Albert Brighton (lost footage of fatal filming accident; 1911)

On 11th July 1911, actor Albert Brighton was filming a scene for an upcoming Belmar Photoplay Company production. It occurred at Brady's Pond in Staten Island and involved him rescuing a damsel in distress trapped in the water. However, Brighton met a tragic end when he got into difficulties while swimming to her location, where he eventually drowned. His final moments were captured on a Belmar camera. In a move that generated scorn from the mainstream newspapers and film industry trade journals, Belmar publicly screened Brighton's drowning and the failed rescue attempts.

Background

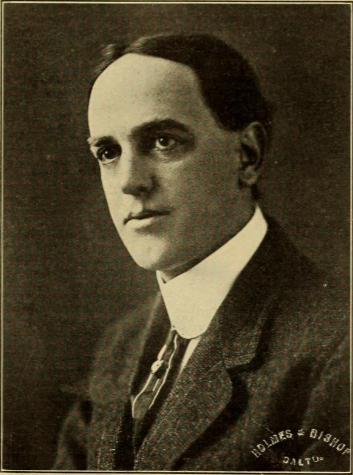

Before working for the Belmar Photoplay Company (also known as the Henry Belmar Moving Picture Company), 35-year-old Albert Brighton had enjoyed a long theatrical and film career.[1][2][3] First starting out in Edison films, Brighton achieved his biggest hits with the Nestor Company. According to the 22nd July 1911 issue of The Moving Picture World, some of Brighton's prominent films included At Cedar Ridge, At Panther Creek, Sleepy Hollow and The Bridal Trail. His main starring roles were in Western dramas and comedies, with The Moving Picture World stating he excelled in portraying "rugged heroism".[1] Additionally, Brighton had been a member of the Ben Greet players.[1][2] In June 1911, Brighton decided to work for Belmar.[3][1] Six months prior, he had married his partner in New York.[2][1]

Brighton's latest project was a drama located at Brady's Pond in the Grassmere region of Staten Island.[4][1][3] He was set to film a chase sequence where his character and a black slave pursued the villain via boat, the latter having kidnapped the main protagonist's wife and child.[4] Brighton had reportedly tested the water beforehand and was satisfied with its current depth.[2] The actor was considered a very strong swimmer, leaving Belmar unconcerned over the scene's recording.[5][3][4] As the sequence was being filmed, around 50-60 people observed the scenes at a nearby restaurant.[2] Others watched at the pond's banks.[1][5]

The Drowning

In the first scene, Brighton and his slave caught up to the villain's boat. However, the villain suddenly used an oar to shove Brighton into the water. The slave subsequently dived in to rescue Brighton, who assured him he was alright. The slave had his own issues in the pond, as his shirt fell down and pinned his arms. This forced him to float as he could no longer swim.[4] The second scene took place 75 feet away, where Brighton was to rescue his wife. Some sources claimed she was portrayed by Mary Murray,[1][3] but the 17th July 1911 issue of The New York Times insisted Henry Belmar's wife, Laurel Love,[6] performed the role.[4] The New York Times also contradicted claims Love began the scene in the water after being thrown in by the villain,[7][1][3] reporting instead that she was trapped on a boat awaiting rescue.[4]

Brighton swam just under 15 feet before he abruptly stopped.[4] Suddenly, Love and others could see and hear Brighton frantically seeking assistance and throwing his arms up in desperation.[4][3][7] It is unclear why the actor stopped swimming. Some sources reported he might have suffered cramps and heat exhaustion as he swam through strong currents.[7][5][4] Other reports spoke of him possibly getting caught in quicksand or a mud bank.[1][2][3] In contrast to the media stereotype, wet quicksand cannot pull a human completely under. However, it can trap an individual in place as the water current overwhelms them.[8] Not a single individual initially intervened; in an interview with The New York Times, Belmar and Love admitted they thought Brighton was merely acting.[4] Meanwhile, the crowd applauded Brighton, assuming he was pretending to struggle in an attempt to make the film more realistic.[5][4][7] Brighton barely kept his head above water as he begged for help. Eventually, he sank a third time and ultimately did not resurface.[5][3]

