The Boat Race 1949 (partially found footage of rowing race; 1949)

The Boat Race 1949 marked the 95th running of Britain's most prestigious side-by-side rowing event, which pitted defending champions the University of Cambridge against the University of Oxford. It occurred at the Thames' Championship Course on 26th March and saw Cambridge narrowly edge out Oxford by a 1⁄4 length to claim its third consecutive victory and increase the overall standings to 51-43 in its favour. This event marked another major media milestone in the sport's history, as it became the first Boat Race to be fully televised live.

Background

The 1949 edition of the Boat Race was the fourth staging of the event since the Second World War's end.[1] Indeed, World War 2 was the last time the race suffered a major break before the next edition.[2][1] With the exception of 2020's cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic,[3] the Boat Race has always since been hosted annually primarily at the River Thames' 4.2 mile Championship Course.[4][5][1] The event also marked 120 years since the first Boat Race of 1829.[6][1] Since then, the rivalry between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intensified, making it the must-win event for both teams.[7] Cambridge currently held the bragging rights; not only had they won the previous two editions, but they also led 50-43 in the overall standings.[1] It helped greatly that they maintained an undefeated record from 1924 to 1936.[1]

However, Oxford notably won the 1938 race,[1] the first time the Boat Race was televised in any capacity.[8][9] The BBC had also covered the 1939, 1947 and 1948 races.[10][11] However, due to technical limitations at the time, actual race coverage was frustratingly limited to just the start and finish.[12] The rest of the broadcast simply consisted of the radio broadcast from John Snagge with an animated chart detailing the positions of each boat.[12][9][11] The BBC had hoped to enhance its coverage in 1948 via a helicopter to capture live aerial shots, but the idea never prompted any experimental runs.[11] Instead, the corporation, led by Head of Outside Broadcast Unit Philip Dorté and sports broadcaster and executive Peter Dimmock, began planning with the Engineering Division on a more conventional approach.[6][11]

