Birth Control (lost banned family planning documentary film; 1917)

Birth Control (also known as The New World) is an 1917 American semiautobiographical documentary film. Produced by and starring Margaret Sanger, it documented Sanger's career as a nurse and her controversial involvement in the early era of family planning in the United States. Presented in private showings between 10th April-6th May 1917, it was later banned in America before it was publicly distributed.

Background

Birth Control's originated from tragic circumstances.[1][2][3][4] Margaret Sanger was born in a family consisting of eleven children, with her mother also suffering seven miscarriages.[2][1] At age 19, she saw her mother pass away from tuberculosis.[2] Margaret would resent her father for contributing to the 18 pregnancies, which she felt played a part in her mother's death.[2] She also began studying nursing at the White Plains Hospital and the Manhattan Eye and Ear Clinic, eventually becoming a nurse at the Lower East Side of New York City.[2][1]

Sanger primarily visited working-class immigrant women who generally lacked knowledge and education regarding contraception.[2][1][3][4] This resulted in many, especially those suffering from poverty, experiencing unwanted pregnancies.[2][1] Back then, not only was abortion illegal in America, so too was accessing contraceptive information as per an 1873 legislative called the Comstock Act of 1873, which deemed the practice "obscene".[5][1][2][3][4] According to Sanger, several women she worked with had experienced multiple childbirths and miscarriages, with some also attempting illegal self-induced and back-alley abortions to avoid repeating fates.[1][2][3][4] One story Sanger frequently retold was of meeting "Sadie Sachs", a woman who had urgently requested contraceptive information from a doctor after carrying out a self-induced abortion.[3][4] The male doctor laughed and told her only abstinence from sex with her husband Jake could prevent pregnancy.[3][4] Abstinence was ultimately not an option, and Sachs passed away following a botched self-induced abortion she underwent before Sanger could meet her again.[3][4] Whether Sachs actually existed or was simply based on Sanger's experiences has been a subject of debate.[3]

Following the deaths and other harrowing experiences she witnessed, Sanger aimed to battle America's strict anti-contraceptive legislation, which were reinforced by anti-obscenity laws.[1][5][3] She produced the monthly newsletter The Woman Rebel, a publication focusing on women's rights, coining the term "birth control" and deeming it as a critical free-speech issue in the country.[1] She also established the United States' first birth control clinic on 16th October 1916.[6][7][8][1][2] Situated within Brownsville, Brooklyn, the clinic lasted just ten days before it was forcibly shut down, for Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne were quickly arrested for distributing contraceptives and maintaining a "public nuisance".[9][7][1][2]

Nevertheless, Sanger continued campaigning, including founding the American Birth Control League, which since 1942 is known as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.[7][2][1][8] She was also influential in the success of the Pill, deemed a critical invention for achieving safe and effective contraception.[10][2] A year before her death in 1966, the Comstock Act of 1873 was altered after the Griswold v. Connecticut case saw private contraceptive use be declared a constitutional right.[2][5] Sanger has been declared one of the pioneering figures of birth control and family planning across the United States.[1][2][8] Her legacy is not extended towards abortion rights, as Sanger believed the practice should only be used in emergencies and that contraception is the most practical solution to avoiding unwanted pregnancies.[11] Sanger has also faced contemporary criticism for her views on population control, eugenics, and race.[12][13][1][6] Others have claimed that Sanger's views were simply a product of the society she lived in, and no more extreme.[1] To date, contraception and abortion remain heated topics across the United States.[14][12]

Birth Control

Before serving 30 days in jail in 1917 for operating an illegal birth control clinic, Sanger decided to further her cause by producing a film, having been interested in art and fiction during her life.[15][9][4][8] Written by Sanger and The Birth Control Review founder Frederick A. Blossom,[16] Birth Control was part-documentary and part-narrative, with Sanger starring in a dramatized semibiographical account of her career within family planning.[17][9][15][8] She collaborated with the B.S. Moss Motion Picture Corporation to distribute the film, Moss himself sharing liberal values for the 1910s.[18][8]

The film is split into five reels; the first primarily consisted of Sanger being interviewed, with her discussing and defending her actions in fighting for birth control, stating that the Brownsville clinic served impoverished women instead of those enjoying good health and financial status.[19][8][18][15] Scenes incorporated during the interview featured large families consisting of "weak and crippled children of exhausted, poverty-stricken mothers" living within poor slum conditions.[8][19] Among the poor mothers featured included Helen Field, who would be based on Sachs.[18][19][4] The film also showcases better-off, smaller families, with the work pushing the narrative that this is the family unit to obtain.[8][19]

