Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

|status=<span style="color:red;">'''Lost'''</span> | |status=<span style="color:red;">'''Lost'''</span> | ||

}} | }} | ||

On 2nd July 1921, Georges Carpentier challenged Jack Dempsey for the latter's World Heavyweight Championship. Occurring at the Boyle's Thirty Acres with around 91,000 in | On 2nd July 1921, Georges Carpentier challenged Jack Dempsey for the latter's World Heavyweight Championship. Occurring at the Boyle's Thirty Acres with around 91,000 in attendance, Dempsey defeated the challenger after four rounds by KO. In one of boxing's biggest matches nicknamed "the fight of the century", the encounter was also historic for being the '''first world title boxing match to receive live radio coverage'''. | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Heading into the bout, Jack Dempsey had held the belt for near enough two years, after beating Jess Willard for it on 4th July 1919.<ref>[https://historythings.com/jack-dempsey-vs-jess-willard-1919-brutal-fight-history/ ''History Things'' detailing Dempsey's win over Willard.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="lawless">[https://web.archive.org/web/20080304091047/http://www.lawlessdecade.net/21-1.htm Archived ''Lawless Decade'' detailing Dempsey's career, including a solid report on his win over Carpentier and his post-boxing career.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="dempseyfame">[http:// | Heading into the bout, Jack Dempsey had held the belt for near enough two years, after beating Jess Willard for it on 4th July 1919.<ref>[https://historythings.com/jack-dempsey-vs-jess-willard-1919-brutal-fight-history/ ''History Things'' detailing Dempsey's win over Willard.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="lawless">[https://web.archive.org/web/20080304091047/http://www.lawlessdecade.net/21-1.htm Archived ''Lawless Decade'' detailing Dempsey's career, including a solid report on his win over Carpentier and his post-boxing career.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="dempseyfame">[http://ibhof.com/pages/about/inductees/oldtimer/dempsey.html ''International Boxing Hall of Fame'' summarising Dempsey's career.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="dempseyrecord">[https://boxrec.com/en/proboxer/9009 ''BoxRec'' detailing Dempsey's fights.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="city">[https://thefightcity.com/july-2-1921-dempsey-vs-carpentier-jack-dempsey-georges-carpentier-gene-tunney-tex-rickard/ ''The Fight City'' summarising the fight and detailing why most supported Carpentier over Dempsey.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref> The American had already made boxing coverage history, when his [[Jack Dempsey vs Billy Miske (lost radio report of boxing match; 1920)|victory over Billy Miske on 6th September 1920 was the first to receive radio coverage]], albeit in "fight returns" rather than a live play-by-play.<ref>[http://swmidirectory.org/Historic_Jack_Dempsey_vs_Billy_Miske_fight.php ''Southwest Michigan Directory'' noting the Dempsey-Miske fight received radio "fight returns".] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="dempseyrecord"/><ref name="dempseyfame"/> His last match was a KO victory over Bill Brennan on 14th December 1920.<ref name="dempseyrecord"/><ref name="dempseyfame"/> Meanwhile, Georges Carpentier was also a reigning world champion, the Frenchman having defeated Battling Levinsky for the World Light Heavyweight Championship on 12th October 1920.<ref name="carpentierrecord">[https://boxrec.com/en/box-pro/10604 ''BoxRec'' detailing Carpentier's fights.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="carpentierfame">[http://ibhof.com/pages/about/inductees/oldtimer/carpentier.html ''International Boxing Hall of Fame'' summarising the career of Carpentier.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="city"/> His final match up to that point, Carpentier would make the challenge for Dempsey's heavyweight crown, having won the IBU heavyweight title from Bombardier Billy Wells on 1st June 1913.<ref name="latimes">[https://latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-07-02-sp-1842-story.html ''The Los Angeles Times'' providing an account of the match round-by-round.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="carpentierrecord"/><ref name="carpentierfame"/><ref name="city"/> Tex Rickard and George Bernard Shaw saw money potential in the clash, and would increase intrigue over the bout by claiming Carpentier was at the time "the greatest boxer in the world."<ref name="guardian">[https://theguardian.com/sport/2021/jun/25/dempsey-v-carpentier-1921-start-of-modern-sports-broadcasting-heavyweight-boxing ''The Guardian'' detailing the radio broadcast and summarising the fight.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="lawless"/> This seemed an unusual tactic, considering Carpentier was not from America.<ref name="city"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="latimes"/> However, the promoters recognised that the crowd would actually be willing to support the Frenchman.<ref name="city"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="latimes"/> This was because whereas Carpentier fought for the French Army in the First World War, Dempsey did not enlist in the War, and faced numerous accusations of being a draft-dodger after a deferment he received was deemed undeserved by some during a court trial.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="latimes"/> | ||

