1954 Rugby League World Cup Final (partially found footage of international rugby league game; 1954)

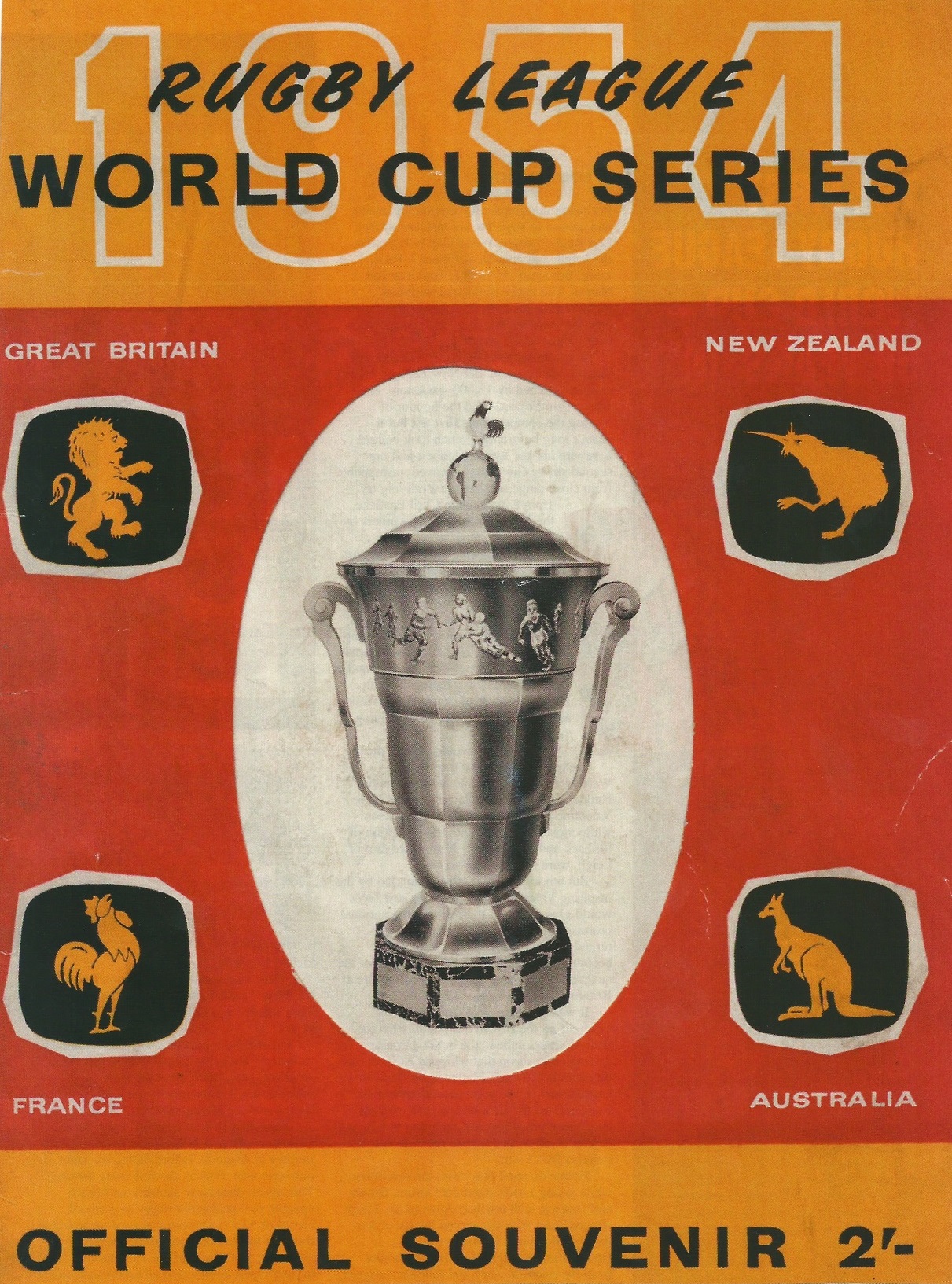

The 1954 Rugby League World Cup Final culminated the inaugural running of rugby league's largest global tournament. Occurring on 13th November at the Parc des Princes in Paris, it saw Great Britain edge out hosts France 16-12 to claim their first of two titles, in what was deemed an upset victory for the Lions. The Final received live television coverage by the BBC and RTF, via the Eurovision Network.