The Broadcast

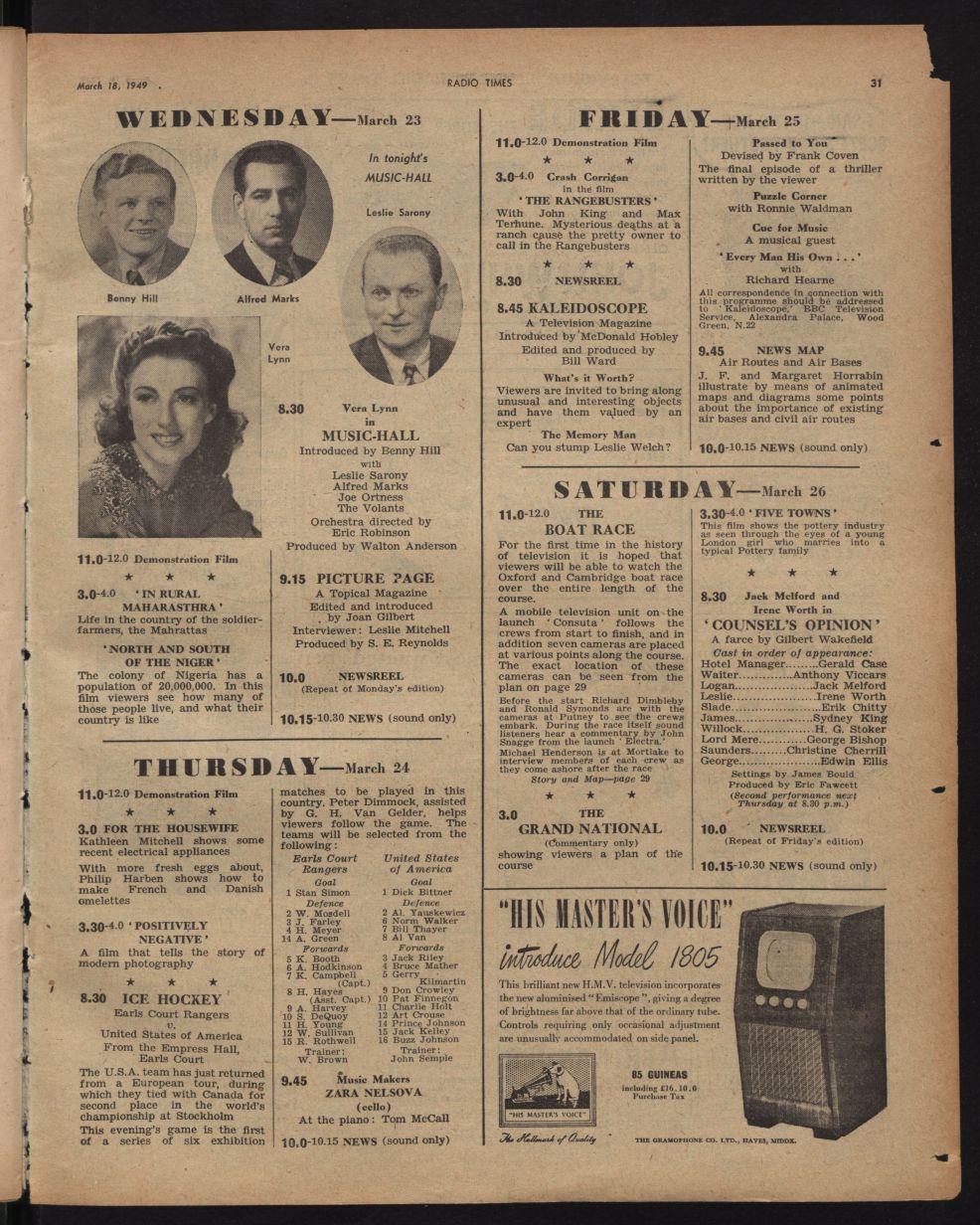

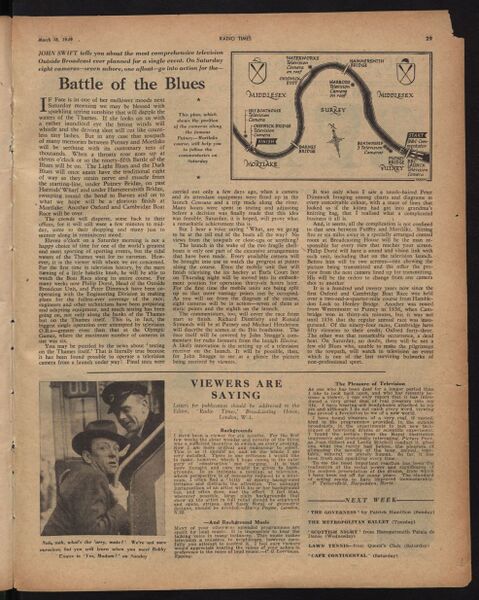

A consensus emerged that every BBC mobile unit would be required to televise the 1949 race.[6][11] Unlike in previous events where cameras were simply placed at Putney (the start) and Mortlake (the finish), seven were instead transferred to strategic locations.[6] At Putney, three cameras were placed for Richard Dimbledy and Ronald Symonds' opening presentation, to capture footage of the crews leaving the boathouses and entering the Thames, and to cover the race start.[13][14][6][11] The BBC then gained permission to place cameras on the roofs of Harrods and the Waterworks, so that footage could be shown as the rowers passed Hammersmith Bridge and Chiswick Eyot respectively.[6] Finally, two cameras were at Mortlake; one captured the finish while the other was used for Michael Henderson's post-race coverage at the Ibis boathouse.[6][13][14] Already, the broadcast plans were noted by Radio Times' John Swift as a majorly ambitious endeavour, especially as the 1948 Summer Olympics broadcasts only harnessed six cameras throughout its duration.[15][6] Days before the event, it was decided that another camera at Harrods was needed, bringing the total units to eight.[16][9][11][8]