The bout was also unique in that an arena was constructed to house it.<ref name="boyle">[https://finallyhomejc.com/guidetojerseycity/jersey-city-sports-boyles-thirty-acres-and-boxing-history ''Finally Home Jersey City'' detailing the creation of Boyle's Thirty Acres.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/> Rickard had taken out a loan of $250,000 to build the Boyle's Thirty Acres in Jersey City, after believing the match would draw a bigger crowd beyond what Madison Square Garden could accommodate.<ref name="boyle"/><ref name="latimes"/> The construction of the 91,000-capacity arena paid off, as the bout became the first to draw $1 million, topping out at $1,789,238.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="boyle"/><ref name="guardian"/> As expected, the media sided with Carpentier, praising his heroism during the War, bravery for facing a bigger man, and overall appearance.<ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Three months prior, on 11th April, a match [[Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)|pitting Johnny Ray and Johnny Dundee became the first to receive live radio play-by-play coverage]].<ref name="history">[https://earlyradiohistory.us/WJY.htm ''Early Radio History'' providing a detailed account on how the radio broadcast was achieved.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref> Julius Hopp, then-manager of Madison Square Garden concerts, saw the potential of providing radio coverage of the event to raise money for a veterans' charity operated by Anne Morgan.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> A proposal was accepted by Rickard, possibly in order to boost his relationship with Morgan's father, financier JP Morgan.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> After initially being rejected by amateur radio organisations due to the broadcast's supposed impracticality, Hopp received backing from the National Amateur Wireless Association, which was run under acting President Major J. Andrew White.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> White then approached RCA, estimating he needed about $15,000 to get the project running.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> Ultimately, RCA did provide a few engineers, including J. Owen Smith, but the company provided little financial backing.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> | The bout was also unique in that an arena was constructed to house it.<ref name="boyle">[https://finallyhomejc.com/guidetojerseycity/jersey-city-sports-boyles-thirty-acres-and-boxing-history ''Finally Home Jersey City'' detailing the creation of Boyle's Thirty Acres.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/> Rickard had taken out a loan of $250,000 to build the Boyle's Thirty Acres in Jersey City, after believing the match would draw a bigger crowd beyond what Madison Square Garden could accommodate.<ref name="boyle"/><ref name="latimes"/> The construction of the 91,000-capacity arena paid off, as the bout became the first to draw $1 million, topping out at $1,789,238.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="boyle"/><ref name="guardian"/> As expected, the media sided with Carpentier, praising his heroism during the War, bravery for facing a bigger man, and overall appearance.<ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Three months prior, on 11th April, a match [[Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)|pitting Johnny Ray and Johnny Dundee became the first to receive live radio play-by-play coverage]].<ref name="history">[https://earlyradiohistory.us/WJY.htm ''Early Radio History'' providing a detailed account on how the radio broadcast was achieved.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref> Julius Hopp, then-manager of Madison Square Garden concerts, saw the potential of providing radio coverage of the event to raise money for a veterans' charity operated by Anne Morgan.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> A proposal was accepted by Rickard, possibly in order to boost his relationship with Morgan's father, financier JP Morgan.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> After initially being rejected by amateur radio organisations due to the broadcast's supposed impracticality, Hopp received backing from the National Amateur Wireless Association, which was run under acting President Major J. Andrew White.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> White then approached RCA, estimating he needed about $15,000 to get the project running.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> Ultimately, RCA did provide a few engineers, including J. Owen Smith, but the company provided little financial backing.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> | ||

