1922 Indianapolis 500 (lost radio coverage of AAA race; 1922)

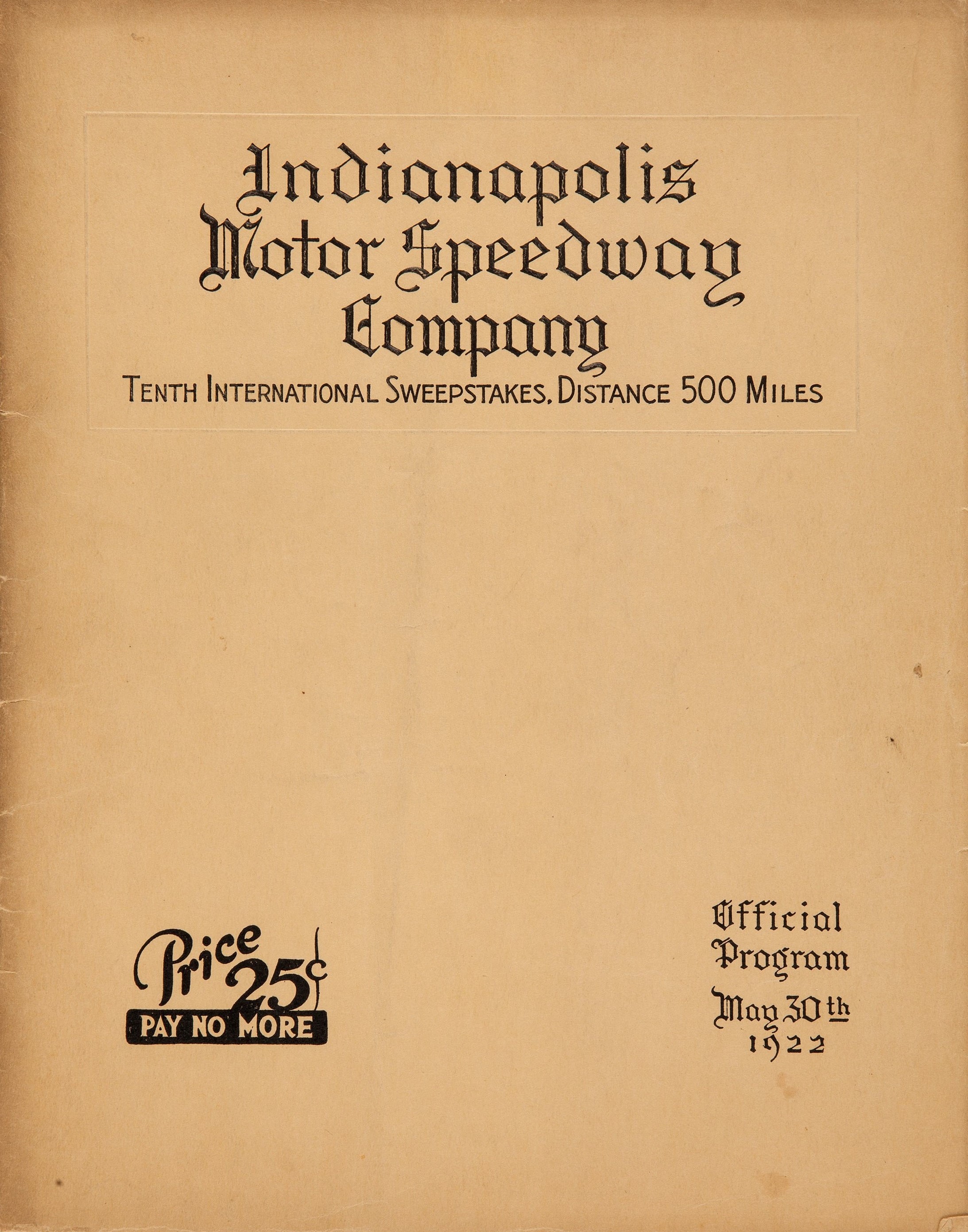

The 1922 Indianapolis 500 (then known as the 10th 500-Mile International Sweepstakes Race) was an Indianapolis Motor Speedway race sanctioned by the American Automobile Association (AAA) and held on 30th May 1922. It witnessed Jimmy Murphy win the event in a Duesenberg-Miller, making history as the first to claim glory after winning the pole position. From a media standpoint, the 1922 edition was the first to receive radio coverage.

