Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey (partially lost radio coverage of "The Long Count Fight"; 1927)

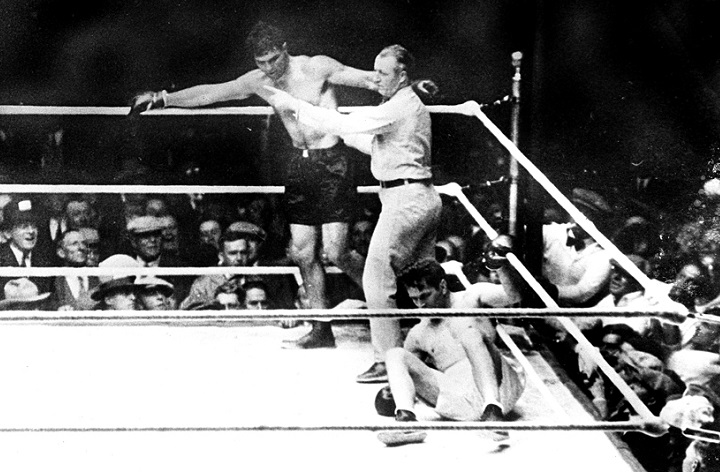

Referee Dave Barry orders Dempsey to retreat to a neutral corner, the delay in count giving Tunney extra seconds to recover.

Status: Partially Lost

On 22nd September 1927, Gene Tunney defended his World Heavyweight Championship against Jack Dempsey at Soldier Field. In a rematch of their 1926 encounter, Tunney would again become victorious by decision. The match is nicknamed "The Long Count Fight", so-called because Dempsey, during a seventh round knockdown on Tunney, took extra time retreating to a neutral corner and thus gave the champion precious additional seconds to recover. It also marked Dempsey's final professional match. This encounter was also broadcast live on radio from NBC; it is notably the oldest boxing match with surviving radio coverage, although some of the broadcast has ultimately become permanently lost.

Background

The encounter was a rematch that originally occurred on 23rd September 1926.[1][2] In that match, Dempsey was the champion, having defeated Jess Willard on 4th July 1919 for the belt.[3][4][1] Tunney however would dominate the ten-round match, winning the belt by decision.[5][6][7][2][1][4][3] While Dempsey considered retiring following the loss, he nevertheless carried on.[8] In a match for a title shot against Tunney, Dempsey beat Jack Sharkey on 21st July 1927, when following Sharkey complaining to the referee alleging Dempsey had been hitting below the belt, Dempsey landed a left hook on his foe's chin for the KO win.[9][4][3][8] Heading into the Tunney-Dempsey rematch, Tunney had not fought another professional match.[5][6] Under normal circumstances, he would have received support from the crowd, primarily because he fought in the First World War as part of the US Marine Corps, even being nicknamed "The Fighting Marine".[7][6] By contrast, Dempsey was still facing controversy for alleged draft-dodging, something that also plagued him during his win over Georges Carpentier in 1922.[10][2] However, the American public never really warmed to Tunney; this may have been for several reasons, including for his private, perhaps too overly-successful image, and for a rise in popularity for Dempsey during this time period.[2][7]

Meanwhile, a concern for Dempsey arose; word got out that notorious gangster Al Capone was a major fan of Dempsey, and wanted him to regain the championship.[11][2][8] Capone also allegedly bet $45,000 on a Dempsey win, with rumours apparent he was seeking to help fix the match in Dempsey's favour.[2][11][8] To avoid possible match-fixing, referee Davey Miller was replaced with Dave Barry, following rumours that his brother had bet $50,000 on a Dempsey win.[2][11][8] Nevertheless, Dempsey was widely considered the favourite to win, most likely because of the betting going on.[2] Since the Dempsey-Carpentier encounter, radio coverage had exploded in popularity, establishing a Golden Age.[12][2] The NBC Red and Blue Networks were on-hand to cover the match, with commentary provided by Graham MacNamee and Phillips Carlin.[13][14][15][2] Millions across the country tuned in to listen to the broadcast, McNamee's play-by-play proving to further amplify the bout's intensity.[14][15] Reports indicated that up to ten radio listeners may have died from heart attacks during the airing of the fight.[15][14] In a review by Sports Illustrated, McNamee was praised for his engagement and intensity, though did criticise him for overly-described everything, and not always in an accurate fashion.[15]

The Fight

The fight drew 104,943 at Soldier Field, generating a $2,658,660 gate.[16][11][2] This meant it became the first of any entertainment platform to break the $2 million mark.[16][11][2] Overall, Tunney had greatly controlled the opening five rounds.[11][2][8] Aside from reflecting their previous bout, Tunney's dominance may well have been boosted by the ring being 20 feet instead of 16.[11][2] This benefitted Tunney, as he generally won matches via his fancy footwork and boxing from a distance, whereas Dempsey often aimed to crowd his opponents stuck within a smaller ring.[11] In the sixth round, the challenger fought back, winning the round by closing the distance.[11] But in the seventh round, as Tunney slowed down, Dempsey finally managed to trap Tunney against the ropes via a left punch.[11] He capitalised with a barrage of blows, which secured a knockdown.[11][2][8]