Still, David Sarnoff, its General Manager, contributed $1,500 | Still, David Sarnoff, its General Manager, contributed $1,500 to the project and promised further support.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> With partial assistance from RCA, a major campaign requesting assistance from radio enthusiasts proved a big success, with 58 theatres and halls being installed with aerials and receivers, in addition to other places like schools and fire stations.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> Further, Owen discovered that the Navy had produced a ship transmitter in Schenectady.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> Following discussions with Navy Club President and boxing and radio enthusiast Franklin D. Roosevelt, a deal with was made to have the broadcast "test" the transmitter in Hoboken, in exchange for a share of theatre revenue.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> Further ground was broken when Arthur Batcheller, the Radio Inspector of the Second District, managed to ensure the broadcast receiving transmitter authorisation.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> This makeshift station would be called WJY, which operated on a 1600 metre longwave wavelength to appease theatre goers.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> There were further roadblocks to overcome; initial plans to build a transmitter and aerial inside the Thirty Acres was blocked by Rickard promoter partner John Ringling, who also wanted the airing to not occur.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> The compromise was to construct the devices at a Lackawanna and Western Railway terminal in Hoboken.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> It was hoped to utilise a telephone line operated by AT&T to transmit the coverage.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> This was rejected by AT&T, forcing the ringside line to be transmitted to a telephone handset within the transmitter shack.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> | ||

==The Fight== | ==The Fight== | ||

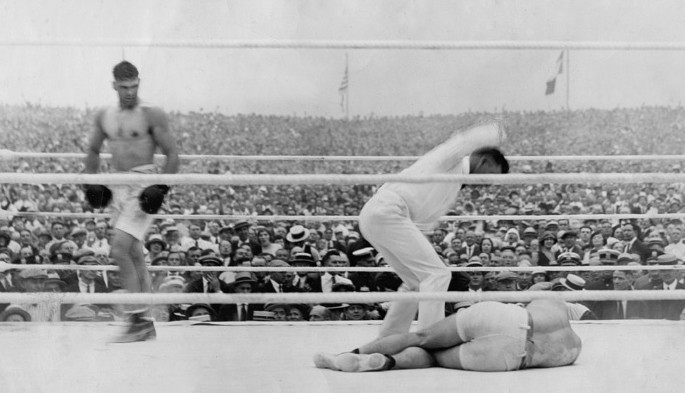

Despite claims that Smith was responsible for reading the ringside reports, it was actually White's responsibility.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> He gained some critical practice by providing play-by-play commentary to six preliminary matches.<ref name="history"/> All was now set for what the media regarded as the "Fight of the Century."<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/><ref name="lawless"/><ref name="city"/> The fight took place in front of 91,000 on 2nd July 1921.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/> Despite bigging up Carpentier to the media, Rickard was allegedly concerned regarding the Frenchman's prospects.<ref name="lawless"/> Aside from him being 20 pounds heavier than Carpentier, Dempsey also apparently was asked by the promoter not to end the fight prematurely.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="city"/> Dempsey seemingly agreed to these terms, as the fight went into four rounds.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Despite the champion being the more aggressive, Carpentier was able to counter, securing hooks to his foe's head and body. Dempsey | Despite claims that Smith was responsible for reading the ringside reports, it was actually White's responsibility.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> He gained some critical practice by providing play-by-play commentary to six preliminary matches.<ref name="history"/> All was now set for what the media regarded as the "Fight of the Century."<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/><ref name="lawless"/><ref name="city"/> The fight took place in front of 91,000 on 2nd July 1921.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/> Despite bigging up Carpentier to the media, Rickard was allegedly concerned regarding the Frenchman's prospects.<ref name="lawless"/> Aside from him being 20 pounds heavier than Carpentier, Dempsey also apparently was asked by the promoter not to end the fight prematurely.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="city"/> Dempsey seemingly agreed to these terms, as the fight went into four rounds.<ref name="lawless"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Despite the champion being the more aggressive, Carpentier was able to counter, securing hooks to his foe's head and body. Dempsey retaliated with a blow to the ribs and inflicting a cut on the Frenchman's nose. Carpentier was undeterred heading into the second round, including landing a left hook to the jaw and three more punches that almost secured a knockdown.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="lawless"/><ref name="carpentierfame"/> After regaining his composure however, Dempsey began to control proceedings from the third round onwards by landing several body blows.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="lawless"/><ref name="guardian"/> Carpentier's right thumb had also broken heading into the third round.<ref name="carpentierfame"/> In the fourth round, Carpentier made one last effort with by landing two right uppercuts. However, Dempsey landed a left-right combination that knocked down Carpentier.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="lawless"/> Carpentier did get up after nine, but 1:16 into the fourth round, a hard right body blow from Dempsey followed by a left hook secured another knockdown and this time the challenger was unable to make the count.<ref name="latimes"/><ref name="guardian"/><ref name="city"/><ref name="lawless"/><ref name="carpentierfame"/> | ||