Background

First held in 1911,[1] the Indianapolis 500 is often regarded as the crown jewel of IndyCar racing, primarily thanks to its longevity and prestige.[2] Billed as lasting for 500 miles or 200 laps of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway,[3][4][2] the 1922 edition was held before fellow Triple Crown of Motorsport races, the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the Monaco Grand Prix, even existed.[5] AAA sanctioned the race and would continue to do so until it withdrew after 1955 and was replaced by the United States Automobile Club (USAC).[6][2]According to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website, a prize pot of $58,075 was on offer, with $20,000 ($373,271 when adjusted for 2024 inflation[7]) automatically going to the race winner.[8][9] However, newspapers like The New York Times and The Pittsburgh Press claimed that the full total was between $85,000 to $100,000.[10][11]

Of the entrants for the 1922 edition, four were previous Indianapolis 500 winners.[3][1] These included Jules Goux (1913), Ralph DePalma (1915), Howdy Wilcox (1919), and defending champion Tommy Milton, who was entering with a brand-new Milton-Miller.[11][1][3] But they were all beaten to the pole position by Jimmy Murphy,[3] who was competing in his third Indianapolis 500.[12] He had previously finished fourth in the 1920 edition and crashed out the following year.[12] But Murphy certainly had momentum on his side for 1922 as he dominated the overall AAA National Championship Trail, having finished no lower than third in the first nine races.[13][14] He entered the event in his own Duesenberg-Miller,[15] which he coined as the "Murphy Special".[14][3] It was notably the same chassis he utilised to win the 1921 French Grand Prix despite having to nurse two broken ribs in a prior practice accident.[16][11][9] With this, he became the first American to win a European race.[14] The key difference was that he opted to replace the Duesenberg engine with a straight-eight Miller one.[17] He was notably the last to submit an application for the 1922 Indianapolis 500.[11] Over four qualifying laps, Murphy won the pole position with an average speed of 100.5 mph.[18][8][9] Not only was he the sole driver that year to break the 100 mph barrier,[8] but he also broke Wilcox's speed record of 100.010 mph set in 1919.[1] Until the 1923 edition, the AAA stipulated that all entrants must bring a riding mechanic with them.[17] In Murphy's case, he selected Ernie Olsen for the race.[3]

Indy rookie Harry Hartz and the veteran DePalma lined up second and third respectively, both having entered with a Duesenberg engine and chassis combination.[19][3] At the time, DePalma had set the fastest average speed of 89.84 mph for the 1915 race.[11][1] Further down the field were entrants from England, France and Italy.[10] Among them was Douglas Hawkes, who qualified 19th out of 27 entrants and became the first (and as of 2024, only) driver to enter with a Bentley.[20][15][11][3] Whereas DePalma qualified strongly, his fellow former race winners struggled, with Goux lining up 22nd in a Ballot, Milton 24th in a Milton-Miller, and Wilcox 26th driving for Peugeot.[3] They were among the final ten to have qualified for the race, with Milton, in particular, leaving it late to attempt a fast time.[19] In 23rd was Eddie Hearne in a Ballot.[3] In direct contrast to Murphy, Hearne became the first to officially enter the race, where he was singled out by The Pittsburgh Press as one to watch.[11] This time, Hearne and Hartz would be in direct competition, the latter having served the former as his riding mechanic for the previous three 500s.[15]

Among entrants who failed to qualify included D'Wehr drivers Frank Davidson and Rudolph Wehr; William Gardner in a Bentz; Tommy Mulligan, who had crashed out in practice driving Jack Curtner's Ford T-Fronty-Ford; while Wallace Reid (Duesenberg) and Charles Shambaugh (Shambaugh) both withdrew.[3][10] In Curtner's case, the car was repaired in time for the race but had yet to demonstrate that it could reach a mandatory average speed of at least 80 mph in qualifying.[10][19][15] Because of this, the AAA did allow Curtner to compete as the Ford had been quick in other events, but it was ineligible for prize money.[10][15] Interestingly enough, Mae Harvey became the first woman to attempt to enter a car for the event.[18] However, the intended driver for her Frontenac opted to enter with his own vehicle, leaving Harvey without a representative.[18]

The 1922 Indianapolis 500 achieved a then-record attendance of around 135,000, up by 5,000 from the previous year's event.[9][10] According to the 31st May 1922 issue of The Indianapolis Star, the race likely generated over $500,000 in revenue, with $270,000 received at the gate.[9] One little-known fact is that Arthur Pinder and his wife from Terre Haute had consistently been the first to reach the Speedway's driveway, with this being the couple's fifth successful outing in a row.[9] Then-Chairman of the Contest Board of the AAA, Richard Kennerdell, was selected to officiate the race.[21] Barney Oldfield was the pace car driver while Eddie Rickenbacker gave the instruction for the drivers to start their engines.[22][18]

