Jeffries-Sharkey Contest (partially found footage of boxing match; 1899)

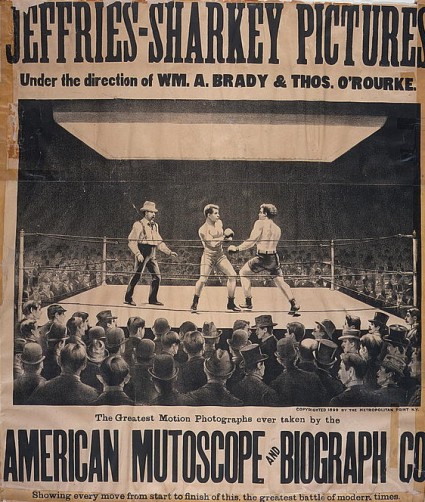

Promotion of American Mutoscope and Biograph Company's Jeffries-Sharkey Contest.

Status: Jeffries-Sharkey Contest - Lost / The Battle of Jeffries and Sharkey for Championship of the World - Found / Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight - Lost

On 3rd November 1899, James J. Jeffries defended his World Heavyweight Championship against Tom Sharkey. A rematch of their 6th May 1898 encounter, it took place at the Coney Island Athletic Club in New York, and saw Jeffries again claim victory via decision, following a brutal 25-round affair. This boxing match is also historic for inspiring one of the longest film recordings of its era, with seven and two-third miles of footage being captured under artificial light. Whereas the official American Mutoscope and Biograph Company version titled Jeffries-Sharkey Contest remains missing, an unauthorised Vitagraph Company recording, which attracted extensive controversy, has survived. Additionally, a supposed "reproduction" of the fight has also been lost to time.

Background

On 9th June 1899, James J. Jeffries had won the World Heavyweight Championship by securing an 11th round KO victory over Bob Fitzsimmons.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Prior to his second match with Tom Sharkey, Jeffries had yet to defend his title, having embarked on recreating some of his famous fights to be shown on film, and competing in exhibition bouts in Europe.[3][2] His original bout with Sharkey occurred at the Mechanic's Pavilion in San Francisco on 6th May 1898, where he won by decision after 20 rounds.[7][1] This match was actually used to determine the next contender for the world title; the Los Angeles resident successfully defended said claim against Bob Armstrong on 5th August 1898, again by decision.[1] Meanwhile, Sharkey had previously claimed the World Heavyweight Championship in pretence following a controversial disqualification victory over Fitzsimmons on 2nd December 1896, in a bout involving Wyatt Earp as the referee.[8][7] While his original loss to Jeffries was a setback, wins against Gus Ruhlin, James J. Corbett, Charles 'Kid' McCoy, and Jack McCormick helped to legitimise the Irishman's ambitions for a subsequent rematch, this time with the world title on the line.[7] Heading into the bout, Jeffries had a height and weight advantage over his opponent, standing at 6' 2" compared to 5' 8" and weighing around 210 lbs compared to Sharkey's 185 lbs.[9][1][7]

Meanwhile, Jeffries' manager William Brady brokered an exclusive filming rights deal with the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, with sponsorship provided by Sharkey's manager Tom O'Rourke.[10][11][6][4][9] Boxing films had become a highly lucrative business thanks to the success of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight in 1897, said to be the first-ever feature film and among the biggest box office attractions of its era.[12][4][9] Despite prizefighting in America technically being illegal until 1920, it did not stop companies like American Mutoscope from seeing the contests as a licence to print money.[13][5][4][9] The company prioritised quality, recording scenes with a 70mm Biograph Camera.[14] This camera garnered a reputation for capturing smooth and substantial quality scenes that lacked unintentional flicker effects found in most 20th-century films.[14][9][10]