It was only then that onlookers realised Brighton was not acting.[4][5][1] Belmar subsequently ordered some of his black personnel to dive in and rescue the actor, to which they all refused. Indeed, this would have caused a much bigger tragedy as none of them could reportedly swim.[4] Instead, Matty Middleton and Mr Kerrington either leapt into the water or rowed a boat into the vicinity.[4][1] Middleton managed to grab Brighton's hair, but only succeeded in picking off his player's toupee.[4] Other swimmers tried valiantly to retrieve the stricken actor, all to no avail.[3][2] Meanwhile, Love went ashore, rescuing the slave actor in the process.[4][7][2] Middleton suffered extreme fatigue once he returned to shore.[4] The camera was rolling throughout Brighton's drowning and the rescue attempts, capturing at least one hundred feet of footage.[4][3][2]

Eventually, Belmar abandoned their rescue operation and contacted Tompkinsville police. Brighton reportedly drowned at 1:30 am; it took until 7 pm before police recovered his body, dredging through the mud with grappling irons.[1][3] Brighton's death received national and international coverage,[4] including in Australia and the United Kingdom.[9][2] The Moving Picture World paid tribute to Brighton and insisted his legacy would be preserved via his appearances in motion pictures.[1] Brighton was buried in Minnesota, his mother having bared the full funeral expenses.[10][4]

Release of the Footage

Following the loss of his star actor, Belmar faced a dilemma concerning the production's future. In an interview with The New York Times, Belmar stated he strongly considered cancelling the film before eventually deciding to replace Brighton with another actor.[4] However, after having exhausted a camera's entire roll of film capturing the tragedy,[2] as well as noting the extensive newspaper coverage surrounding it, Belmar made the controversial decision to publicly screen Brighton's final moments.[4][10] A promotion boasted that the film was 1,000 feet long, contained 41 scenes and featured one hundred actors. It promised to showcase Brighton's final moments and exclaimed how his reputation as a convincing actor was ultimately what led to his drowning in front of applauding spectators. Oddly, the advertisement did not list the work's title.[4]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the decision to commercialise the footage was widely condemned.[11][10][4] A New York Times reporter accused the move of being "cold-blooded", which Belmar admittedly agreed with. However, Love added that their company would never have screened the footage if Brighton had perished from an "unusually risky" stunt. Because Brighton had swimming credentials, the scene was deemed of lower concern. Somehow, this convinced Belmar and Love that publicly airing Brighton's drowning was therefore acceptable.[4] Film industry trade journals like The Moving Picture World and The Motion Picture Story Magazine were more scathing.[10][11] In its 29th July 1911 issue, The Moving Picture World refused to review the film. It asserted that while Belmar had the legal right to screen the event, his move to financially benefit from an accidental death was "inhuman". The publication also lambasted the Morning Telegraph for agreeing to publish the "atrocious advertisement".[10]

The Moving Picture World encouraged theatres not to exhibit the film.[10] It appeared most reciprocated the journal's outage; in response to a query by J. T. Pennington, the November 1911 issue of The Motion Picture Story Magazine stated it lacked knowledge of any cinema that proved willing to screen the "ghastly" footage.[11] Belmar continued in the film industry until 1918.[12] A disastrous production focusing on the life of Abraham Lincoln caused Belmar to accumulate major debts and suffer mental health issues.[13][12][6] He subsequently retreated to New Castle, Pennsylvania, where he sold trouser presses until his death in 1931.[12]

Availability

Brighton's death was routinely cited in newspapers that documented early accidents in filmmaking.[14][15][16] However, likely stemming from the subsequent film's poor commercial reception,[11] combined with the collapse of the Belmar Photoplay Company,[12] this early fatal filming accident has since fallen into obscurity. The footage is now believed to be lost and is likely among an estimated 80-90% permanently missing pre-1929 silent films.[17][18] Further evidence comes from the infamy of available early death footage, including that of Franz Karl Reichelt and Emily Davison,[19] which Brighton likely would have received if his final moments were preserved. No photographs are known to exist of the incident.