Dempsey was paid $300,000, while Carpentier earned $200,000 for the match.<ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Dempsey held the world title for a few more years, eventually dropping it to Gene Tunney on 23rd September 1926.<ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="dempseyrecord"/> He lost a rematch to Tunney a year later, which would mark his final professional bout.<ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="dempseyrecord"/> He would later join the New York State Guard during the Second World War, receiving a honorable discharge from the Coast Guard Reserve in 1952.<ref name="lawless"/> Meanwhile, Carpentier made further radio history, when his [[Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)|victory over Ted "Kid" Lewis on 11th May 1922 became the first to receive live coverage in the United Kingdom]].<ref>[https://uk.news.yahoo.com/on-this-day--georges-carpentier-fights--kid--lewis-in-first-radio-covered-boxing-match-162414889.html ''Yahoo! News'' detailing the Carpenter-Lewis fight, which was the first to receive live radio coverage.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="carpentierfame"/><ref name="carpentierrecord"/> He dropped his titles to Battling Siki on 24th September 1922 | Dempsey was paid $300,000, while Carpentier earned $200,000 for the match.<ref name="city"/><ref name="latimes"/> Dempsey held the world title for a few more years, eventually dropping it to Gene Tunney on 23rd September 1926.<ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="dempseyrecord"/> He lost a rematch to Tunney a year later, which would mark his final professional bout.<ref name="dempseyfame"/><ref name="dempseyrecord"/> He would later join the New York State Guard during the Second World War, receiving a honorable discharge from the Coast Guard Reserve in 1952.<ref name="lawless"/> Meanwhile, Carpentier made further radio history, when his [[Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)|victory over Ted "Kid" Lewis on 11th May 1922 became the first to receive live coverage in the United Kingdom]].<ref>[https://uk.news.yahoo.com/on-this-day--georges-carpentier-fights--kid--lewis-in-first-radio-covered-boxing-match-162414889.html ''Yahoo! News'' detailing the Carpenter-Lewis fight, which was the first to receive live radio coverage.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="carpentierfame"/><ref name="carpentierrecord"/> He dropped his titles to Battling Siki on 24th September 1922 but regained the IBU Heavyweight title by beating Joe Beckett on 1st October 1923.<ref name="carpentierfame"/><ref name="carpentierrecord"/> He retired following a win over Rocco Stramaglia on 15th September 1926.<ref name="carpentierrecord"/><ref name="carpentierfame"/> Finally, White completed a four-hour live broadcast of the match, enduring intense heat.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> He was concerned that the broadcast had prematurely ended when he initially received no response from the line regarding the results of his work.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> Ultimately, he was informed the entire coverage was aired, receiving critical acclaim.<ref name="history"/><ref name="guardian"/> While its extent was overestimated, as most listeners were radio enthusiasts, it has since been described as the beginning of modern sports broadcasting.<ref name="guardian"/><ref name="history"/> | ||