Hence, American Mutoscope spared no expense during production for its latest film, titled Jeffries-Sharkey Contest.[15][10][9][4][11] It brought four cameras in for the event, managed by Frederick S. Armitage, Georg William Bitzer, Arthur Marvin, and eight other operators.[4][15][11] Placed on a platform, three cameras would be in constant rotation, with one recording footage, one fully loaded to take over from the active camera, and the third in the process of being reloaded with film.[10][4][9][6] The fourth was a backup should one of the others fail.[10][9] The company, anticipating the fight could last all 25 rounds, also transported an extensive amount of film within 40 film boxes that could store 1,365 feet each.[15][6][10][9][11] In total, around 40,500 feet or seven and two-third miles of film was reportedly captured, with 320 feet required for each minute of footage recorded at 30 frames per second.[15][10]

Eleven electricians were hired to install 400 arc lamps around the arena, with each containing reflectors.[15][11][4][10][9] This reportedly made the bout the first to be filmed under artificial light.[16][15] Apparently, this was enough to provide sufficient light to a city with a population of 100,000.[15] So that the arena was adequately lit for quality filming, the decision was made to avoid opening the roof.[9][11] This attracted controversy, for the heat from the arena lights caused indoor temperatures to reach 115 degrees, adding another gruelling aspect to an already brutal fight.[10][4][9][11] While Sharkey claimed he was unaware of the lamps and managed to withstand the intense heat following the first round, he and Jeffries requested that such a situation was never repeated in their future fights.[15][10]

American Mutoscope successfully captured 24 of the 25 rounds.[10][9][11] There were technical challenges to overcome, mainly to ensure the processes of perforating and buckling of the film occurred while avoiding excess light from ruining the picture.[10] This was achieved through an illuminated red-glass peephole that cameramen would routinely inspect throughout the fight.[10] When it came time to capture the final round, a blown fuse thwarted any further recording, though The History of the Discovery of Cinematography and some news reports claim American Mutoscope merely ran out of film.[10][9][11] This, naturally, was a major issue as film viewers would certainly be expecting to see the fight's conclusion.[10][9] Thus, American Mutoscope persuaded a reluctant Jeffries and Sharkey to re-enact the final round under the same conditions a week following their encounter.[10][9] It appeared worth it, as American Mutoscope, Brady, and the boxers were all set to highly profit from the film, which could only be viewed via a Mutoscope.[9][6][11] However, it was soon revealed that another filmmaker was in attendance that night, and was not just there to witness the spectacle unfold.[6][11][10][9]

The Fight

The bout itself was set for 27th October 1899, but was delayed until 3rd November.[17][1][7] This was the result of Jeffries injuring his left arm prior to 18th October.[17] Although O'Rourke was sceptical regarding the injury's severity, he nevertheless agreed to have the fight delayed by a week.[17] This actually marked the bout's second delay; it was reportedly initially set to commence on 23rd October though it was later determined that 27th October was a more ideal fight date.[17]

Around 19,000 spectators packed the Coney Island Athletic Club in New York, among them several top boxers of the era.[5][16] "Boilermaker" Jim Jeffries rubbished concerns he was not 100% with a powerful 210 lb build.[16][5] Indeed, Jeffries was noted for his highly disciplined and scientific training routine, maintaining a ruthless diet and exploring new techniques for delivering powerful hits.[16] However, "Sailor" Tom Sharkey, who entered the ring donned in green trunks, was also in peak condition and was certainly no pushover despite his weight and height disadvantages.[5][16] The New York Times summarised the fight as a "battle of giants", with the contestants in the ring by 19:15 pm.[5] The 25-round bout was contested under the Marquis of Queensberry rules; both boxers competed in three-minute rounds wearing padded gloves, with a minute rest per round.[18][5] KOs could occur if a boxer could not get up unsupported after ten seconds.[18]