But even so, this plan as it stood would only cover parts of the race.[6] The biggest challenge was the incorporation of a waterborne Marconi Mk 1, which aimed to fully capture the entire event.[16][11][6] It was placed on the bow of Consuta, one of several launch boats that would follow the action from behind the rowers.[17][6][16] The main dilemma was figuring out how to relay the coverage from the Thames back to the BBC Broadcasting House at Alexandra Palace.[11] According to BBC engineer Ron Chown, as the Sutton Coldfield transmitter station was nearing completion but would not officially open until December 1949,[18] its full frequency was available and consequently utilised to establish a potent link.[11] An oscilloscope would then transmit the signal to the closest of the eight mobile units, which would subsequently relay it back to the Broadcasting House.[11] According to Dorté in a BBC newsreel interview, the signal would be received at Harrods, then Waterworks and finally somewhere near Chiswick.[19] Dorté was also the broadcast's director and he had simultaneous access to the current television output and the "preview" footage from the next camera in syndication.[6] To achieve a sufficient connection between the units and Alexandra Palace, the BBC relied on residents for permission to use their telephone lines.[11]

Dimbledy and Symonds provided exclusive television commentary for the start, while Henderson did the same for the finish.[13][14][11] However, John Snagge worked double duty throughout much of the event as his radio commentary on sister launch Electra was linked to the television broadcast.[6][11][13][14] Considering the broadcast's complexity, the BBC carried out extensive testing at the Thames days before the event.[6] After some teething issues, the experiments objectively proved that footage could indeed be sufficiently captured and transmitted from Consuta.[19][6] The broadcast was predicted to attract around 750,000 viewers.[20] What analysts did not anticipate was that, amazingly, the coverage would also reach Cape Town in South Africa.[21][22] It was one of several freak instances where a television signal got redirected off the ionosphere by sunspots, exceptionally boosting its range.[23] It became a case study for mathematical theories attempting to explain the phenomena.[22][21]

From a technical standpoint, the broadcast was a big success.[11] However, both it and the radio broadcast were impacted when Electra suffered an engine failure just prior to Hammersmith Bridge.[24][8] Snagge tried his best to carry on, but it proved virtually impossible as the rowers were side-by-side throughout the end stages,[25] with Electra unable to close the ever-increasing gap for the final two miles.[8][24] Passionate regardless, he uttered during the finish, "I don't know who's ahead it's either Oxford or Cambridge".[26][24][8] Naturally, it became one of Britain's most famous sports commentary gaffes.[24][8] It is also possible the broadcast was affected by talkback, caused by communication between Alexandra Palace's sound transmitter and Consuta's crew.[11] Further, it is likely a temporary blackout occurred once the boat went under the bridges.[19] But Electra's failure aside, the airing generated excitement among BBC engineers concerning the future, with superintendent engineer D.C. Birkinshaw encouraging them to find new means of improvement.[11][19] The 1950 edition saw exclusive television commentary and two cameras placed on the replacement launch Everest.[27][11] Consuta was nevertheless still harnessed for future Boat Race coverage until 1969.[17]

The Race

For the Cambridge (Light Blues) crew, Antony Rowe was selected as its President.[28] Rowe had competed at the London Olympics in the single sculls event but was knocked out in the Semi-Finals.[29] In contrast, the Oxford (Dark Blues) President was Paul Bircher, who along with teammates Brian Lloyd and Paul Massey won silver at the coxed eights, behind the then-untouchable United States.[30][28] This Olympics success likely convinced some newspapers and newsreels that the Dark Blues were the slight favourites for the event.[31][20] The Light Blues were, however, deemed to have an overall strength advantage.[31][25] Meanwhile, Guy Oliver Nickalls became the race umpire.[32] Aside from leading the Oxford crew to glory at the 1923 event, he was also a commentator for the first Boat Race to receive live radio coverage.[33] Both crews' rigorous training exercises were filmed by British Pathé in Henley, Oxfordshire.[34][35]