==Availability== | ==Availability== | ||

Ultimately, the radio coverage was transmitted live during a period | Ultimately, the radio coverage was transmitted live during a period when radio recordings seldom happened.<ref name="nga">[https://ngataonga.org.nz/blog/uncategorized/our-oldest-recorded-sports-broadcast-the-all-blacks-vs-the-british-lions-june-21-1930/ ''Ngā Taonga'' noting most early-1920s airings were never recorded.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="time">[https://old-time.com/mcleod/mcleod3.html ''Old-Time'' detailing the oldest surviving radio broadcasts and noting no authenticated examples exist between 1920-1922.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="ben">[https://benbeck.co.uk/firsts/1_Technology/sound1t.htm ''Benjamin S. Beck'' detailing various examples claiming to be the earliest surviving radio broadcast.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref><ref name="national">[https://archives.gov/press/press-releases/2005/nr05-60.html ''National Archives'' stating the oldest surviving radio broadcast is Woodrow Wilson's Armistice Day Speech from 1923.] Retrieved 27th Dec '22</ref> This was especially the case for outside sporting broadcasts, as the few viable means of recording them back then were impractical, for instance transporting heavy acetate or lacquer discs.<ref name="nga"/> Based on various research regarding the oldest surviving radio recordings, none that have been authenticated exist between 1920-1922, with the oldest recording according to the National Archives being Woodrow Wilson's Armistice Day Speech in 1923.<ref name="ben"/><ref name="national"/><ref name="time"/> Thus, the coverage is most likely forever missing. Nevertheless, the match itself was also filmed, and it can be publicly accessed. | ||

==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:46, 31 January 2023

On 2nd July 1921, Georges Carpentier challenged Jack Dempsey for the latter's World Heavyweight Championship. Occurring at the Boyle's Thirty Acres with around 91,000 in attendance, Dempsey defeated the challenger after four rounds by KO. In one of boxing's biggest matches nicknamed "the fight of the century", the encounter was also historic for being the first world title boxing match to receive live radio coverage.

Background

Heading into the bout, Jack Dempsey had held the belt for near enough two years, after beating Jess Willard for it on 4th July 1919.[1][2][3][4][5] The American had already made boxing coverage history, when his victory over Billy Miske on 6th September 1920 was the first to receive radio coverage, albeit in "fight returns" rather than a live play-by-play.[6][4][3] His last match was a KO victory over Bill Brennan on 14th December 1920.[4][3] Meanwhile, Georges Carpentier was also a reigning world champion, the Frenchman having defeated Battling Levinsky for the World Light Heavyweight Championship on 12th October 1920.[7][8][5] His final match up to that point, Carpentier would make the challenge for Dempsey's heavyweight crown, having won the IBU heavyweight title from Bombardier Billy Wells on 1st June 1913.[9][7][8][5] Tex Rickard and George Bernard Shaw saw money potential in the clash, and would increase intrigue over the bout by claiming Carpentier was at the time "the greatest boxer in the world."[10][2] This seemed an unusual tactic, considering Carpentier was not from America.[5][10][9] However, the promoters recognised that the crowd would actually be willing to support the Frenchman.[5][10][9] This was because whereas Carpentier fought for the French Army in the First World War, Dempsey did not enlist in the War, and faced numerous accusations of being a draft-dodger after a deferment he received was deemed undeserved by some during a court trial.[2][5][10][9]