Radio Coverage

Additionally, this was the inaugural Indianapolis 500 to receive radio coverage, courtesy of WLK and WOH.[23][24][25] Back then, live broadcasts were possible, as KDKA had aired the Johnny Ray-Johnny Dundee boxing match on 11th April 1921.[26] However, considering the Indianapolis 500 typically lasted over five hours,[3] a full race broadcast was a tad too early during radio's formation years.[24] Nevertheless, WOH opted to broadcast key race highlights through its Star-Hatfield broadcasting studio.[9] Officially opened on 25th March 1922,[27] the Hatfield Electric Company-owned WOH became Indianapolis' second radio station.[24] Following a successful test that indicated the commentary and racing action was clearly audible, WOH incorporated a wire onto the judges' stand, and a six-foot megaphone at the studio itself. According to the 30th May 1922 issue of The Indianapolis Star, WOH's program promised to cover the list of entrants, line-up and race start. From 10:10-10:45 am, 10:45-10:55 am, and 13:15-13:30 pm, WOH aimed to provide coverage of key race events, as well as official bulletins surrounding race progress. At 16:00 pm, WOH would conclude its coverage by revealing the race results.[23]

The Indianapolis Star also confirmed WLK provided race coverage.[23] The inaugural Indianapolis radio station, it was forged as 9ZJ by Francis F. Hamilton before being designated as WLK upon obtaining a commercial licence.[28][24] During gaps in WOH's coverage, WLK provided occasional race news updates from its News-Ayres-Hamilton studios.[23] While The Indianapolis Star claimed that the broadcasts would be received across the United States,[23] Kevin Triplett's Racing History noted this was probably untrue since neither station boasted powerful transmitters.[24] Nevertheless, the 31st May 1922 issue of Warsaw Daily Times confirmed the broadcasts were certainly heard throughout Indiana, allowing the print media to listen in and gain a head start in writing their race reports.[29]

The coverage kickstarted over a century of Indianapolis 500 radio coverage.[24][25][9] Additionally, Auto Racing in the Shadow of the Great War declared it as the first motor racing event to receive radio reports.[18] Seven years later, the event was fully covered live on radio courtesy of WKBF and WFBM.[30] In 1952, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Radio Network's formation centralised future broadcasts.[25] On a separate note, it is known that Fronty-Ford drivers Curtner and Ralph Mulford,[3] as well as a Monroe racer, were able to achieve two-way radio communication with their pit crews.[31] This represented another technological milestone in racing and subsequently depreciated blackboard race signals.[31]

The Race

With the starting order decided, the 1922 Indianapolis 500 commenced on 30th May.[3] Murphy made a strong start, having led the first 73 laps of the race.[9][3] He was then overtaken by the Frontenac driven by Leon Duray, who himself was passed by Hartz two laps later.[9][3] Further down the field, Wilcox, Goux and Milton were already out following mechanical failures, reportedly involving a valve spring, a broken axle and a leaking gas line respectively.[22][3] After completing 25 laps, Jules Ellingboe and his riding mechanic Thane Houser were fortunate to escape injury after their Duesenberg's right rear wheel clipped the south turn, causing it to be sent into a concrete retaining wall.[22][3] Another incident witnessed Wilbur D'Alene and riding mechanic Worth Schloman sustain minor burns when their Frontenac suffered a fiery exit.[22][3]

Hartz was overtaken by Frontenac driver Peter PePaolo on lap 83 but regained it three laps later.[3][9] PePaolo then crashed out after 110 laps when his car hit the outside retaining wall.[22][3] Despite the initial collision and the fact it redirected their Frontenac over one hundred feet across the track, PePaolo and riding mechanic Jimmy Brett escaped unharmed.[22] Indeed, despite Indianapolis Motor Speedway's reputation for serious accidents,[32] no injuries were reported during the 1922 edition.[9] With PePaolo out, the event became a two-horse race between Hartz and Murphy.[3] Hartz remained in front until lap 122nd when Murphy repassed him and never looked back.[9][3] During the event, Murphy pitted three times, with news reports praising his quick pit crew for taking just 28 seconds to replace a front right tyre.[22][31] From there, Murphy continually extended his lead and his average speed.[22] According to The New York Times, Murphy responded to erroneous timekeeping that saw Hartz briefly declared the race leader after 200 miles, thus helping him "reassume" the first position.[22][31]