Background

A Rugby League World Cup was debated in January 1935, but the tournament's conceptualisation only truly began in 1944.[1] French rugby league was established in the late 1930s but had suffered badly under Vichy France rule during the Second World War.[2][3][4][5][1] Vichy was eager to rid the country of the sport, particularly due to its Popular Front and French Resistance connections.[2][3][5] The sport was banned in France on 19th December 1941, with its assets transferred over to rugby union.[2][1][3][5] Players were also forced to accept a move to rugby union, or face imprisonment among other consequences.[3][2] Following France's liberation in 1944, rugby league was legalised again but faced a tough time regaining its ground over rugby union.[2][1][3][5] Still, the French Rugby League was re-formed that same year under Marcel Laborde's presidency, with French Resistance veteran and former rugby union player-turned-rugby league loyalist Paul Barrière as vice-president.[1][3][5] Barrière is credited in forcing the French government to overturn its ban, by successfully appealing to the Ministry of Justice to overrule the Ministry of Sport's judgement.[5][3]

In 1947, Barrière succeeded Laborde as president.[3][1] For the next few years, he began developing plans for a possible Rugby League World Cup to be hosted in his home country.[3][1][5] This included proposing the International Board of Rugby League (IBRL), which came into fruition in 1948 and gave France influence in future international events.[6][1] Four years later, in November 1952, Barrière officially unveiled plans for a Rugby League World Cup, which he said would take place between 16th-31st May 1953.[7][1] It was hoped the tournament would guarantee French rugby league's financial future, with Barrière anticipating it would accumulate £24,000 in revenue.[1][4][5] The plan was met with resistance from Australian and New Zealand representatives, who felt the travel costs for a French-hosted tournament were prohibitive.[1][5] Promises that France would invest £36,000 into the tournament, would pay for all travel expenses, and give the competing sides £2,000 each for other expenses, ensured Oceanic support.[1][3] The deal also meant that if the tournament generated £5,000 in profit, all of it would be allocated to the hosts.[1] Any surplus afterwards would be equally split, as would 80% of ground attendance revenue.[1] The World Cup would be delayed until October 1954, so to avoid clashing with Britain's tours in Australia and New Zealand.[1][7]

Very few sports had initially followed FIFA in introducing a World Cup tournament.[8][3] Rugby union for instance did not have its own World Cup until 1987.[9][8] Back then, World Cups were not actually deemed prestigious in the United Kingdom, cultural values that put Great Britain's participation in jeopardy.[10][11][12][3] While travel would be of little concern, a large proportion of the Lions' top players felt their Ashes encounters were more important.[3][10][11][5] Additionally, some could not come due to Royal Navy commitments, while others rejected the small wages offered.[1][11][12] While Great Britain did compete in the tournament, all but three who competed in the recent Ashes withdrew.[3][11][12][5] Among the three was Dave Valentine, a Scotsman who played for Huddersfield and had captained the team at the Ashes.[11][12][10] He was now expected to lead essentially a second-tier team, seemingly putting the Lions' chances of winning to near zero.[11][5] Worse, the Great Britain campaign received limited backing; Valentine was expected to fulfil training and coaching duties, as the team lacked dedicated personnel, hotel accommodation and even spare rugby balls.[11][5]

In contrast, France was considered the pre-tournament favourites.[11][10][9] They had won the 1952/1953 series against Australia 2-1, and a dominant 31-0 victory over the United States in January 1954 led to the Americans being withdrawn from the inaugural World Cup over their lack of competitiveness.[13][14][11][1][3] France were particularly counting on fullback Puig Albert.[4] But the Aussies could not be ruled out, for they had achieved a 2-1 1954 Ashes Series victory over a top-tier Great Britain.[15] The tournament ultimately only consisted of four teams, as plans for the USA to be replaced with Italy, Wales, or Yugoslavia came to nothing.[16][1][5] Nevertheless, the 1954 World Cup proved commercially and critically successful, attracting at least 10,000 fans per game and accumulating 138,329 in overall attendance.[16][1][5] Interestingly, the highest attended match was not the Final, but instead the group clash between Great Britain and France.[16][4] The tournament generated £45,000 in revenue, providing a £7,000 profit.[1] This led to the World Cup's future being secured; while Barrière refused this request during his lifetime, his family gave blessing for the trophy to be named in his honour following his pass in 2008.[3][1][9][5] Barrière himself had provided the original trophy.[4][11]