The bout was also unique in that an arena was constructed to house it.[11][9][5] Rickard had taken out a loan of $250,000 to build the Boyle's Thirty Acres in Jersey City, after believing the match would draw a bigger crowd beyond what Madison Square Garden could accommodate.[11][9] The construction of the 91,000-capacity arena paid off, as the bout became the first to draw $1 million, topping out at $1,789,238.[9][3][11][10] As expected, the media sided with Carpentier, praising his heroism during the War, bravery for facing a bigger man, and overall appearance.[5][9] Three months prior, on 11th April, a match pitting Johnny Ray and Johnny Dundee became the first to receive live radio play-by-play coverage.[12] Julius Hopp, then-manager of Madison Square Garden concerts, saw the potential of providing radio coverage of the event to raise money for a veterans' charity operated by Anne Morgan.[10][12] A proposal was accepted by Rickard, possibly in order to boost his relationship with Morgan's father, financier JP Morgan.[10][12] After initially being rejected by amateur radio organisations due to the broadcast's supposed impracticality, Hopp received backing from the National Amateur Wireless Association, which was run under acting President Major J. Andrew White.[12][10] White then approached RCA, estimating he needed about $15,000 to get the project running.[10][12] Ultimately, RCA did provide a few engineers, including J. Owen Smith, but the company provided little financial backing.[12][10]

Still, David Sarnoff, its General Manager, contributed $1,500 to the project and promised further support.[12][10] With partial assistance from RCA, a major campaign requesting assistance from radio enthusiasts proved a big success, with 58 theatres and halls being installed with aerials and receivers, in addition to other places like schools and fire stations.[12][10] Further, Owen discovered that the Navy had produced a ship transmitter in Schenectady.[12][10] Following discussions with Navy Club President and boxing and radio enthusiast Franklin D. Roosevelt, a deal with was made to have the broadcast "test" the transmitter in Hoboken, in exchange for a share of theatre revenue.[12][10] Further ground was broken when Arthur Batcheller, the Radio Inspector of the Second District, managed to ensure the broadcast receiving transmitter authorisation.[12][10] This makeshift station would be called WJY, which operated on a 1600 metre longwave wavelength to appease theatre goers.[12][10] There were further roadblocks to overcome; initial plans to build a transmitter and aerial inside the Thirty Acres was blocked by Rickard promoter partner John Ringling, who also wanted the airing to not occur.[12][10] The compromise was to construct the devices at a Lackawanna and Western Railway terminal in Hoboken.[12][10] It was hoped to utilise a telephone line operated by AT&T to transmit the coverage.[12][10] This was rejected by AT&T, forcing the ringside line to be transmitted to a telephone handset within the transmitter shack.[12][10]

The Fight

Despite claims that Smith was responsible for reading the ringside reports, it was actually White's responsibility.[12][10] He gained some critical practice by providing play-by-play commentary to six preliminary matches.[12] All was now set for what the media regarded as the "Fight of the Century."[10][12][2][5] The fight took place in front of 91,000 on 2nd July 1921.[2][9][5] Despite bigging up Carpentier to the media, Rickard was allegedly concerned regarding the Frenchman's prospects.[2] Aside from him being 20 pounds heavier than Carpentier, Dempsey also apparently was asked by the promoter not to end the fight prematurely.[2][5] Dempsey seemingly agreed to these terms, as the fight went into four rounds.[2][10][5][9] Despite the champion being the more aggressive, Carpentier was able to counter, securing hooks to his foe's head and body. Dempsey retaliated with a blow to the ribs and inflicting a cut on the Frenchman's nose. Carpentier was undeterred heading into the second round, including landing a left hook to the jaw and three more punches that almost secured a knockdown.[9][5][2][8] After regaining his composure however, Dempsey began to control proceedings from the third round onwards by landing several body blows.[9][5][2][10] Carpentier's right thumb had also broken heading into the third round.[8] In the fourth round, Carpentier made one last effort with by landing two right uppercuts. However, Dempsey landed a left-right combination that knocked down Carpentier.[9][10][5][2] Carpentier did get up after nine, but 1:16 into the fourth round, a hard right body blow from Dempsey followed by a left hook secured another knockdown and this time the challenger was unable to make the count.[9][10][5][2][8]