Both immediately went on the offensive, but it was the defending champion who gained the initial advantage.[19][16][5] The Summit County Journal believed Jeffries controlled the first two rounds, culminating with him achieving a knockdown via a left hook to Sharkey's jaw.[19][16] However, Sharkey got up and instantly fought back, landing hooks and shots to his foe's ribs and generally gaining the upper hand from the third round onwards.[19][16] Jeffries recalled Sharkey was a unique opponent for him, as his small stature and agility made it difficult for the champion to land accurate blows.[16] Even when Jeffries did secure hits, even knocking Sharkey towards a corner, the Irishman simply charged right back.[16][19] Unlike most boxers Jeffries fought, Sharkey went backwards when hit instead of falling forward, demonstrating crucial durability.[16]

As the fight progressed, Sharkey inflicted key cuts and splits to Jeffries' ear, eye, and nose.[19][16] However, his biggest offence was inflicted on the defending champion's neck, landing powerful left hooks on it with such consistency that The New York Times deemed "the flesh there was as raw as a piece of beef."[5] Despite this, no knockdown emerged, with Jeffries countering with some brutal body blows that affected Sharkey's ribs and stomach.[16][19] Both were gunning for a KO victory, subsequently delivering a slugging contest that also contained numerous instances of holding, forcing referee George Siler to routinely intervene.[19][16][5] Particularly, Jeffries used his weight advantage to try and control his opponent's movements, indicating a win-at-all-costs mentality from both.[19] Worse still, the trapped heat produced by the arc lamps raised the arena temperature to 115 degrees.[11][4][19][9][10] Both boxers were weakened by dehydration, and the heat's intensity actually singed their hair.[9] Without even intending to, American Mutoscope was somewhat artificially changing the match's direction and outcome.[9]

Still, Sharkey was prevailing up until the 20th round.[16][5][19] At that point, a right body blow was enough to break two of the Irishman's ribs.[16][19] While he was able to continue, his powerful offence was greatly diminished.[16] In contrast, Jeffries' stamina remained strong, enabling him to launch a comeback two rounds later, delivering two hooks onto Sharkey's jaw that stunned the challenger.[19][16][5] Sharkey, in spite of clear facial damage to his eyes and ears, continued onwards, but he was unable to truly contend with Jeffries' relentless offence, which included two powerful uppercuts.[19][16][5] In the final round, after shaking hands beforehand, an exhausted Sharkey ended up knocking off Jeffries' left glove.[19][16][5] Amidst Siler desperately trying to correctly readjust the champion's glove, Sharkey charged one more time, though his attacks were blocked by the champion.[5][19][16] In contrast, Jeffries landed another left hook to the jaw as the match concluded with the referee trying to separate the contestants.[16][19][5] The Summit County Journal felt Jeffries only won the first two rounds and the final three.[19] However, it was still enough for him to achieve victory by decision.[19][16][5][9][1][7]

Post-fight, Sharkey expressed that he was "robbed" of victory, believing he should have won on points after controlling most rounds and even accused Siler of having a vendetta against him.[19] He also revealed he fought the final five rounds with broken ribs, insisting he could beat Jeffries in a third clash.[19] Meanwhile, Jeffries criticised Sharkey for underhanded tactics, accusing the Irishman of utilising headbutts and frequent elbow blows, while also claiming he could have achieved a seventh round knockout were it not for his injured left arm playing up.[19] He concluded that the electric lights' heat greatly reduced his strength, and insisted on no more filmed fights under its current layout.[19][10] Ultimately, despite the second encounter lasting for an hour and 40 minutes and being a close affair, a third match between the pair never materialised.[16][5]