Gallery

Image

See Also

- Across the Border (lost silent western film and footage of fatal filming accident; 1914)

- Banned Film Festival (partially found film festival movies; date unknown)

- The Crow (lost Brandon Lee death footage from dark fantasy superhero film; 1993)

- Drowning Scene at Rockaway (lost film of alleged legitimate drowning accident; 1897)

- M. Otreps (lost footage of fatal filming accident; 1909)

- Midnight Rider (partially found unfinished biographical film based on band; 2013-2014)

- Mitr Chaibancha (lost death footage of Thai actor; 1970)

- Noah's Ark (partially lost film based on Bible story; 1928)

- The Skywayman (lost action drama film and death footage of stunt pilots; 1920)

- Underground (lost ITV teleplay broadcast; 1958)

- Wilhelm Zeitz (lost footage of fatal filming accident; 1907)

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 22nd July 1911 issue of The Moving Picture World reporting on Brighton's death and documenting his career (found on Internet Archive, p.g. 112). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 13th July 1911 issue of Birmingham Daily Gazette reporting on Brighton's passing and noting he had tested the pond's depth beforehand (found on The British Newspaper Archive, p.g. 5). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 12th July 1911 issue of The Meriden Daily Journal reporting on Brighton's drowning and his career (found on Google Newspapers, p.g. 6). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 17th July 1911 issue of The New York Times reporting on Belmar publicly screening the footage of Brighton's drowning and the rescue attempts (p.g. 18). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 13th July 1911 issue of The Glasgow Herald reporting on the drowning and how nobody intervened until it was too late (found on Google Newspapers, p.g. 7). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Digital Humanities Studio stating Henry Belmar's wife's name was Laurel Love and summarising the aborted Abraham Lincoln production. Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 13th July 1911 issue of Globe reporting on the drowning and the claim that the villain threw the protagonist's wife into the water (found on The British Newspaper Archive, p.g. 7). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ BBC detailing the effects of being stuck in wet quicksand. Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 22nd August 1911 issue of Zeehan and Dundas Herald reporting on the tragedy (found on Trove, p.g. 4). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 29th July 1911 issue of The Moving Picture World lambasting Belmar and the Morning Telegraph for screening and marketing footage of Brighton's drowning (found on Internet Archive, p.g. 202). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 November 1911 issue of The Motion Picture Story Magazine responding to a query regarding the availability of Brighton's death footage (found on Internet Archive, p.g. 140). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Small Town Noir summarising the final years of Belmar's life. Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 12th June 1918 issue of The Norwalk Hour reporting on Belmar's plans to film a biography on Abraham Lincoln (found on Google Newspapers, p.g. 29). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 25th October 1913 issue of Picturegoer listing early accidents in filmmaking, including Brighton's drowning (found on The British Newspaper Archive, p.g. 10). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 17th May 1913 issue of The Advertiser (Adelaide) listing some accidents during early filming, including Brighton's death (found on Trove, p.g. 7). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ 28th December 1912 issue of The Mansfield Shield documenting cases of accidents in early filmmaking, including Brighton's passing (found on Google Newspapers, p.g. 3). Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ Film Foundation claiming that roughly 90% of pre-1929 films are forever lost. Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ Deutsche Kinemathek stating roughly 80-90% of silent films are permanently missing. Retrieved 18th Oct '24

- ↑ Ben Beck's Website summarising early recorded death footage, including that of Franz Karl Reichelt and Emily Davison. Retrieved 18th Oct '24