Race preparations began at 11 am on 26th March.[14] According to Swift, this unusual timeslot was chosen to reflect the tidal changes of the Thames.[6] Ultimately, it proved a wise decision as the race occurred in ideal racing conditions.[25][31] Oxford, having won the toss, were given the choice of the starting positions.[36][25] They opted to put Cambridge on the Surrey side, leaving them with the seemingly more ideal Middlesex bank.[37][36][25] After both crews made strong starts, it was Oxford who initially gained a half-length upper hand thanks to achieving 36 strokes per minute compared to the Light Blues' 35, with their stroke Chris Davidge having neutralised initial Cambridge attacks.[25][31][37] Following a successful navigation of the Fulham Bend, the Dark Blues gained a 1.5-length lead over the Light Blues at the Mile Post.[25] Cambridge was only just able to prevent Oxford from crossing over to its waters.[36] As the race progressed, Davidge was again praised by British Pathé for maintaining this gap as the boats went under Hammersmith Bridge.[31][25][37] Even though Cambridge did outperform Oxford at the Surrey Bend, the crew was still a length away as the boats passed Chiswick Steps.[25][36]

However, two factors were soon at play; Cambridge's aforementioned strength advantage and the Dark Blues' fatigue following their Surrey Bend defence.[25][36] The Light Blues began a powerful comeback at Duke's Meadows, something Davidge could do little to stop.[25] As the boats reached Barnes Bridge, Oxford held a tiny lead with just one bend before the finish.[31][25][37][36] If there was a crumb of comfort for Oxford, it was that the Middlesex side had always previously won if they were ahead at Barnes Bridge.[36][31] Subsequently, Oxford reportedly gained the better side of the final bend.[25] But a determined Cambridge upped their pace, resulting in a side-by-side final dash to Chiswick Bridge.[31][37][25][36] When considering this and Electra's engine failure, it is entirely understandable why Snagge could not determine who led at the finish.[24][8] Indeed, the boats were separated by just a quarter-length, with Cambridge having prevailed for their third consecutive Boat Race win.[36][37][31][25][1]

At the time the 1949 Boat Race's quarter-length finish was the closest result to have a decisive winner.[1][36] Only one race resulted in a literal photo finish: the famous dead heat of 1877.[36][37][1] Since then, other close results have been recorded, including Oxford's 2003 win by a mere foot.[1] The 1949 event took 18 minutes and 57 seconds and received major acclaim from various publications.[25][36][31][37] British Pathé coined it "the Boat Race of the century".[31] With this victory, Cambridge extended their overall lead to 51-43.[1] Dark Blues misfortune allowed Cambridge to win the 1950 and 1951 editions, before Oxford finally achieved glory again in the 1952 race.[36][1]

Availability

The Boat Race 1949 notably became one of the first live BBC programmes subject to a telerecording, where the broadcast was filmed off-screen by a dedicated television recording camera like the Moy-Cintel 35 mm.[38][39][40] During that period, very few live broadcasts were preserved.[41][38][40] Even then, only a few clips from the Opening Ceremony of the 1948 Summer Olympics and the England-Italy football match of 30th November 1949 were actually captured.[42] The experimental nature of early telerecording therefore makes it unclear whether the near-19-minute race was recorded in its entirety.[40] Some sources claim the telerecording was shown on television that same evening.[39][40] However, neither Issue 1,327 nor 1,328 of Radio Times list this anywhere in their television summaries.[43][14][13]

If the recording still exists, it has not been made publicly available by either the BBC or British Film Institute.[44][45] The BBC Archive has released a newsreel reporting on the plans to fully televise the race live, which was televised on 21st March 1949.[46][19] Additionally, British Pathé and Gaumont British News newsreels of the event have also been made publicly available.[31][37] This also includes the training sessions recorded by the former.[34][35] Additionally, exceptionally rare colour footage of the race was preserved by Kinolibrary and Bridgeman Images.[47][48] Photos of how the television broadcast commenced can also be located online.[49][16]

Gallery

Videos

Images

See Also

- The Boat Race (partially found television coverage of rowing races; 1938-present)

- The Boat Race 1927 (lost radio coverage of rowing race; 1927)

- The Boat Race 1938 (partially found footage of rowing race; 1938)

- The Oxford and Cambridge University Boat Race (lost footage of rowing race; 1895)

External Links

- GA-Class Wikipedia article on the Boat Race 1949.