Thus, Murphy took the chequered flag waved by Rickenbacher to claim victory and a guaranteed $20,000 in prize money.[8][9][22] According to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website, Murphy's full winnings totalled $28,075 when accounting for other prizes like number of laps won.[8] This in itself attracted minor controversy; while The New York Times and The Quebec Daily Telegraph claimed Murphy made history by leading every lap,[22][31] The Indianapolis Star reported that the race judges later deduced Hartz, PePaolo and Duray had indeed led at points of the event.[9] Websites that provide race results - including the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website - note Murphy actually led 156 of the 200 laps.[8][3] Murphy also earned the Prest-O-Lite Trophy, L. Strauss Cup, the Wheeler Schebler Trophy and the Rayfield Trophy for leading the event at key intervals.[33][9] In second was Hartz, who was three minutes down from Murphy.[3][9][22] Among his prizes totalling $10,000 included a $100 radio.[9][8] Hearne climbed from 23rd to obtain the final podium position;[3][22] according to The Indianapolis Star, his Ballot was the only competitive car entered outside of America.[9] DePalma, a race favourite,[22][31] took fourth with fellow Duesenberg driver Ora Haibe in fifth.[3] It was a strong event for Duesenberg in general, as eight of its cars and/or engines were in the top ten.[15][3] In 13th and last was Hawkes; though his four-cylinder Bentley proved uncompetitive, it nevertheless gained appreciation from the fans for its endurance.[22][9]

Though Murphy may not have led all 200 laps, he still made history by becoming the first polesitter to win the Indianapolis 500.[15][1] His average speed of 94.484 mph and time of 5:17:30.79 smashed DePalma's 1915 record of 89.840 mph (5:33:55.51).[9][3][1] In fact, the top five all achieved average speeds over 90 mph.[9][3] This also marked the last Indianapolis 500 to feature engines boasting a maximum 183-inch piston displacement, with the 1923 regulations mandating a limit of only 122.[17][15] Following this, Miller engines and chassis dominated the event up until the late 1930s.[15][1] Murphy continued to dominate the 1922 AAA National Championship Trail, claiming the title with 3,420 points, 1,510 more than runners-up Milton.[13][14] He entered the following two Indianapolis 500s, finishing third in both and winning the 1924 pole position.[12] Murphy passed away on 15th September 1924 aged 30 following a fatal accident at the 150 dirt race at the New York State Fairgrounds.[34][14] He earned enough points to be posthumously declared as the 1924 AAA National Champion.[35][34]

Availability

The 1922 Indianapolis 500's radio coverage was transmitted during a period where recordings were seldom made.[36][37] No regular radio broadcasts are known to have survived before President Woodrow Wilson's Armistice Day speech in 1923.[37][36] Outside sports broadcasts were typically left unrecorded because of the impracticality of transporting primitive recording devices to and from radio studios.[38] Thus, the entirety of WLK and WOH's coverage is believed to be lost. The oldest publicly available radio coverage of the Indianapolis 500 appears to originate from 1939,[39][40] although some online discourse indicates parts of the 1928 broadcasts survive as well.[41] Nevertheless, various race photographs of the 1922 event can be viewed via the Indianapolis Motor Speedway website.[42]

Gallery

Videos

See Also

- 1962-1963 USAC Championship Car Seasons (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1962-1963)

- 1964-1965 USAC Championship Car Seasons (lost footage of IndyCar races; 1964-1965)

- 1966-1968 USAC Championship Car Seasons (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1966-1968)

- 1969 USAC Championship Car Season (lost footage of IndyCar races; 1969)

- 1970 USAC Championship Car Season (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1970)

- 1971 USAC Championship Car Season (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1971)

- 1972 USAC Championship Car Season (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1972)

- 1973-1975 USAC Championship Car Seasons (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1973-1975)

- 1976 USAC Championship Car Season (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1976)

- 1977 USAC Championship Car Season (lost footage of IndyCar races; 1977)

- 1978 USAC Championship Car Season (partially found footage of IndyCar races; 1978)

- 1980-present IndyCar races (partially found footage of USAC, CART, and IRL races; 1980-present)

- Indianapolis 500 MCA closed-circuit broadcasts (partially lost racing footage; 1964-1970)

- Indianapolis 500 WFBM-TV Broadcasts (lost racing footage; 1949-1950)