Sharkey fought 13 more professional matches, his last being a newspaper decision loss to Jack Munroe on 27th February 1904.[7] While he never became World Heavyweight Champion, Sharkey was declared among the top 100 boxers according to Ring Magazine, having also achieved 39 KOs in 54 matches.[20] Meanwhile, Jeffries retired as champion, ironically beating Munroe by TKO on 26th August 1904 in his final defence.[1] However, he was coaxed out of retirement for an ill-fated match against World Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson on 4th July 1910, becoming the "Great White Hope" where he proceeded to lose via TKO.[1][2][3][5] Despite their brutal encounters, Jeffries and Sharkey maintained a solid friendship, with the pair also resolving their ever-growing financial troubles as the years went by, including partaking in a 1926 vaudeville tour together.[16] Jeffries retrospectively declared that Sharkey was "the toughest bird I ever fought".[16]

Filming Controversy

After recording the fight and the round 25 re-enactment, American Mutoscope planned to sell Jeffries-Sharkey Contest in 200 feet rounds to various exhibitors across the United States.[21][22][4] According to the AMB Catalogue 1902, the introduction and post-fight sequences were 600 and 25 feet respectively.[21][22] Boasting that it was "the greatest and longest moving picture film ever made", American Mutoscope's production was reported on by the October 1899 issue of The Phonoscope, who praised the technological advancements the work made, especially how the effectiveness of the artificial light meant motion photography no longer required sunlight.[15]

The company had attempted to protect their investment by having Pinkerton security guards detect any piracy attempts within the arena.[21][22][9][6][10] However, Albert Smith, along with another Vitagraph Company filmmaker, smuggled a 35 mm camera into the vicinity and began capturing footage behind the American Mutoscope cameras.[11][6][9][10] Some accounts indicate he obscured his camera via a jacket, a cigar box, or even a pile of umbrellas.[11][10] However, The History of the Discovery of Cinematography disputes this, as it would have been impractical to hide a massive 20th-century camera.[10] Smith recorded around five minutes of the fight, before retreating in the wake of pursuing Pinkerton.[11][9][10] He successfully managed to reach the Vitagraph production plant and had the film developed there.[6][11][9][10]

The following morning, Smith, to his horror, discovered that the sole recording had been stolen.[6][11][10] An individual smuggled the film to Edison Studios, who eagerly began production of 35mm copies under the title of The Battle of Jeffries and Sharkey for Championship of the World.[23][9][6][11][10] There was little Vitagraph could actually do to resolve the crisis; aside from the recording being unauthorised to begin with, Edison had also filed an injunction against the company for a separate incident.[6] Thus, a deal was made where only a single print of The Battle of Jeffries and Sharkey for Championship of the World was sold under the Vitagraph name.[6] The rest would directly profit Edison, thus undermining both Vitagraph and American Mutoscope.[6][9] Allegedly, a plan was in place to artificially increase the film's length by looping it, in turn tricking viewers into believing they were witnessing multiple "rounds" of the fight.[9]

Muddying the waters further was Siegmund Lubin's film released under the Lubin Manufacturing Company label.[24][13][6][9][12] Lubin identified a deviant gap within the boxing film market; by harnessing detailed newspaper reports of boxing matches, he could simply "reproduce" them.[6][13][12][9] For example, hot on the heels of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight's commercial success, Lubin filmed and released Reproduction of Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight that same year.[12][6][13] This "reproduction" did not actually feature Corbett or Fitzsimmons; rather, Lubin employed two railroad freight handlers to act as the boxers and "re-enact" their famous bout.[24][6] The business plan behind these "reproduction" films was to trick gullible viewers into watching what they thought was the real clash.[6][24] Regardless of how angered the paying audience was, these films, which sometimes even featured the real boxers, were successful enough to take a chunk of profit from their legitimate counterparts.[6][24][9][12][13] Seeing profitability behind the Jeffries-Sharkey fight, Lubin released Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight, with this film certainly not featuring either boxer in action.[25][6][9][12][13]