Birth Control also focused on Sanger's nursing career, and her difficulties in resisting the urge to inform her clients about contraception, lest she violate the Comstock law.[8][19] However, following Field's suffering and death, Sanger opts out of nursing and began her campaign for legal, adequate dissemination of birth control.[19][8][18][4] Following this, Sanger opens a birth control clinic in Brooklyn, providing critical contraceptive information to her main clientele, impoverished women.[8][19][18][4] The clinic proves a major success and the facility is crowded by women.[8][19] Sanger is eventually arrested for this, and the clinic is shut down.[9][19] However, the film concludes with Sanger campaigning onwards and expressing hope for the future of birth control.[9][19] The film contained propaganda elements, New York State Supreme Court judge Nathan Bijur stating that by presenting the client as filled with poor women seeking education on contraception, it implied that rich folk are actually breaking the law by accumulating contraceptive information and solutions that poorer people cannot.[8][19] Whether it contained Sanger's views on race and eugenics remains unclear.[20]

Private Showcases and Banning

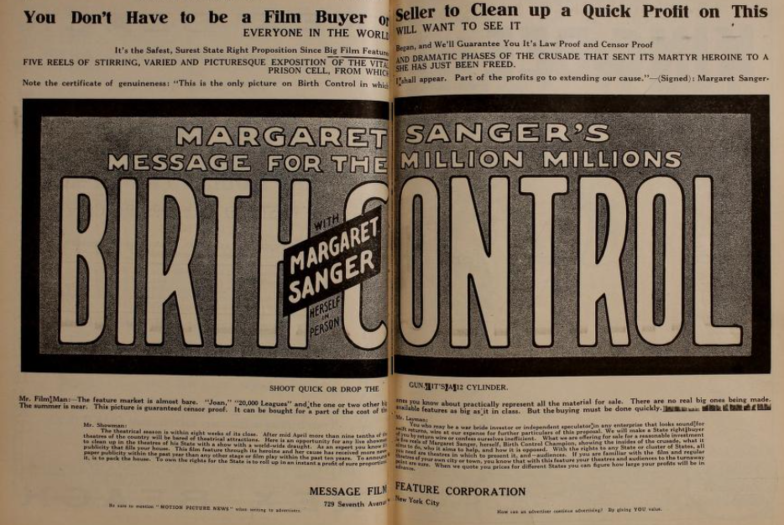

Despite her jail time delaying filming, Birth Control was eventually completed by April 1917.[21][18][4][15] It received promotions in publications such as the 21st April 1917 issue of Motion Picture News and The Moving Picture World, as well as in The New York Times.[22][23][9][18] The film's target audience was clear with the slogan "Every woman in the world will demand to see it" placed in one advertisement.[22] Another advertisement placed in Sanger's The Birth Control Review exclaimed it was "An honest birth control film at last!"[24][9] To avoid concerning exhibitors that later copycat films would be produced, Sanger declared her starring role in the film would be an exclusive.[15][22][23] She also promised to redistribute some of the profits to further the birth control campaign.[15][22][23][9] Seeing as the term "birth control" was controversial throughout much of America, the film was also set to be showcased under the title The New World, with the chosen title depending on the audience and exhibitor.[15][18][9]

According to Motion Picture News, the film was approved by the National Board of Reviews, who agreed no scenes needed to be censorship as the film appropriately handled its sensitive subject matter.[21][18] Likely because of this, advertisements also boasted the film was "Law Proof" and "Censor Proof".[18][22][23] Whereas some sources claim Birth Control was only privately showcased once on 6th May 1917, others note that the Message Photoplay Company, a subsidiary of the B.S. Moss Motion Picture Corporation, had begun privately exhibiting the film starting from 10th April at the Lyric Theatre on Broadway.[22][23][18][21][15] It would also be privately made available at the 42nd Street in New York City.[18] Sanger would additionally appear in-person to conduct a lecture detailing her career and spreading awareness of the Birth Control Society.[21][23][15] Following the Broadway engagement, Sanger and the film would tour nationwide to promote the family planning cause.[22][23][21]

The early private lectures were viewed by journalists and activists.[25][19] Among them included reviewers for The Moving Picture World and Variety.[19][25][18][9] In the 21st April 1917 issue of The Moving Picture World, praise was centred upon the film's strong handling of the subject matter, deeming that the pictures presented, including that of "the feminine keeper of public morals, and of the male parasite who seizes upon up more than a "tempest in a teapot" for the plenishing of his own purse", helped solidify an interesting narrative throughout the five reels.[19][18] It therefore recommended the film to primarily adult audiences.[19] Meanwhile, the 13th April 1917 issue of Variety focused primarily on Sanger's appearance in the film, declaring her portrayal as being extremely sincere and reflected that of "the same placid, clear eyed, rather young and certainly attractive propagandist that swayed crowds at her meetings and defied the police both before and after her incarceration."[25] The review likewise praised all actors featured for their realistic portrayals, and deemed the film will likely succeed in getting viewers to consider, and potentially change, their views on birth control.[25]