- Excerpt from Snagge's radio broadcast and his famous gaffe.

- IMDB page for the Boat Race 1949.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 The Boat Race providing a list of Boat Race results. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Hear the Boat Sing summarising the unofficial races that transpired during World War 2. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Varsity reporting on the 2020 race's cancellation. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ The Telegraph summarising the history and prestige of the Boat Race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ The Boat Race detailing the Championship Course. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 Issue 1,327 of Radio Times previewing the race and its television coverage. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Cambridgeshire Live summarising the importance of the race for both universities. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 BBC summarising the history and milestones of Boat Race media. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Science and Media Museum summarising the broadcasts of 1938 and 1949. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues listing the earliest broadcasts of the Boat Race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 TV Outside Broadcast History detailing how the 1949 Boat Race broadcast was achieved. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Issue 1,275 of Radio Times summarising the limited coverage of the 1948 Boat Race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 BBC Genome archive of Radio Times issues detailing the broadcast of the race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Issue 1,327 of Radio Times listing the race coverage. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC on how the 1948 Summer Olympics broadcasts were conducted. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Transdiffusion noting the extent of cameras used for the event, including the Consulta camera. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 National Historic Ships detailing the history of Consuta. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC detailing the unveiling of the Sutton Coldfield transmitter station. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 BBC Newsreel film regarding the ambitious broadcast. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 26th March 1949 issue of the Daily Mirror (Sydney) reporting on the upcoming broadcast and being expected to attract 750,000 viewers. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Journal of the National Bureau of Standards using the freak South African transmission during its section on "Attenuation of the Waves Around a Curved Earth". Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Journal of the National Bureau of Standards summarising the unusual transmission in South Africa and a mathematical theory used to explain the phenomena. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Dusty Old Thing summarising the phenomena which allowed the broadcast to reach South Africa. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Independent summarising the legacy of Snagge's line. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 25.11 25.12 25.13 25.14 25.15 Archived The Boat Race report on the race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Radio Moments providing the excerpt from Snagge's broadcast containing his famous gaffe. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Whirligig summarising the improvements made for the 1950 Boat Race broadcast. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race listing the Presidents for each crew (p.g. 50-52). Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Archived Sports Reference noting Rowe was knocked out in the Semi-Finals at the London Olympics' single sculls event. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Archived Sports Reference detailing the results of the Coxed Eights at the London Games. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 31.00 31.01 31.02 31.03 31.04 31.05 31.06 31.07 31.08 31.09 31.10 31.11 British Pathé newsreel of the race Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race noting Nickalls was the race umpire. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Olympedia page on Guy Oliver Nickalls. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 British Pathé footage of Cambridge's training sessions. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 British Pathé footage of Oxford's training sessions. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 36.00 36.01 36.02 36.03 36.04 36.05 36.06 36.07 36.08 36.09 36.10 36.11 36.12 One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race providing a brief race report. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 37.8 Gaumont British News newsreel of the race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Restoring Baird's Image noting the race broadcast was one of the first subject to a telerecording by the BBC. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Television and Consumer Culture: Britain and the Transformation of Modernity noting that the broadcast was subject to a telerecording shown later that evening. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume IV: Sound and Vision noting that the broadcast was subject to a telerecording shown later that evening. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Web Archive article discussing how most early television is missing due to the lack of directly recording television. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC Genome Blog summarising the early and brief recordings of the 1948 Summer Olympics and the England-Italy football match. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Issue 1,328 of Radio Times television listings which does not cite any telerecording of the 1949 Boat Race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC Archive listings of all available Boat Race media as part of its Archive Downloader. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ British Film Institute listing media related to the 1949 Boat Race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ BBC Archive summarising the BBC newsreel film, titled "The logistics of televising the Boat Race". Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Kinolibrary providing rare colour of the race. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Bridgeman Images listing of the colour footage. Retrieved 19th Jan '24

- ↑ Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide providing photos of the television process. Retrieved 19th Jan '24