- Indycar (Unreleased Motorsport Games Indycar Game, 2023)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Indianapolis Motor Speedway detailing the winners of the Indianapolis 500. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Planet F1 summarising the history and prestige of the Indianapolis 500. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 ChampCar Stats detailing the qualifying and race results of the event. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Racing Circuits detailing the history of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Racing News 365 summarising the Triple Crown of Motorsport and noting the Indianapolis 500 was the only one of the three to exist by 1922. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ ESPN noting the 1956 Indianapolis 500 was the first to not be sanctioned by the AAA. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ in2013dollars noting $20,000 in 1922 is equal to $373,271 when adjusted for 2024 inflation. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Indianapolis Motor Speedway detailing the qualifying and race results and noting the prize winnings. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 31st May 1922 issue of The Indianapolis Star reporting on the race (found on Newspapers.com, clipped by doctorindy500, p.g. 16. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 29th May 1922 issue of The New York Times previewing the race (p.g. 8). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 21st May 1922 issue of The Pittsburgh Press previewing the drivers entering the event (p.g. 75). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Indianapolis Motor Speedway detailing Murphy's five results at the event. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 ChampCar Stats detailing the 1922 AAA National Championship Trail standings. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Motorsports Hall of Fame of America page on Murphy. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Indy 500 Recaps providing some facts about the 1922 event (p.g. 1922). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ MotorSport detailing the results of the 1921 French Grand Prix. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Indianapolis Motor Speedway summarising the 1920 Indianapolis 500s. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Auto Racing in the Shadow of the Great War: Streamlined Specials and a New Generation of Drivers on American Speedways, 1915-1922 summarising the event and declaring it the first motor race to receive radio coverage (p.g. 383-385). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 26th May 1922 issue of The Border Cities Star reporting on ten entrants still yet to qualify for the event (p.g. 16). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Silverstone Museum noting Hawkes was the first driver to enter the Indianapolis 500 in a Bentley. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 28th May 1922 issue of The New York Times reporting on Kennerdell being selected to officiate the race (p.g. 22). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 22.14 31st May 1922 issue of The New York Times reporting on the race (p.g. 26). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 30th May 1922 issue of The Indianapolis Star reporting on the race's historic radio coverage (found on Newspapers.com, clipped by doctorindy500, p.g. 16. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Kevin Triplett's Racing History summarising the history of Indianapolis 500 radio broadcasts. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Indianapolis Motor Speedway summarising the history of Indianapolis 500 radio broadcasts and the formation of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Radio Network. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ History detailing how the Ray-Dundee boxing match was the first sporting event to receive live radio coverage. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 25th March 1922 issue of The Indianapolis Star reporting on the opening of the Hatfield broadcasting studio (WOH) (found on Newspapers.com, clipped by drewcareyradio, p.g. 10). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 8th July 1922 issue of Journal and Courier summarising the early history of Indianapolis radio stations, including the formation of WLK (found on Newspapers.com, clipped by mvpsew, p.g. 7). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 31st May 1922 issue of Warsaw Daily Times reporting on the race's radio coverage being heard in Indiana (p.g. 5). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 29th May 1929 issue of The Indianapolis News noting WKBF and WFBM promised to provide full live radio coverage of the 1929 Indianapolis 500 (found on Newspapers.com, clipped by doctorindy500, p.g. 12). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31st May 1922 issue of The Quebec Daily Telegraph reporting on the race and how three drivers achieved radio communication with their pit crews during the event (p.g. 2). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ IndyStar summarising Indianapolis Motor Speedway's dubious safety record. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Kenneth J. Parrotte explaining the various other trophies awarded to racers at the Indianapolis 500 (p.g. 1-5). Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Motorsport Memorial page for Murphy. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ ChampCar Stats detailing the 1924 AAA National Championship Trail standings. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Documenting Early Radio stating no surviving recordings exist between 1920 and 1922. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 National Archives stating President Wilson's Armistice Day is the oldest known surviving regular radio broadcast. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Archived Ngā Taonga noting most early-1920s sports airings were never recorded because of the impracticality involved. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Surviving coverage of the 1939 Indianapolis 500. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Johnson's Indy 500 summarising a list of recovered Indianapolis 500 radio broadcasts. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ r/INDYCAR discussing the oldest surviving Indianapolis 500 radio broadcasts. Retrieved 26th May '24

- ↑ Indianapolis Motor Speedway providing photographs of the race. Retrieved 26th May '24