Dempsey was paid $300,000, while Carpentier earned $200,000 for the match.[5][9] Dempsey held the world title for a few more years, eventually dropping it to Gene Tunney on 23rd September 1926.[3][4] He lost a rematch to Tunney a year later, which would mark his final professional bout.[3][4] He would later join the New York State Guard during the Second World War, receiving a honorable discharge from the Coast Guard Reserve in 1952.[2] Meanwhile, Carpentier made further radio history, when his victory over Ted "Kid" Lewis on 11th May 1922 became the first to receive live coverage in the United Kingdom.[13][8][7] He dropped his titles to Battling Siki on 24th September 1922 but regained the IBU Heavyweight title by beating Joe Beckett on 1st October 1923.[8][7] He retired following a win over Rocco Stramaglia on 15th September 1926.[7][8] Finally, White completed a four-hour live broadcast of the match, enduring intense heat.[12][10] He was concerned that the broadcast had prematurely ended when he initially received no response from the line regarding the results of his work.[10][12] Ultimately, he was informed the entire coverage was aired, receiving critical acclaim.[12][10] While its extent was overestimated, as most listeners were radio enthusiasts, it has since been described as the beginning of modern sports broadcasting.[10][12]

Availability

Ultimately, the radio coverage was transmitted live during a period when radio recordings seldom happened.[14][15][16][17] This was especially the case for outside sporting broadcasts, as the few viable means of recording them back then were impractical, for instance transporting heavy acetate or lacquer discs.[14] Based on various research regarding the oldest surviving radio recordings, none that have been authenticated exist between 1920-1922, with the oldest recording according to the National Archives being Woodrow Wilson's Armistice Day Speech in 1923.[16][17][15] Thus, the coverage is most likely forever missing. Nevertheless, the match itself was also filmed, and it can be publicly accessed.

Gallery

Video

See Also

- Bill Lewis vs Freddie Baxter and Archie Sexton vs Laurie Raiteri (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1933)

- Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- England vs Ireland (lost television coverage of boxing matches; 1937)

- Exhibition Boxing Bouts (lost early television coverage of boxing matches; 1931-1932)

- Georges Carpentier vs Ted "Kid" Lewis (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1922)

- Heavyweight Champ (lost SEGA arcade boxing game; 1976)

- Jack Dempsey vs Billy Miske (lost radio report of boxing match; 1920)

- Jo-Ann Hagen vs Barbara Buttrick (lost radio and television coverage of boxing match; 1954)

- Johnny Ray vs Johnny Dundee (lost radio coverage of boxing match; 1921)

- Leonard-Cushing Fight (partially found early boxing film; 1894)

- Rocky (lost deleted scenes of boxing drama film; 1976)

- Uncle Slam and Uncle Slam Vice Squad (lost iOS presidential boxing games; 2011)

References

- ↑ History Things detailing Dempsey's win over Willard. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Archived Lawless Decade detailing Dempsey's career, including a solid report on his win over Carpentier and his post-boxing career. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 International Boxing Hall of Fame summarising Dempsey's career. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 BoxRec detailing Dempsey's fights. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 The Fight City summarising the fight and detailing why most supported Carpentier over Dempsey. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ Southwest Michigan Directory noting the Dempsey-Miske fight received radio "fight returns". Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 BoxRec detailing Carpentier's fights. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 International Boxing Hall of Fame summarising the career of Carpentier. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 The Los Angeles Times providing an account of the match round-by-round. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 10.19 10.20 10.21 10.22 10.23 10.24 10.25 10.26 10.27 10.28 10.29 The Guardian detailing the radio broadcast and summarising the fight. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Finally Home Jersey City detailing the creation of Boyle's Thirty Acres. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 Early Radio History providing a detailed account on how the radio broadcast was achieved. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ Yahoo! News detailing the Carpenter-Lewis fight, which was the first to receive live radio coverage. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ngā Taonga noting most early-1920s airings were never recorded. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Old-Time detailing the oldest surviving radio broadcasts and noting no authenticated examples exist between 1920-1922. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Benjamin S. Beck detailing various examples claiming to be the earliest surviving radio broadcast. Retrieved 27th Dec '22

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 National Archives stating the oldest surviving radio broadcast is Woodrow Wilson's Armistice Day Speech from 1923. Retrieved 27th Dec '22