly, in her book Lynching and Spectacle, Amy Louise Wood theorised the victim, regardless of the film's legitimacy, was probably African American based on the work's synopsis.[16] She noted that not only did the description match several real Southern lynchings of black men, but executions of white victims were typically announced as such by other films, including The Hanging of William Carr.[16][22] As for whether real lynchings occurred in Paris during 1897, the Archives at Tuskegee Institute indicates that 158 incidents were recorded in various American cities and towns that year, 123 involving black victims.[23] If one occurred in Paris by June 1897, such an incident received little if any media coverage. In his extensive research for the book Without Sanctuary, James Allen collected and researched numerous photos of US lynchings.[27] Of the 81 listed on the accommodating website, hotel porter Charles Mitchell's lynching was the only one to occur during that timeframe.[28] It transpired on 4th June 1897 and saw Urbana, Ohio residents overpower the sheriff and gain access to Mitchell's cell, Mitchell having been accused of rape and robbery of a white woman.[28] Though the capture is similar in nature to the film's narrative, the different location and means of execution (hanging) make it extremely unlikely the production captured or replicated Mitchell's death.[3][28]

Considering the International Film Company's hyperbole yet deliberately unclear film synopsis,[14][15] as well as its dubious record following the USS Maine fakery,[21] sources like The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture instead declare The Hanging of William Carr as the first verified recording of a legitimate lynching incident.[9] Still, Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene was reportedly showcased in Dallas, Texas around the same time as Edison's Lynching Scene[13][12] Little is known regarding the work's commercial success, but it likely did piggyback on Lynching Scene's notoriety.[13] Lynching productions were a major hit in predominantly white Southern areas, often being re-played in montages.[16][12] The Vicksburg Evening Post remarked that Lynching Scene drew high praise for being "realistic" and certainly helped satisfy curious viewers.[16] However, Wood theorises lynching films were additionally popular because not only did audiences cheer for the death of the lynching victim,[16] but they also helped reinforce racial superiority.[13] She argues it was no surprise films with a clear racist agenda, such as Edison's Watermelon Eating Contest, were typically played alongside the lynching productions in areas like Dallas.[13] Thus, these films' "legitimacy" probably played less of a commercial influence than what the International Film Company anticipated.[16][3]

Availability

Ultimately, the majority of the International Film Company's works, including Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene, are considered lost.[14] Indeed, School Is Out and Dewar's Scotch Whiskey/Scotch Dance are among the rare exceptions to have resurfaced.[29][30] Poor preservation efforts mean it is unlikely to ever be recovered, just like over 90% of other pre-1929 American films.[31] Thus, with no images having resurfaced either, the mystery surrounding the film's actual legitimacy is likely to remain unsolved.

See Also

- An Execution by Hanging (lost execution footage of Edward Heinson; 1898)

- Drowning Scene at Rockaway (lost film of alleged legitimate drowning accident; 1897)

- The Hanging of William Carr (lost execution footage of American child murderer; 1897)

- Lynching of Rashaad Staggie (found on-aired death footage of South African gang leader; 1996)

- Within Our Gates (partially found silent film; 1920)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rutgers-New Brunswick School of Arts and Sciences summarising the founding and early history of the International Film Company. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Who's Who of Victorian Cinema biography on Webster. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 International Photographic Films, 1897-1898 providing film summaries of the majority of the International Film Company works. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 summarising the establishment of the International Film Company and how it originally "duplicated" Edison films (p.g. 167). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company summarising how the International Film Company's early Edison duplicates were perfectly legal (p.g. 153). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ American Cinema 1890-1909: Themes and Variations summarising Edison's extensive legal action that caused numerous film companies to leave the industry (p.g. 48). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company noting the International Film Company closed its doors to avoid legal action from Edison (p.g. 115). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Films by the Year biography on Clark. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture Volume 19: Violence summarising Indian Scalping Scene and A Frontier Scene/Lynching Scene and claiming The Hanging of William Carr was the first to record an actual lynching (p.g. 63-64). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company summarising how Indian Scalping Scene and A Frontier Scene/Lynching Scene reflected a market interested by mondo and death recordings (p.g. 56). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 June 1897 issue of The Phonoscope listing of Lynching Scene at Paris, Texas and Scalping of a Tenderfoot (p.g. 14). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Violence in American Society: An Encyclopedia of Trends, Problems, and Perspectives summarising the growing popularity of lynching and recordings of it in Southern states of America (p.g. 211). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 summarising how Southerners were attracted to films depicting lynches back in the late 1800s (p.g. 119-122). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Cataloging Contingency summarising Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene and Drowning Scene at Rockaway and questioning their authenticity (found in Networks of Entertainment: Early Film Distribution 1895-1915, p.g. 205-207). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 The turn-of-the-century understanding of 'fakes' in the US and Western Europe summarising Lynching Scene, A Genuine Lynching Scene and how there is a small possibility the film could be legitimate (p.g. 735). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 summarising Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene and theorising that the victim was most likely African American based on the film's synopsis (p.g. 135-136). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Death by a Thousand Cuts summarising Lynching Scene at Paris, Texas (the film's original title) and claiming it was merely a re-creation of an actual event (found in Corporeality in Early Cinema: Viscera, Skin, and Physical Form, p.g. 89). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ in2013dollars noting $15 in 1897 money is equal to $564.46 in 2024. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ November-December 1897 issue of The Phonoscope promoting Lynching Scene: A Genuine Lynching Scene (p.g. 13). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Naval History and Heritage Command summarising the sinking of USS Maine. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 summarising a film that the International Film Company misled viewers into believing it featured USS Maine (p.g. 167). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 detailing An Execution by Hanging and The Hanging of William Carr, two films of legitimate executions (p.g. 125-131). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lynching statistics from 1882-1968 provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Bush Theatre noting NAACP figures surrounding lynching incidents between 1889-1922. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 ThoughtCo documenting the lynching of Smith. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Never Heard Such a Thing: Lynching and Phonographic Modernity discussing and debunking rumours that various African American lynchings were recorded live on phonographs (p.g. 1-20). Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Without Sanctuary summarising Allen's research into photographs and postcards of US lynchings. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Without Sanctuary detailing the lynching of Mitchell. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ School Is Out, a 15-second film. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ Dewar's Scotch Whiskey/Scotch Dance, a 30-second film. Retrieved 5th May '24

- ↑ The Film Foundation reporting on the majority of silent American films being declared lost forever. Retrieved 5th May '24