One may question how Vitagraph, Edison, and Lubin were even able to market their productions, especially since American Mutoscope had supposedly gained exclusive filming rights for the fight.[6][9][11] Back then, motion pictures were not actually fully copyright protected until The Townsend Amendment of 1912 ensured films were added to the list of protected works.[26][11][13] The only means of guaranteeing some protection before 1912 was to take some representative photographs of the film, send them to the Copyright Office, and gain copyright protection that photos had enjoyed since 1865.[11][26] However, Edison promptly filed copyright protection on 4th November 1899 via James H. White.[6][11] Lubin also beat American Mutoscope in making its work copyrighted and subsequently began legal action against the latter for supposed "copyright infringement".[9][6] Lubin's work was not a pirate, as it was an original production.[6] Thus, it technically was a copyrighted work, something that Lubin proudly boasted in a New York Clipper advertisement offering $10,000 to anyone who could successfully dispute its copyright status.[27][6]

Ultimately, the failure to prevent Vitagraph's recording and slow stance in filing copyright protection cost American Mutoscope significant revenue.[6][9] While it was able to release Jeffries-Sharkey Contest, it was forced to battle both the Vitagraph/Edison pirate and the Lubin knock-off.[6][11][9] Counter-lawsuits were filed, but because legal results would take years to unfold, the real contest commenced through promotions belittling the competition and encouraging viewers to see the legitimate, high-quality work.[6] Thus, American Mutoscope, Brady, Jeffries, and Sharkey did not receive the profits they were anticipating.[6][9] Nevertheless, Jeffries-Sharkey Contest, despite losing a hefty chuck of potential revenue, still managed to make around $200,000 at the box office.[9] The rise of nickelodeons from 1904 also saw a surprising upsurge in the film's popularity too.[4] Meanwhile, Lubin continued with his reproductions, with American Mutoscope also engaging in the same practice with the 1903 film Reproduction of Corbett-McGovern Fight.[12][13][6] However, after seeing his own legitimate works suffer in profitability, successful legal action by Thomas Edison himself stopped the questionable practice altogether by the early-1900s.[13]

Availability

Some footage of the second Jeffries-Sharkey fight survives.[9][11][10] But in a rather frustrating twist, only Vitagraph/Edison's The Battle of Jeffries and Sharkey for Championship of the World has been recovered intact, lasting for around five minutes.[9][10][11][23] It is unclear how Jeffries-Sharkey Contest became lost, but chances are it was made further prone to becoming missing because most exhibitions were unlikely to have purchased the entire seven-mile+ film, instead settling on a few 200 feet rounds.[4][21][22] The 35 mm Vitagraph recording was assessed by various sources as vastly inferior because of the flickering effect, short length, and how some action is obscured by the audience, thus making the higher-quality American Mutoscope production's lost status especially unfortunate.[9][10][11]

Only a few still photographs of the film are publicly available, as these were used as part of American Mutoscope's copyright registration.[11][9] A potential opportunity to preserve the production was lost during copyright filing; some film companies opted to provide an entire print to the Copyright Office and claim all the frames as copyrighted photos.[11] Alas, American Mutoscope decided to only provide some representative shots of its films.[11] Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight, which was measured at 3,750 feet with each round supposedly lasting 150 feet, is also presumed lost.[25] About 75% of the United States' silent films have been declared permanently lost, making the chances of Jeffries-Sharkey Contest or Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight resurfacing intensely slim.[28]

Gallery

Videos

See Also

- Barbara Buttrick vs Gloria Adams (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1959)

- Bill Lewis vs Freddie Baxter and Archie Sexton vs Laurie Raiteri (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1933)

- Cassius Clay vs Tunney Hunsaker (partially found footage of boxing match; 1960)

- Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- England vs Ireland (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1937)

- Evander Holyfield Championship Boxing (lost build of cancelled Game.com boxing game; 1999)

- Exhibition Boxing Bouts (lost early television coverage of boxing matches; 1931-1932)

- The Fighting Marine (lost Gene Tunney drama film serial; 1926)

- Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1926)

- Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey (partially lost radio coverage of "The Long Count Fight"; 1927)

- Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)