While the champion was down, Dempsey stood still and looked down at his foe, a common tactic he used so he could immediately attack should his opponent recover in time.[4][5][11][2] What Dempsey did not realise was that a series of rule changes from the Illinois State Athletic Commission, actually requested from his camp, meant this was no longer allowed.[2][11][4][5] A new rule indicated that should a knockdown occur, a boxer must retreat to a neutral corner, which is when a referee can then start the count.[2][11][8][4][5] Barry tried to get Dempsey to conform, but the latter remained still.[2][11][8][4][5] Finally, Dempsey complied, with at least 3-5 seconds having elapsed by the time he moved to the corner.[2][11][8][4][5] Barry then started the count, with Tunney getting up at nine.[17][2][11][8][4][5] Years after the match, Tunney insisted that he actually could have gotten up at two, but enabled himself time to recuperate by delaying himself getting to his feet.[17] Dempsey firmly believed this was the case, although this was initially not enough to placate many viewers who believed Dempsey should have won via KO at that point, and were angered Tunney was allowed ample time to recover.[17][11][2] The public release of a film of the match has since been analysed numerous times to determine the legitimacy of the count, the encounter being nicknamed "The Long Count Fight" because of the controversy.[11][4][5]

In the eighth round, things were again business as usual, with Tunney regaining his stance as Dempsey began to tire.[2][11][8] He managed to achieve a knockdown, which also became controversial as the referee could be seen immediately counting Dempsey before Tunney had retreated to a neutral corner.[11][2][8] Dempsey recovered, but was unable to prevent Tunney from controlling proceedings for the remaining rounds.[2][11] Tunney was therefore declared the winner by decision, a result Dempsey graciously accepted, telling Tunney upon raising his hand "You were best. You fought a smart fight, kid."[18][11][2][8][4][5] Despite this, an appeal was lodged to the Illinois State Athletic Commission alleging Barry's count was improper.[2] Despite Barry seemingly not conform to the rules written by the Commission, the subsequent ruling was in favour of Tunney.[2] Dempsey retired from professional boxing following this rematch, and retired from exhibitions in 1940.[4][3][8][11][2] Meanwhile, Tunney competed in one further fight, defending his World Heavyweight Championship against Tom Heeney on 26th July 1928.[5][6][2][8] After winning the bout by TKO, Tunney also retired from professional boxing.[5][6][2][8] He was never defeated by KO, and lost only one match, to Harry Greb on 23rd May 1922.[5][6]

Availability

Under normal circumstances, a radio broadcast from the 1920s would not have survived, as recordings seldom occurred.[19] Outside sporting broadcasts were especially tough to record, as recording discs generally were impractical and typically only captured a few minutes of content.[19][14] In fact, NBC did not record either of its Tunney-Dempsey broadcasts, meaning the coverage of their original encounter is lost forever.[14] However, the Long Count Fight was substantially luckier when it came to preservation.[14][13] While no official recording emerged, it is known that a pirate recording of the broadcast occurred.[14][13] A small blues record label company in Wisconsin called Paramount (not to be confused with the large production company of the same name) had borrowed the disc recording equipment, and captured the coverage into ten 78RPM recording discs.[14][13]

Some copies were made and distributed, but they were not especially a financial success.[14][13] There may have been a few reasons for this; firstly, Paramount's recordings were questionable at best, with compromised sound quality indicating that the recordings consisted of Paramount placing a microphone next to a radio that was providing the coverage, renting facilities within Chicago itself to cut the audio.[14][13] Additionally, the coverage for each round starts and finishes abruptly, with the between-rounds commentary having not been recorded and presumably being lost permanently.[13][14] These recordings became some of Paramount's rarest, but most have since been recovered and publicly released.[13][14] According to early radio historian Elizabeth McLeod, a full disc collection was in the hands of a private collector, the only known collection still to exist.[13][14] As of the present day, about 32 minutes of audio can be publicly listened to.

Gallery

Videos

See Also

- Barbara Buttrick vs Gloria Adams (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1959)

- Bill Lewis vs Freddie Baxter and Archie Sexton vs Laurie Raiteri (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1933)

- Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- England vs Ireland (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1937)

- Exhibition Boxing Bouts (lost early television coverage of boxing matches; 1931-1932)

- Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)

- Heavyweight Champ (lost SEGA arcade boxing game; 1976)

- Jack Dempsey vs Billy Miske (lost radio report of boxing match; 1920)

- Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Jo-Ann Hagen vs Barbara Buttrick (lost radio and television coverage of boxing match; 1954)

- Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Leonard-Cushing Fight (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- Rocky (lost deleted scenes of boxing drama film; 1976)

- Uncle Slam and Uncle Slam Vice Squad (lost iOS presidential boxing games; 2011)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Philly History detailing the 23rd September 1926 match. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 Sports Illustrated providing a detailed account of the Long Count Fight, including the prelude and the match itself. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 International Boxing Hall of Fame summarising Dempsey's career. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 BoxRec detailing Dempsey's fight record. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 BoxRec detailing Tunney's fight record. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 International Boxing Hall of Fame summarising Tunney's career. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 The Fight City detailing Tunney's career, him facing indifference from the American public, and his matches with Dempsey. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 Archived History summarising the match. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ Boxing News Online detailing the Dempsey-Sharkey match. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ The Fight City detailing Dempsey's win over Carpentier and facing accusations of draft-dodging. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 East Side Boxing detailing the match, including Capone's rumoured involvement, the rule changes, and the match itself. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ The Golden Age of Boxing on Radio and Television detailing the rise of radio boxing coverage following the Dempsey-Carpentier fight. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 Documenting Early Radio detailing the Paramount recording, its limitations, and the full tape collection that has yet to be publicly released. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 Boxing Noir detailing NBC's coverage of the match, and a recording of it. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Sports Illustrated review of MacNamee's coverage. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Irish Boxing noting the match was the first in entertainment history to drew a $2 million gate. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Tunney detailing Tunney's reasoning for getting up at the count of nine. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ Box Raw summarising Dempsey's post-match comment to Tunney. Retrieved 1st Jan '23

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ngā Taonga noting most early-1920s sports airings were never recorded. Retrieved 1st Jan '23