The Tournament

The tournament would be played under round-robin rules, with the top two ranking teams progressing to the Final.[16][11] It kicked off on 30th October, with France overcoming New Zealand 22-13.[17][18][19][4] Despite this, winger Jimmy Edwards is credited for landing the first-ever try at the tournament.[19][17] However, tries from Jean Audobert, Raymond Contrastin, Joseph Crespo, and Guy Delaye, combined with Puig Aubert delivering the tournament's first goals and drop goal, helped the hosts ease out in front by the second half.[17][18][19] Aubert was declared the man of the match for his goals (one being from 55 yards away) and for nullifying many Kiwi attacks via his kicks. New Zealand's Jim Amos was not exactly thrilled with France's provocative tactics, criticising them as against the spirit of rugby league football. Nevertheless, The Sydney Morning Herald summarised that France fully deserved the victory, with Eastwood praised as New Zealand's top player.[18]

A day later, Great Britain took on Australia.[20][18] While the Aussies' backs proved overly aggressive in tackling the opposition and obtaining the ball, their early efforts were nullified by the Lions.[18] Britain's new line-up showed they were no second-rate team, opening the scoresheet and earning a 12-5 half-time score.[18][20] The Lions continued outclassing their Ashes foes in the second half thanks to their superior backs.[18] The team eventually scored six tries overall, including two apiece by Gordon Brown and Phil Jackson.[20][19] Worse came for the Aussies as Duncan Hall suffered an ankle injury, taking him out of play ten minutes into the second half.[18][20] Keith Holman and Ken McCaffery also picked up leg injuries.[20] Australia scored three tries in consolation, one occurring late on thanks to a defensive error.[20][18] While Duncan Hall and captain Clive Churchill both carried the Aussies to some breakthroughs, it was not enough to turn the tide of play, allowing the Lions to win 28-13.[18][20][19][4]

The Oceanic sides, therefore, promptly required victory as they met on 7th November.[21][22][23] The Kangaroos completely outpaced the Kiwis, taking a 16-2 lead by the interval.[21][4] Australia added another 17 by the game's end, with six different players scoring tries, including three by Alex Watson. Noel Pidding also added five goals for the Kangaroos.[21] A sole try by Lenny Eriksen and six Ron McKay goals were the only contributions for New Zealand, as they crashed to a 34-15 defeat.[21][22][23][4] On the same day, a French record 37,471 turned up at the Stade Municipal in Toulouse, which has never been surpassed as of 2023.[24][25] In a close affair, GB narrowly led France 8-7 at half-time, scoring three tries overall from Brown, Gerry Helme, and David Rose, in addition to two goals from Ledgard.[24] However, two tries from Raymond Contrastin, combined with a sole Joeseph Krawzyck try and two Aubert goals, ensured the hosts earned a 13-13 draw.[24][23][22] The result eliminated New Zealand from Final contention; the European sides simply needed a draw each to qualify, with Australia needing a win against France.[23][22]

The final games occurred on 11th November.[26][27] Ultimately, Australia were left to rue errors that prevented two tries and a goal from being scored in a tough encounter.[28] France took a 10-5 lead at the interval, with Vincent Cantoni, Raymond Contrastin, and Jacques Merquey all scoring tries.[26] Aubert added three goals, with France eventually achieving a score of 15.[26] In contrast, Kel O'Shea provided the Kangaroos' sole try, with Noel Pidding delivering a single goal.[26] Australia failed to score throughout the entire second half, crashing to a 15-5 defeat.[26][28][4] The Aussies nevertheless partly blamed questionable referee decisions for their defeat.[28] Meanwhile, Great Britain completely outclassed New Zealand, scoring seven tries, two from Frank Kitchen, and four Ledgard goals.[27] In contrast, New Zealand failed to score any tries and made no additions following the interval, with only three goals by Ron McKay preventing a whitewash.[27] The Lions won 26-6, progressing to the Final against France and leaving New Zealand with a 100% loss record.[27][4][16]

The Final took place on 13th November with 30,368 in attendance at the Parc des Princes.[29][30] France was deemed slight favourites, even by Australia,[26] but the previous game had certainly taken its toll as the side lost Delaye and showed battle scars elsewhere.[30] Initially, the hosts did put the challenge to the Lions in the early stages, exploiting defensive gaps and winning scrums courtesy of Jean Audoubert.[30] However, under Valentine's captaincy and its forwards, Great Britain began controlling play as the interval approached.[30] 8-4 to the Lions at halftime, France nevertheless took the lead early in the second thanks to Cantoni's try.[30][29] However, Great Britain fought back, with its forwards credited for helping their side dominate the remaining minutes.[30] Ledgard added two goals, while Brown's two tries and sole contributions from Helme and Rose edged out Aubert's conversions and Cantoni's try.[29] Brown's second try was declared as the play that settled the tie, despite a late France comeback.[5] In the end, France was overshadowed by Great Britain, the latter claiming the inaugural Rugby League World Cup by winning 16-12.[29][30][5][4] Overall, Brown earned the most tries at the tournament with six, while Ledgard scored the most overall with 29.[16]