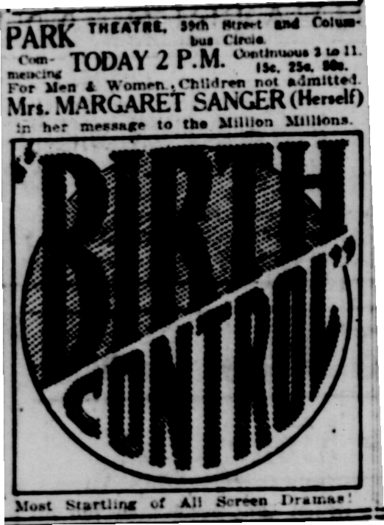

The final private showcasing occurred on 6th May 1917, in front of an estimated 200 people.[4][18][9] Following this, the film would seemingly receive its first public showcase at the Park Theatre in Manhattan.[9][4][18] The promotions were certainly successful in attracting an audience, as thousands would quickly line-up outside the theatre to view the film.[26][9] Little did they realise, the film had already been banned by the city's licence commissioner George Bell.[27][28][26][9][15][18] Bell had banned the work after he claimed numerous citizens had complained about it.[27] After a vote was conducted by the Brooklyn Branch of the Motion Picture Exhibitors' League, unanimous disapproval of the film was noted, supporting its banning.[27][18] Bell summarised his decision by stating a film on birth control should not be classified as theatrical entertainment.[27]

Appeals were launched against the ban, which reached the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court.[28][26][15][9] Among supporters included Supreme Court Judge Nathan Bijur.[28][8][9][15] However, the ban was ultimately upheld as per the 1915 Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, which prevented films from being protected through the First Amendment as the works were considered business instead of art.[28][9][15][8] Further, under the Code of Ordinances of the City of New York, productions could be censored or banned in the "interest of morality, decency and public safety and welfare."[28][9][15][18] Birth Control made dubious history by becoming the first film produced by a woman to be subsequently banned in the United States.[9]

Availability

By the time the Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio ruling was thrown out in 1952, thus making the film legal again, Birth Control was declared missing.[29][9][18][15][8] It is believed that all copies of the film were destroyed, with no footage having resurfaced despite several extensive searches conducted over the years.[9][29] Nevertheless, a few stills remain viewable, including as part of the Sophia Smith Collection and in The Birth Control Review advertisement.[17][24][29]

Gallery

Images

Video

External Link

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Britannica article on Sanger. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 PBS summarising the life and career of Sanger. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Margaret Sanger Papers Project summarising the story of Sachs and how it motivated Sanger's campaign. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Today in Civil Liberties History summarising the one instance Birth Control was showcased, before it was banned. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 The First Amendment Encyclopedia summarising the Comstock Act of 1873 and its negative influence on birth control. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Time detailing the controversies surrounding Sanger's views on eugenics and race. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Britannica detailing the history of Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 Feminist Current summarising the film and including the quote from Supreme Court judge Nathan Bijur regarding the film's content. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 Margaret Sanger Papers Project summarising the filming of Birth Control and its banning. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ History detailing the establishment of the Pill. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ Sixth edition of Family Limitation where Sanger summarised her views on abortion (p. 5) Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 USA Today's Kristan Hawkins' opinion on Sanger and the heated debates over her legacy and abortion. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ The New York Times' Alexis McGill Johnson's opinion piece on Sanger. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ National Geographic detailing the history of abortion and contraception in the United States, which remain heated topics as of the present day. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 American Film Cycle summarising the film, its private showcases, and its eventual banning. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ The New York Times detailing the life and career of Blossom. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 A History of the Birth Control Movement summarising the film and its writers, and providing a photo from the Sophia Smith Collection. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 18.14 18.15 18.16 18.17 18.18 18.19 American Film Institute listing of the film. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 21st April 1917 issue of The Moving Picture World reviewing the film. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ The Black Stork noting the lack of information surrounding whether the film contains views on eugenics. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21st April 1917 issue of Motion Picture News reporting the film was approved and set for a national release following a Broadway showcase. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 21st April 1917 of The Moving Picture World promoting the film. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 21st April 1917 of Motion Picture News promoting the film. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 April-May 1917 issue of The Birth Control Review promoting the film and containing two stills of it. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 13th April 1917 issue of Variety reviewing the film. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Rhetorics of Motherhood summarising the film's strong marketing that led to thousands seeking to attend, only for a ban to be upheld. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 19th May 1917 issue of The Moving Picture World reporting on the film being banned by Bell. Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Summary of the Message Photo-Play Co., Inc. v. Bell Retrieved 19th Mar '23

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Woman of Valor declaring that all copies of the film were destroyed, but noting a few film stills exist. Retrieved 19th Mar '23