- Heavyweight Champ (lost SEGA arcade boxing game; 1976)

- Jack Dempsey vs Billy Miske (lost radio report of boxing match; 1920)

- Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Jo-Ann Hagen vs Barbara Buttrick (lost radio and television coverage of boxing match; 1954)

- Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Len Harvey vs Jock McAvoy (partially found footage of boxing match; 1938)

- Leonard-Cushing Fight (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- Marcel Cerdan vs Lavern Roach (lost footage of boxing match; 1948)

- Rocky (lost deleted scenes of boxing drama film; 1976)

- Super Punch-Out!! (lost beta builds of SNES boxing puzzle game; 1994)

- Title Defense (lost build of cancelled boxing simulation game; 2000-2001)

- Uncle Slam and Uncle Slam Vice Squad (lost iOS presidential boxing games; 2011)

External Links

- IMDB page for Jeffries-Sharkey Contest.

- IMDB page for Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 BoxRec detailing Jeffries' fight record. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 International Boxing Hall of Fame page on Jeffries. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 PSA summarising the career of Jeffries. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Inspired by True Events summarising The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight and Jeffries-Sharkey Contest. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 3rd November 1899 issue of The New York Times reporting on the fight. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 American Cinema 1890-1909 detailing how Vitagraph, Edison, and Lubin all managed to successfully produce unauthorised films of the fight. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 BoxRec detailing Sharkey's fight record. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ When Boxing Was, Like, Ridiculously Racist summarising Sharkey's controversial win over Fitzsimmons and his claim to the World title. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 9.22 9.23 9.24 9.25 9.26 9.27 9.28 9.29 9.30 9.31 9.32 9.33 9.34 9.35 9.36 9.37 9.38 9.39 9.40 9.41 9.42 The Bioscope providing extensive detail of the fight, the filming and the controversies surrounding it. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 10.19 10.20 10.21 10.22 10.23 10.24 10.25 10.26 10.27 10.28 10.29 The History of the Discovery of Cinematography detailing the production of Jeffries-Sharkey Contest. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 11.24 11.25 11.26 11.27 11.28 Copyright Lore detailing the controversies surrounding pirate recordings of the bout, and what remains of the American Mutoscope film. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Dirty Words and Filthy Pictures summarising the lucrative nature of early boxing films, including ones made by Lubin and American Mutoscope. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 Film Censorship in America detailing the controversies surrounding the Lubin reproductions, and how they were eventually stopped. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Archived Society of Camera Operators providing a 1939 interview regarding the Biograph Camera. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 October 1899 issue of The Phonoscope reporting on the American Mutoscope film and its technical achievements. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 16.17 16.18 16.19 16.20 16.21 16.22 16.23 16.24 16.25 Boxing Scene documenting the bout, and the friendship between the two boxers. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Cyber Boxing Zone providing two newspaper clippings reporting on the fight's delay due to Jeffries' left arm injury. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Britannica documenting the Queensberry rules. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 11th November 1899 issue of The Summit County Journal reporting on the fight and the boxers' post-match comments. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ Ring Magazine summarising the career of Sharkey (article found on archived TIME). Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 American Film Institute Catalog listing of Jeffries-Sharkey Contest. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 AMB Catalogue 1902 promoting the film. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 American Film Institute Catalog listing of The Battle of Jeffries and Sharkey for Championship of the World. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 First Cinemakers summarising Lubin's practices, including for his infamous Reproduction of Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 American Film Institute Catalog listing of Reproduction of the Jeffries and Sharkey Fight. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Copyright Lore detailing the Townsend Amendment of 1912. Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ 25th November 1899 issue of New York Clipper advertising Reproduction of the Jeffries-Sharkey Fight and its $10,000 offer (article found in The Emergence of Cinema). Retrieved 11th Aug '23

- ↑ The Atlantic reporting on how most American silent films have been declared permanently lost. Retrieved 11th Aug '23