Post-match, Valentine agreed the Australia game somewhat crippled France's offensive might.[30] Nevertheless, the Scotsman's captaincy is cited by sources like The Offside Line for turning a team of seemingly "no-hopers" into a formidable force.[11][12][5] Valentine believed the lack of expectations and the team's reliance on the Scottish folk song The Massacre of Macpherson proved highly impactful motivators for the Lions.[12][5] Every Lions player earned a £25 bonus (worth over £560 in today's money) and a penknife.[11][12] Following this initial triumph, Great Britain won the 1960 and 1972 editions and finished runners-up to Australia in 1957, 1970, 1977, and 1992.[31] They also entered the record books as the first British side to win any World Cup.[5] In subsequent World Cups, the British Isles have competed as separate teams, though none have yet won the World Cup as of the 2022 edition.[32][31] France's quality dipped following 1954, though the team did reach the 1968 Final by upsetting the Lions 7-2.[33][31] They ultimately lost the Final 20-2 to Australia, and have never reached that stage since as of 2022.[31][33]

Television Coverage

The 1954 Rugby League World Cup commenced in the early years of rugby league television coverage.[34][35][36] The BBC first televised the sport by airing the 1948 Challenge Cup Final, though subsequent broadcasts proved few and far between.[35][34][36] This was mainly because of concerns regarding the possible link between television coverage and reduced ground attendance, as well as claims the BBC de-emphasised rugby league in favour of rugby union.[34][36][35] Nevertheless, both the BBC and Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF) were interested in covering the Final, seeing its obvious importance for their respective countries.[37][38] RTF would provide direct coverage; however, the footage was successfully relayed to the United Kingdom courtesy of the Eurovision Network, which had launched in June 1954.[39][37][38] It was notably utilised to provide pan-European coverage of that year's FIFA World Cup in Switzerland.[39]

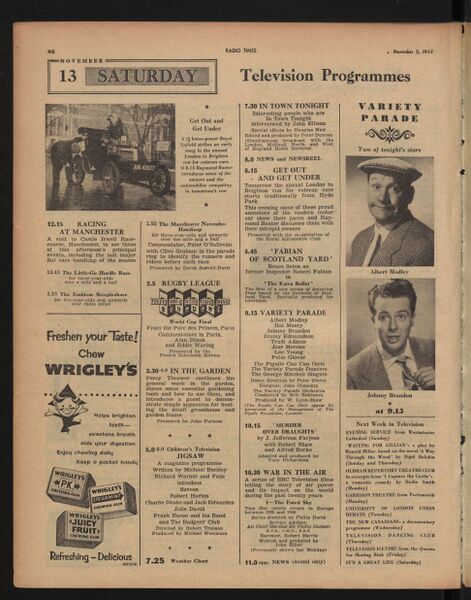

Issue 1,617 of Radio Times stated the entire match was aired, with commentary provided by Alan Dixon and Eddie Waring.[37][38] Overall, it proved a major hit in the United Kingdom, attracting several million viewers.[5] It must be noted that the broadcast came a year following the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, which caused an explosion in television's popularity.[5] Still, not everyone owned a television back in 1954, forcing congregations into the houses of those who did.[40] For example, rugby league commentator Ray French recalled watching the Final with others at his aunt's house. He remembered finding the coverage compelling, though noted television signals were especially prone to interference. This prevented him and others from seeing Brown's winning try, as the signal was interrupted by a bus temporarily stopping nearby to pick up passengers.[40] While the television broadcasts certainly attracted an audience, concern again rose when the Final delivered a lower attendance than the untelevised Great Britain-France group game.[34][16] Ultimately, the link between television and ground attendance proved unfounded by the late 1950s, with blame instead centring around hosting club matches around the same time as international events.[34]

Availability

The Final was televised in an era where telerecordings occurred infrequently.[41][42] The BBC had recorded some sports output dating back to the England-Italy November 1949 football match, and had also begun to fully preserve major sporting events like the 1953 FA Cup Final via film.[43][44][41] However, recordings did not become a regular occurrence until the BBC and other organisations harnessed videotape in the late 1950s.[41][42] It is possible the BBC and RTF did preserve the game, though the only publicly available match footage is sourced from newsreels.[40] When French discussed his memories of watching the Final, the BBC Sport video produced in 2013 exclusively harnessed the British Movietone newsreel rather than its own coverage.[40] This suggests the television coverage has not survived or is buried deep within the BBC archives in a low-quality form. Further evidence comes from the fact that recorded output often received repeat broadcasts, with the 1953 FA Cup Final telefilm, for example, airing two days following the match.[45][46][44] No signs exist that the 1954 Rugby League World Cup Final was as lucky.[42]

Gallery

Videos

Image

See Also

- 1924 NSWRFL Premiership Final (lost radio coverage of rugby league game; 1924)

- 1927 Challenge Cup Final (lost radio coverage of rugby league game; 1927)

- 1948 Challenge Cup Final (partially found footage of rugby league game; 1948)

- Christchurch vs High School Old Boys (lost radio coverage of charity rugby game; 1926)

- England 11-9 Wales (lost radio coverage of Five Nations Championship game; 1927)

- England 16-21 Scotland (partially found footage of Home Nations Championship game; 1938)

- Great Britain 20-19 New Zealand (partially found footage of international rugby league game; 1951)

- North Sydney Bears 19-21 Balmain Tigers (lost footage of NSWRFL Premiership season game; 1961)

- Scotland 21-13 England (lost radio coverage of Five Nations Championship game; 1927)

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 November 2013 issue of Men of League detailing how the inaugural Rugby League World Cup was formed and its success (page 50-51). Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 The New European documenting Vichy France's attempt to rid France of rugby league. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 The New European documenting the life and career of Barrière. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Archived 188 Rugby League summarising the 1954 Rugby World Cup's conceptualisation and the matches. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 Independent documenting the turbulent rise of French rugby league and how Great Britain achieved an unlikely World Cup win. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ International Rugby League summarising its history. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 19th January 1953 issue of The Sydney Morning Herald reporting on early plans for the World Cup, including its original May 1953 proposal. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 International Perspectives of Festivals summarising the introduction of other World Cups following the FIFA World Cup's formation. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 League Unlimited summarising the Rugby League World Cup's history and how it is significantly older than rugby union's version. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Sports Gazette summarising how Great Britain won the tournament. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 The Offside Line detailing the career of Valentine and how he guided Great Britain to glory. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 The Scotsman detailing how Valentine led Great Britain to an against the odds victory. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ Rugby League Project summarising the France-Australia 1952/53 series. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ Rugby League Project summarising the France-United States match in January 1954. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ Rugby League Project summarising the 1954 Ashes Series. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Rugby League Project summarising the results and other statistics of the tournament. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the France-New Zealand match. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 18.9 1st November 1954 issue of The Sydney Morning Herald reporting on the France-New Zealand and Australia-Great Britain games. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 TotalRL summarising the first two games and the Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the Great Britain-Australia match. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the Australia-New Zealand match. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 9th November 1954 issue of The Sydney Morning Herald reporting on the Australia-New Zealand and Great Britain-France matches, as well as previewing the final group games. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 8th November 1954 issue of The New York Times reporting on the Great Britain-France and Australia-New Zealand matches. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the France-Great Britain group game. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ Serious About RL noting the France-Great Britain group game remains the highest attended in France as of the present day. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the France-Australia game. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the Great Britain-New Zealand game. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 13th November 1954 issue of The Canberra Times reporting on the France-Australia match. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Rugby League Project detailing the result of the Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 14th November 1954 issue of The Sydney Morning Herald reporting on the Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Top End Sports providing a list of Rugby League World Cup Finals. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ The Guardian reporting on the British Isles teams compete separately for future World Cup and Tri-Nations competitions. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Rugby League World Cup summarising France's upset 1968 victory over Great Britain. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Rugby League in the Twentieth Century detailing the limited television coverage of rugby league in the 1950s, and concern regarding whether the broadcast reduced the Final's stadium attendance. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 BBC Sport in Black and White detailing the BBC's early rugby league coverage. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Transdiffusion detailing the concern regarding whether television coverage reduced stadium attendance. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the BBC's coverage of the Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Issue 1,617 of Radio Times listing the airing of the Final as part of a "Television Continental Exchange" (Eurovision Network). Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 BBC Sport in Black and White detailing the launch of the Eurovision Network. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 BBC Sport video where Ray French recalled watching the coverage of the Final (video harnesses British Movietone newsreel). Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 BBC summarising early telerecordings prior to videotape. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Web Archive article discussing how most early television is missing due to the lack of directly recording television. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ BBC Genome Blog noting the recording of the 1949 football match between England and Italy. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 England Football Online summarising the BBC's usage of film recording, which preserved events like the 1953 FA Cup Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the original broadcast of the 1953 FA Cup Final. Retrieved 15th Sep '23

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the subsequent broadcast of the 1953 FA Cup Final as a telefilm. Retrieved 15th Sep '23